You have more options than they will ever tell you you have

Today we're going to have a discussion about living with a chronic illness and the need to advocate for yourself in the face of indifference to your pain or refusal of treatment from doctors or your insurance company.

After two long years of inconclusive tests, and ten years of delayed diagnosis, Lauren Cohn-Frankel was recently diagnosed with a rare autoimmune illness called eosinophilic fasciitis. Their specialist has seen significant improvement in cases like this with a specialized treatment, but as you will not be surprised to hear, Blue Shield of California are refusing to pay for it.

"It’s incredibly expensive, but it has the capacity to halt or reverse the disease process and improve my pain, disability, and overall quality of life," Lauren told me. "But my insurance refuses to follow their own off-label criteria to approve the drug. In less than 72 hours they rejected both my doctor's original prior authorization request and her appeal. I figure at some point I was put on a high utilization list because Blue Shield has denied more than 20 claims for in-network services in 2023 alone. Our plan is the most expensive Silver plan in our county, with premiums going up 50% two years in a row. But it’s also the only one whose networks haven’t been stripped of the specialists we need at the nearest university hospital. I frequently have to spend more hours in a day fighting for us to get the care we pay for than I spend doing my actual job."

"I refuse to let myself be one of the people who is intimidated into just giving up by how difficult they make it, but I know that as a sick person even having the time and energy to advocate for myself is a rare privilege."

Read our talk below.

If you missed my chat with David Roth the other day it was delightful. Delightful! We talked about media business ghouls and many other things.

"Popular Science has been around like 150 years. Jezebel has been around like fifteen years. When you buy sites like that, with an archive of old stories that people are gonna find and that show up in search results, and in many cases are very good and very useful, that in itself is worth something. You'll make money just having that. They're not gonna make a ton of money, but you're not spending any new money on it either. Why would you destroy the value that's latent in that, just so that you can ride a website all the way down into the ground? Until it is completely indistinguishable from the shit that we were talking about where it's “Calista Flockhart today will depress you”? Every website has to be that? Just because it's cheaper to do?"

I also got pissed off about Decorum and The Rules the other day in this piece for paid subscribers.

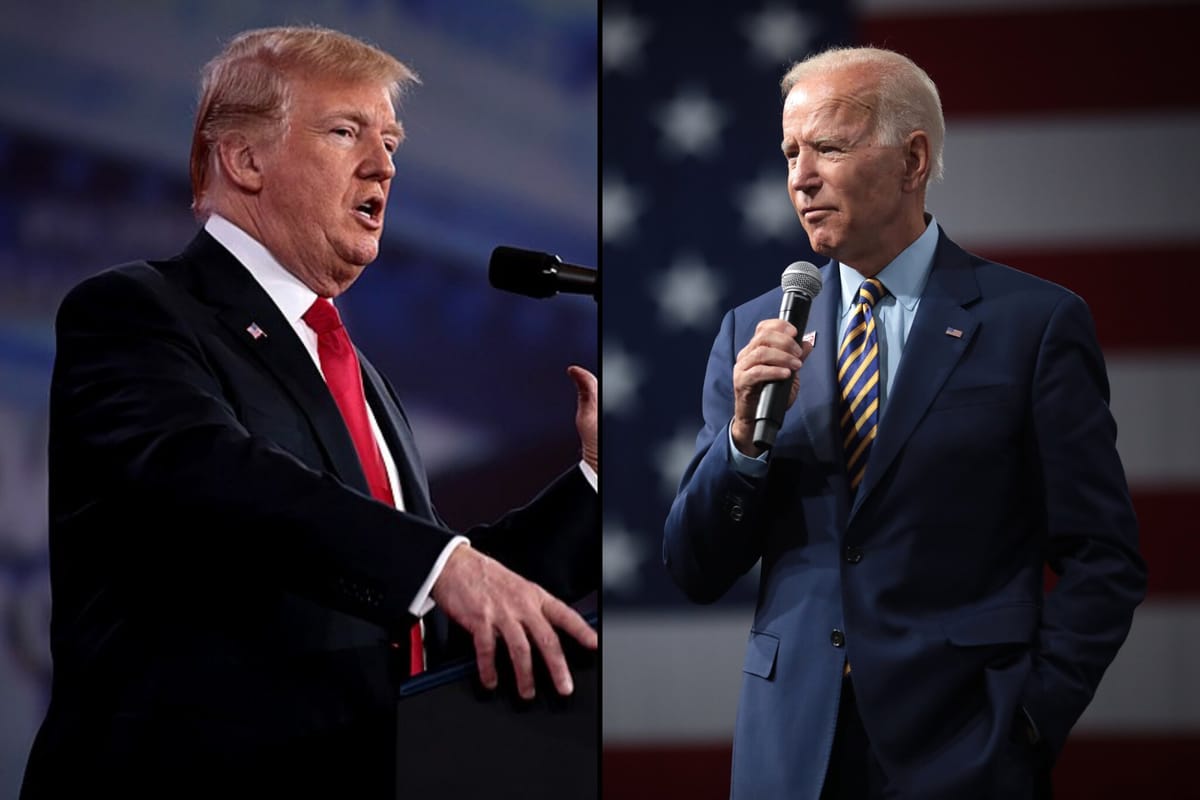

The thing I want to know is is it that Trump is so much more savvy a politician and understander of the processes of government to be able to get what he wants – whatever frightening thing he's supposed to be about to do – or are the Democrats for all their supposed brain power just content to slow roll and bullshit us saying they really would like to help but it all takes time you see? Uhh ... the parliamentarian won't let us.

Is this an existential crisis for democracy or not? And you’re pointing to Some Guy as the reason you can’t wield power? Some rule?

Here's a nice discount if you want to read that one.

If you've been watching Fargo season 5 – and you should be – you might appreciate this old piece from the Welcome to Hell World book about sin-eaters.

The essence of Munslow’s duties was to perform a sort of shamanistic ritual in which a piece of bread and a bowl of ale were passed over the remains of the recently deceased. The sins of the deceased were – as any idiot will obviously understand – thereby subsumed into the meal and the sad bastard would dine on them taking the sins on as his own and ensuring that the dead would pass unmolested through the gates of Heaven.

Sin-eaters were commonly itinerant and destitute types traveling here and there until they were called upon in haste. Who but the most desperate would agree to such a one-sided metaphysical bargain in the first place? They were paid very little for the gruesome task and furthermore shunned as foul pariahs for their trouble when it was done. Each bite of bread and each sip of ale further curdled their own load-bearing souls.

"Bodies pile up" (?)

Do major news organizations usually use that kind of language about mass death?

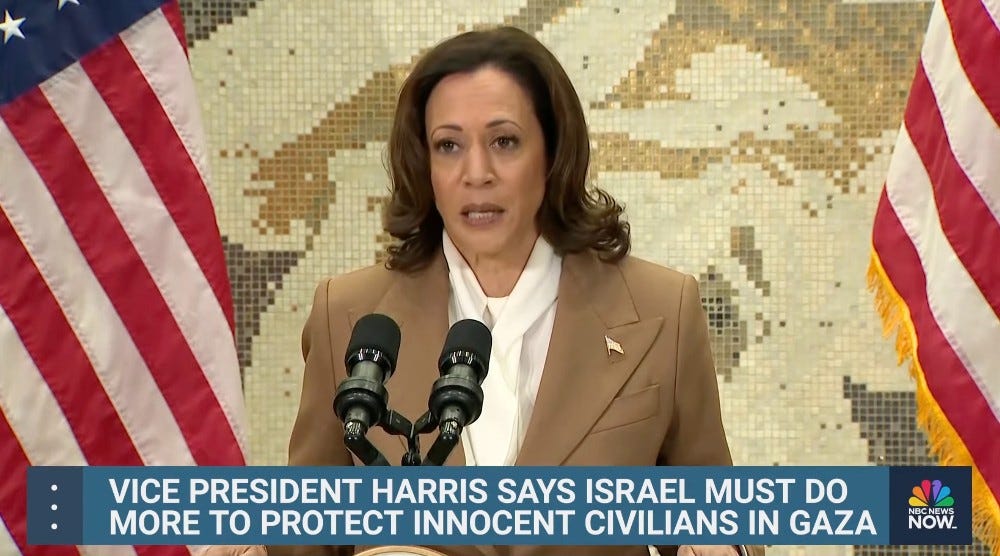

I cannot believe we are still allowing this massacre to go on hour by hour day by day. Doing nothing to stop it but saying pretty please do the bombings more ethically. Jack Mirkinson on Discourse Blog was good on the matter today.

I feel crazy for having to spell this out, but here goes: if you say that you want a country to stop killing so many civilians, and at the same time you are sending that country tens of thousands of weapons that a) are usually used in “non-urban” regions rather than, say, an area that is three times as densely populated as Los Angeles, and that b) you 1000 percent know are being used to massacre civilians, because, among other things, you keep talking about how many civilians are dying, you do not actually want that country to stop killing so many civilians. You are helping the killing continue. Obviously.

Or, as one anonymous administration official told NBC News last week, “Once pictures started coming out of the rubble of 5,000 dead, 10,000 dead … we all know the tools they used to kill them.” In case you think there’s any ambiguity there, NBC News added that the official was “referring to the U.S.-made weapons supplied to Israel.”

You have had you're fucking bloody revenge fifty fold by now. How many more must be killed before someone puts a stop to this?

A Palestinian girl asks is 'this a dream or reality' as medics treat her wounds after Israeli forces bombarded her house in southern Gaza's Rafah⤵️ pic.twitter.com/nLnAyaGHwC

— Al Jazeera English (@AJEnglish) December 3, 2023

Alright here's me and Cohn-Frankel talking about pain and health and health and pain.

Oh wait one more thing! The next edition of the Top 5 Songs series I've been doing is going to be about The Cure. If you're a journalist or a musician friend of some modest renown and would like to chime in let me know. (Read the ones about Elliott Smith, R.E.M., and Weezer if you missed them.)

I’m sorry you're going through a shitty time but I appreciate you sharing your story. There are obviously lots of bad parts of dealing with a chronic illness, but one thing that kind of gets overlooked is how often you have to explain your whole deal to people over and over. Whether it's yet another doctor, or a friend, or a reporter as the case may be. Is that something that gets exhausting?

It really depends on how the person is listening. If they're actually interested in believing what I have to say and empathetic then I think it's okay. If it's more like a challenge or a cross examination, then yeah, it gets exhausting. That happens a lot with rare freaky illnesses like this.

Well I'm a complete asshole who doesn't believe what you're saying so I just want to get that out of the way up front.

Haha.

So what is the condition that you're dealing with?

It's called eosinophilic fasciitis. Basically what happens is the fascia, the layer of connective tissue between your skin and your muscle, or your muscle and your fat, gets inflamed. And then over time it gets inflamed in an autoimmune way, like, your cells are attacking themselves. And then over time, especially if it's not treated when it's in the initial inflammatory state, it gets hardened. So instead of this stretchy mobile tissue that slides over itself to keep everything moving, it gets scarred and sticks to itself, sticks to your muscle, sticks to your fat.

Is it especially painful?

Yes. In the early stages of it you get what's called lymphedema, which is sort of like swelling in your lymphatic system. So your legs or your arms will be really swollen. Kind of like people have after breast cancer treatment sometimes. It will be hard to bend your arm or bend your leg. And that's painful. And then in the later stages, like what I have, it's sort of like wearing a corset under your skin.

Oh god.

Yeah, it sucks. And it's really obvious if you take five minutes to touch my body, to examine me, you can tell it's not normal tissue.

When did this first start happening?

They're not sure what causes it. There's a bunch of different scenarios that can cause it. One of them is physical trauma. I was in an accident in 2013. It was a fall. A porch collapsed in a building that I was thinking about renting.

A porch collapse?

Yeah. Even though I fell two stories, I wasn't badly injured. I had a broken toe and some bruises and cuts and stuff like that. But about a week after the fall, I started getting swelling in my legs. I went to the doctor, I had Kaiser at the time, and they determined it wasn't something acute like compartment syndrome. And they were just like, yep, I don't know what it is! I guess you're just 35 and fat and these kinds of things happen! It's not something life threatening. We don't really know why this is happening.

As a fat person, there's a lot of dismissal and neglect in medical care. And a lot of symptoms can be attributed to that when they may not be. But that was sort of the answer.

So the lymphedema stayed, and it stayed that way for about two years. I was getting this kind of massage treatment that helps to encourage your lymph nodes to take up more fluid and move it around your body. So that helped with that and that went away. But over that period my health was just getting worse and worse and worse. I was collecting more and more diagnoses. Some of the more standard thirties and forties ones like high blood pressure and diabetes.

Being heavier, is that something that you feel like doctors use to dismiss you?

Absolutely. Well first of all, they don't like to touch you.

Really?

Yeah, and that happens with a lot of marginalized groups. I think I've read that the average exam in the ER if you're black is less time than if you're white, or if you're trans for example. So, yeah, they don't like to touch your body… I don't want to project and say that l’m seen as icky or something, but there is a feeling with a lot of doctors... With this thing I have, in the initial stages it's not something that you can see just looking at me, although now it is. But it was something that you could feel if you palpate my skin. Asking doctors to do that, they were always just really, really hesitant. A couple times I had to take their hands and place it on my body and push it around.

I guess it matters for what we’re talking about here, but are you trans yourself?

Yes. I’m non-binary.

So you've got a couple different things working against you in terms of doctors taking you seriously.

Yes, and systems like Kaiser where there's a lot of really standardized rules of how you practice, and what tests you do, and under what conditions you can do those tests, it's just really not set up to catch things that are not super obvious and super diagnosable with something like a blood test. Something that's like a yes or no answer.

After leaving Kaiser, my health started improving, but I still had a lot of these sort of amorphous symptoms like joint pain, muscle pain, restricted movement, fatigue.

What led you to leave Kaiser?

That was about two years after the accident, and it was just becoming really clear that there was something wrong with me. It turns out quite a few things. I wasn't getting satisfactory answers, and I wasn't getting a lot of curiosity about that from the doctors that I saw there. I wasn't really getting an attitude of like, yes, you don't feel well, and it's not because of something you were doing, it's because of something that's happening in your body and we're going to find out what it is. That attitude was really not there.

You think they were sort of blaming you for your own pain? I write about that sort of thing a lot. I’ve had a lot of recurring injuries over my life. I’ve often had to go see the pain clinic. I wrote a piece like this once, it's like they always want to make sure whether or not you have your pain coming to you.

Yes, exactly.

I've had abdominal injuries and back injuries from exercise and things like that. And every time I have to prove once again that I'm not a drug seeker.

Or faking. And that's actually also what was happening at the time. 2013 was the beginning of the understanding that America has what we now call the opioid epidemic. Or at least like the first few years of that. And so there was this total reversal from, like, yes, chronic pain is a thing that people have, and that we treat, and that we validate, and sometimes maybe validate a little too much, to, like, no, you get PT and that's it. If you’re lucky.

When you have a diagnosis that is easily identifiable that causes pain, people treat you as if your pain is valid and seek to help. But when you either don't have that diagnosis yet, which happens in a lot of rheumatological illnesses because so many of them are diagnosed based on symptoms and some blood work, and that kind of stuff evolves over the years, it has to get bad enough basically for it to be recognizable. And then if on top of that you have a lot of reasons why doctors will be skeptical, then it can be quite a while before you have something that gets validated as a reason to cause your pain that is not your fault.

What do you do for a living?

I'm a psychotherapist. I work with a lot of queer and trans people. I do work with chronically ill and disabled people, people with trauma and PTSD.

That's got to be heavy work.

Yeah, but I love it.

That’s great. I've done various types of therapy over the years, and it's really just a matter of, similar to a doctor, finding someone who seems like they give a shit about you.

So you left Kaiser?

Then I started getting better, more concerned, more empathetic, and more interested in me doctors. But I would see a doctor for a year, year and a half, then they would leave the practice, sometimes with no notice, and then I would have to find a new one. And that happened four or five times in a row. I was making some progress with figuring some of this stuff out, of what was going on. My health picture is really complex, so it's not just one thing. This is just the weirdest and latest part of it. The other things are more garden variety. The disruption of those relationships, and then it being hard to find a doctor who I feel comfortable with, and then having to kind of start all over, that was really hard.

But then about six years ago I found the PCP that I still have now, and she is brilliant, and very well connected with referrals at the nearest university teaching hospital which is UCSF. She specializes in treating complex chronically ill patients. So she has been a huge part of the improvement in my health in finding specialists to figure out what was going on, who are themselves empathetic and interested and very competent, especially in seeing things that are out of the box in some way.

That's another thing I’m always going on about. When we're told to see our doctor. Who's my doctor again? Do I have one? It's often people are seeing the nurse practitioner instead or whatever. And then to have them cycling in and out of your care, probably for stupid for-profit health care reasons, right?

Exactly. Relating to that, I think a lot of them were younger doctors, and so they would join a practice in their first few years, and then they would get enough experience or whatever that they'd be able to open their own practice, or something would change about the insurance reimbursement and so they’d leave. Even pre-Covid, and especially now, there aren’t a lot of medical systems that are sustainable for doctors to work in. To be paid well for their time and their expertise and their student loans, and to be given the time to actually spend with patients and on notes and on consultations. I think that's part of it too. This wonderful doctor that I've had for six years just took a very abrupt extended leave, from what I suspect is burnout, because her medical system was bought by Amazon a couple of years ago.

Amazon? Jesus Christ.

Yeah! The amount of time they can spend with us has gone down. The amount of turning time they have allotted is like nothing. And in a case like mine, a lot of it is work on the back end.

Obviously we hate this system that we get our health care under. It's easy to say the doctor doesn't give a shit or whatever. But then, you know, a lot of times they really are being pinched by Amazon or… I'm not trying to completely let doctors off the hook for their role, but in a lot of ways they're being fucked over too.

I think that's true. And I didn't really understand that way back in the beginning. I really didn't understand how they are not getting what they need to be what we need either.

Nobody is happy in this system except for the fucking assholes at the top who are siphoning off all the money, right?

So who is the insurance that's fucking you know?

Blue Shield of California. The nonprofit I work for is small, so they don't have benefits, so I have a Covered California plan that I pay for here in Sonoma County. It’s $471 a month and it's going up to $660 next year. And that's with all of the available subsidies, all of the cost share and tax credits for a Silver 94 plan. The other Silver 94 plans in my county, in San Francisco and Alameda counties, are somewhere between zero and a hundred dollars, but mine is the only one that has the network that covers UCSF in my county. If I had a different plan that was cheaper, or cost me nothing, I wouldn't be able to see the doctors that I really need to see without approval from the plan for every single one. Like eight doctors in UCSF. And I wouldn't be able to see my PCP at all. I'd have to find a new PCP

I assume working for a nonprofit you're not exactly making big bucks.

Exactly. My life is stable, but no, I'm not rich. I'm not even upper middle class.

I live in Massachusetts, you're in California, these are supposedly the good states. I do think we have it a little bit better than many other states, but even still it's just so frustrating that that everything is a whole fucking thing. To just see a doctor, to just figure out what's going on.

Yeah it’s really disheartening.

So what happened next?

I knew something was wrong with me, but I didn't realize that the way my body felt was not normal until I started dating again, and like having friends and people who were around my body, where I could be like, is this how this is supposed to feel? You've dated other fat people, is this what fat people's bellies are supposed to feel like? They were like, no! And then I had a naturopathic doctor, an acupuncturist, who saw me every week, and who was working on these painful constricted muscle and tissue areas. After a while he said I think I know what this is. And I think this could be one of two things, one of which was EF. But he was not in a position to do any diagnosing of that. He said, I'm gonna talk to your PCP. And I think you need a biopsy to figure this out.

So that started the actual movement on this thing. It was actually a two year process from there to getting the diagnosis this October, because, ironically, I have another autoimmune disease, a more common one, psoriatic arthritis, and that's being treated with immunosuppressants. And the theory that my specialist has now, is that the immunosuppressants are partially working on the other thing. And so they're reducing the inflammation I have overall in my body, which actually made it harder to diagnose, because that wasn't measurable in the like eight biopsies that we took over two years.

We did a lot of MRIs too, and finally we did an MRI of my extremities, and that's where we got definitive proof that they can see the constriction and hardening basically under the skin.

I've shown these symptoms to probably five or six different doctors, five or six different rheumatologists, two PCPs over the years, and my current specialist was the first person who, when I got into her office and she examined me, she was like, I am 95% sure that I know what this is. My current autoimmune dermatologist.

She said we need to definitively determine this, so we're going to do some biopsies, we're going to do some MRIs. And there were these different stages of getting a test, hoping it would show something, it not showing something, being disappointed, being scared that we weren't going to be able to get the information that we needed to treat this. From the beginning she was saying your case is really advanced because you've had so many years of having this not diagnosed and it got missed when it first showed up, that you've got just a lot of permanent damage from it. But she said there is this one treatment that I've had success with and that there's been other case studies that have had success with treating somebody at your stage of this, and it's this treatment IVIG, or intravenous immunoglobulin.

That took two years. And then finally, we got this definitive information, and that's when, you know, she was like, okay, let's start getting insurance approval for this, and let's start you in January. And this is really, just to talk about like the emotional part of it, this is a really exciting stage. You said in your email I'm sorry that you're going through this health scare or something like that. And that's really not the feeling. The feeling is like there's been something wrong with me, I've known that there's something wrong with me, the last couple of years I've had ideas about what it is from doing my own research, so it's like validation. It's like relief.

Oh, sure. It's almost like you can see the oasis just up ahead that you've been walking toward through the desert.

Exactly. And this thing affects so much of my body. It's my upper arms, upper legs, lower legs, my back, my sides, my belly. I don't even know what my body would feel like if all of that like constricted hardened tissue was gone or even half of it was gone. It would be completely life changing.

You get so used to living in pain sometimes that you might give up on the idea that it's possible that you might not have to...

Yeah. And I feel better now, even with this stuff, even with this not being treated, I feel better now than I have in, you know, seven or eight years because all the other stuff has been treated and has been discovered and treated. So this is sort of like the last piece of it that is a really big piece.

But of course the insurance is saying they don't want to pay for it.

So here's the thing, it's a very rare disease to begin with. There's only, I think, 300 cases in medical literature of the disease itself.... I have been on prednisone, have been on and off like three different immunomodulating drugs, five different biologic immunosuppressive drugs. The one that I'm on now is the first thing that's worked for the autoimmune disease, and the other ones have not. So I've tried and failed all of the cheaper remedies for this that don't really tend to work in advanced cases anyway [that the insurance company is insisting I try instead of the more expensive one.]

There's not enough people that have this to do a large scale study that would result in this treatment being FDA-approved for this disease. It’s an off-label treatment.

But your specialist thinks that it will help.

And there is peer-reviewed medical literature that backs that up.

Is your doctor frustrated? What are they saying about them refusing this?

I've talked to the person in our office who does the authorizations and she was basically like, every insurance is different. What every insurance will allow and won't allow is different. Their requirements are different. So I've had to do, as always, I've had to do a lot of the work myself in finding out what my insurance requirements were to potentially approve this. Like what their requirements are to approve a drug off-label.

So as far as you can tell, it should qualify?

Should, but that doesn't mean that they have to approve it. The first prior authorization in which she sent all my notes, sent the reasoning for why she was prescribing this, sent my history, my lab results, they said no. And then she filed an appeal and wrote a more lengthy submission. And they said no again. Both refusals within 72 hours. They said that there are no studies that back this up, which is not true. They cited two studies that say that the typical treatments are just a list of drugs, some of which I have already tried that have not worked on me.

So what has to happen now is I have to file a grievance to reopen the appeal with more information. Another university medical center, Stanford, actually has a clinic for autoimmune skin diseases. It's one of five in the country. And I'm going to see them next week and hopefully get supporting letters of medical necessity from them and discuss with them what studies we should include in the next appeal.

I've read as many studies as I can find on this treatment for eosinophilic fasciitis. I've bookmarked all those studies. If the insurance denies the second appeal, there's a stage after that where the doctor could request what's called a peer to peer review, where she gets on the phone with the doctor from my insurance and explains, they have a conversation about it, and she tries to basically convince them that they should allow this. And that was the thing that my insurance did not tell me that I had a right to. I had to find that out from, you know, like Reddit, basically.

You're lucky, so to speak, in that you have a doctor that is willing to do all of this.

Is willing to go to bat. She's extremely busy. The fact that she has a staff that can do this. The fact that she's willing to do it. The fact that I have a PCP who's very supportive and can talk to her and can herself write something supporting this. I'm really, really lucky.

I'm also really lucky to have the time and energy to do all the work myself to figure out how this process works and what needs to happen to give me the highest chances of it working. Just to have the brain space. If I was a lot sicker, I would not be able to do that.

This guy and his family from this ProPublica piece are an inspiration.

Also your job field gives you a little bit more of a leg up than somebody who might not have any idea about how any of this works too.

Yeah, and my political orientation, not believing that the company is being fair, knowing something about how for-profit healthcare works, that helps too. And it helps also just in feeling like wanting to fight it, feeling angry instead of depressed and hopeless. Which is kind of how I felt when the initial appeal first got rejected for like a week or two. It was just like why did I go through all this with the hope that something could be different? And I didn't see it coming either. I didn't understand. I’d never had to go past the first appeal with anything, so I didn't understand that there were more steps to take. I thought it was over. Then the more I learned about it, the more like rallied I got. I have a tattoo on my hand that says “thriving out of spite.”

I think I saw them play in the nineties.

Fairness was a really big motivator for me, and that's not true for everybody. I think part of that comes from growing up with some privilege and feeling like, you know, if you fight, you will win. That was the experience in my family, because they had the assets to fight for things.

What if anything do you want people to take away from this? And what do you think could be done in general or for your situation specifically?

Well, first of all, I want people who are in this position to know that they don't tell you everything, and not to trust your insurance or your doctor to understand how to fight for you. Or to tell you everything about it. Join groups for chronically ill people. If you have a particularly rare disease, join your rare disease’s organization and learn about how to fight for what you need. Because you do have more power than they tell you you have. You do have more options than they will ever tell you you have. And a lot of doctors don't understand themselves exactly what needs to happen because they're not the ones involved in doing insurance authorizations. Sometimes their staff haven't done this level of fighting. So that's the first thing.

It shouldn't be this way.

It shouldn't be this way.

It's too bad. But it's good advice, even though I wish that it weren't true.

It shouldn't be this way. There are organizations that can help you. There are patient advocate organizations. So if you are too sick to do this kind of stuff yourself, there might be people who can help you. But they are very full up. So it'll take a while. It'll take work to get into that. Just any help that people can get from their friends and family could go a long way.

When you're not chronically ill, or even if you are chronically ill and your medical picture is relatively simple, you have no idea what the experience of someone like me is. I think there's a confidence that people have when they have not had to deal with this in the system that is just really unfounded. So listen to and believe people who are sick, people who are disabled, because we are the ones who really know what the system is like and how fucked up it is.

That's something I often say. You sort of naively… I think a lot of people think, ok, if I get sick, the doctors will all fall in and take care of me and it will all work out. Not really though! You have to take care of yourself or your community has to help you.

You have to take care of you.

Here are some shout outs to other disabled people doing amazing work you might include in the newsletter, for readers like me who don't know where to start:

How to Get On is a site with plain language instructions and personal stories about damn near every aspect of disabled life. It covers some aspects of medical care, especially on Medicaid. I've used this a lot for myself.

Read the Sins Invalid Collective on the Disability Justice Movement.

Here is an upcoming Zoom class by Shilo George on getting medical care as a fat disabled person.