What do rich homeowners actually want?

My forthcoming book of short stories A Creature Wanting Form is available for pre-order now.

Aware that he only had a few months left to live the great Mike Davis gave one of his final interviews back in August to the Guardian. "You’ve been organizing for social change your whole life. How do you deal with a future that feels so bleak?" Lois Beckett asked.

"For someone my age who was in the civil rights movement, and in other struggles of the 1960s, I’ve seen miracles happen," the revolutionary and historian responded.

I’ve seen ordinary people do the most heroic things. When you’ve had the privilege of knowing so many great fighters and resisters, you can’t lay down the sword, even if things seem objectively hopeless.

I’ve always been influenced by the poems Brecht wrote in the late 30s, during the second world war, after everything had been incinerated, all the dreams and values of an entire generation destroyed, and Brecht said, well, it’s a new dark ages … how do people resist in the dark ages?

What keeps us going, ultimately, is our love for each other, and our refusal to bow our heads, to accept the verdict, however all-powerful it seems. It’s what ordinary people have to do. You have to love each other. You have to defend each other. You have to fight.

I believe that as well. Not always but I do believe it. It can be very easy sometimes to accept the verdict. To say fuck it. But on the balance you have to believe a better world is worth fighting for right? Otherwise what is the point of all of this? Of anything?

Davis' quote there calls to mind this stanza from Auden's September 1, 1939:

All I have is a voice

To undo the folded lie,

The romantic lie in the brain

Of the sensual man-in-the-street

And the lie of Authority

Whose buildings grope the sky:

There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police;

We must love one another or die.

And I imagine this part from To those born later is one of the Brecht poems he was referencing:

III

You who will emerge from the flood

In which we have gone under

Bring to mind

When you speak of our failings

Bring to mind also the dark times

That you have escaped.

Changing countries more often than our shoes,

We went through the class wars, despairing

When there was only injustice, no outrage.

And yet we realized:

Hatred, even of meanness

Contorts the features.

Anger, even against injustice

Makes the voice hoarse. O,

We who wanted to prepare the ground for friendship

Could not ourselves be friendly.

But you, when the time comes at last

When man is helper to man

Think of us

With forbearance.

Davis died this week at 76.

RIP Mike Davis. After it came out that he was transitioning to palliative care, I emailed him to send him my best and let him know about the overwhelming appreciation for him and his work I felt and was seeing across the board. This was his response: pic.twitter.com/aT2rYi5Jp2

— Matt (@MJHaugen) October 26, 2022

Reading through some of his work again since last night this stood out to me as a good philosophy for living as well from a piece back in 2011.

It's true that old radicals like me are quick to declare each new baby the messiah, but this Occupy Wall Street child has the rainbow sign. I believe that we're seeing the rebirth of the quality that so markedly defined the migrants and strikers of the Great Depression, of my parents' generation: a broad, spontaneous compassion and solidarity based on a dangerously egalitarian ethic. It says, Stop and give a hitch-hiking family a ride. Never cross a picket line, even when you can't pay the rent. Share your last cigarette with a stranger. Steal milk when your kids have none and then give half to the little kids next door — what my own mother did repeatedly in 1936. Listen carefully to the profoundly quiet people who have lost everything but their dignity. Cultivate the generosity of the "we."

Today Miles Howard writes for Hell World on a subject that happens to fall within one of Davis' regular topics: The wealthy pulling up the drawbridge and leaving working people behind left to eat shit.

Previously Howard wrote about the city of Boston's poor treatment of the unhoused population and the end of the eviction moratoriums.

Before we get to that though you will have missed this paid-only Hell World from the other day unless you're a subscriber.

I don't know whether or not it's "one of the good ones" but it's certainly "one of the kind of ones that people say are 'one of the good ones.'"

When was the last time you sat down for dinner with your family? Not like your extended family with your spouses and children and so on but the family you grew up with?

I had sort of become enamored with this idea that there was one day we all got together at the table and ate like a family and it was the last time that it happened and none of us knew it was happening and barely registered it as anything at all. Endings are easier to suffer through when you aren't aware they're transpiring. I know it probably seems like nothing to have dinner with your family but it is not nothing in our case. I can't think of the last time I ate a meal prepared for me by my mother outside of a holiday type of situation which is different for reasons I can't quite articulate. I worried on the way down that I might be forcing something here with this little stunt of nostalgic domesticity but it ended up being exactly what I wanted it to be. It’s not like I don’t want their children or our spouses around by the way but it’s a different thing if you understand me when your overlapping familial identities are fractured. One can't fully be a sister when one is also being a mother and so on if that makes sense.

Anyway subscribe to read it here.

What do rich homeowners want?

by Miles Howard

Before we begin, I should preface all this by saying that I grew up in one of those upper middle class suburbs north of Boston where homeowners band together to stop new affordable housing from being built. You wouldn’t get the impression that this is how things work by walking around my hometown or any of the neighboring suburbs that invariably nuke housing proposals. There are plenty of those “Hate Has No Home” signs on the lawns, and every block or two, you may even spot a BLM banner. But when it comes to any development proposals that might make it easier for “other people” to put down roots locally, a majority of cranks always materialize to vote down the possibility of adding multi-unit, mixed-income housing to the upmarket zip code.

A version of this conflict is playing out in many U.S. cities as well. Since the 2008 recession, our national rate of housing construction has lagged behind demand. Between 2006 and 2016, the number of American renters ballooned by 25%. And just like in the suburbs, there’s an inevitable bloc of city homeowners who overpack community input meetings whenever new housing comes up and literally shout down whatever proposal is on the slab. (A lot of these people are the same folks who demand a bolder solution to homelessness in their cities, which—evidently—would not involve giving homeless people actual homes.)

But what sets most cities apart from the wealthier suburbs is that your average American city will have some supply of public and/or subsidized housing. Sure, it’s not nearly enough. But there’s at least a precedent to build on.

The affordable housing debate tends to focus on cities for several reasons, not least of which is the fact that in cities, the anti-housing types have to lock horns with viable pro-housing groups like tenant rights activists. Renters constitute a major segment of city residents. Suburbs—long considered the realm of homeowners—are often overlooked as housing battlefields. But during the last couple of years, as the housing crunch has gotten even worse, some towns are seeing their shares of renters overtaking homeowners for the first time. Which makes you wonder: what happens when there’s not enough affordable housing to buy or rent in a well-off suburban area?

The answer is pretty simple. If there’s not enough local affordable housing, a lot of people who provide essential services to residents of these tony suburbs can't live there. So…they’ll leave and they’ll go somewhere else. Take teachers. Historically underpaid, stuck in that gray zone between making too much money to qualify for housing assistance and not enough to afford to live near their workplace, a growing number of educators and support staff are resigning from their posts. In Aspen—one of Colorado’s most expensive zip codes—the “labor shortage” grew so dire that the town’s school district superintendent started moonlighting as a school bus driver.

Each state has its own variation of this kind of churn, as teachers and manufactured housing scarcity collide. Earlier this year, North Carolina’s EdNC conducted an online survey with roughly 1,000 K-12 teachers to get a sense of their housing situations. 71% of the responding teachers agreed that lack of affordable housing was a serious barrier to teaching in their school districts. “Young teachers today are paying more for rent near my school than I am paying for my mortgage on a 3,000 plus square foot 2 story brick house!” one K-12 teacher commented. “Housing is very expensive and not affordable for young teachers just starting out. Most teachers work two jobs.”

Left unaddressed, housing scarcity will start to squeeze a wider spectrum of essential workers. Resort towns where the wealthy sunbathe and ski offer some of the most extreme glimpses of where the suburban housing crunch could soon lead. A recent New York Times story explored the hardships faced by teachers, hospitality workers, and even firefighters in Sun Valley, Idaho. Home prices in the region have grown by 50% in the last two years, and the average rent for a two-bedroom apartment has lept from $2,000 to $3,000 a month. Exacerbated by wealthy buyers relocating to the area in the work-from-home era, Sun Valley’s housing crisis has yielded stories that read like scenes from a Cormac McCarthy novel. There’s the high school principal who went from living in a camper to a micro-apartment in an industrial building, the house cleaner who has to wash her dishes at a local park due to having no sink, and the small business owner living out of his box truck who has to search the forest each evening for a new parking space.

These horror stories point to the possibility of well-off homeowners growing so paranoid about working class outsiders changing the nature of their enclaves that they end up repelling the very people who are already providing essential support to these communities. You would think that retaining teachers and firefighters by ensuring some supply of affordable housing would be an existential concern for a place like Sun Valley. But evidently it’s not, and it invites a question that I’ve been asking myself for the last couple of years, working as a journalist and reporting on the shortage of affordable housing at a time when the most comfortable homeowners continue to block new apartments and houses from being constructed.

What do rich homeowners actually want?

At its most base level, the manufacturing of an affordable housing shortage is an instinctive flex. It’s people with the fortune of having homes and wealth guarding what they’ve got, no matter the cost to their neighbors, their wider community, and in the long run, themselves. Some may chalk the whole thing up to protecting their assets: the inflated valuation of their property. Other homeowners might see the prospect of sharing their zip code with working people as compromising the exclusive privilege of being able to live there—a privilege that homeowners have paid for.

That sense of having bought admission to an exclusive echelon can manifest itself in strange ways. A few summers ago, a friend and I went swimming at Farm Pond, a vast swimming hole in suburban Massachusetts that’s surrounded by multi-million dollar homes and mostly closed off to the common riff-raff. We walked in through the woods on a little-known public path. After splashing around, we paddled over to one of the nearby lakeside houses for a cautious glance. No sooner had my friend stepped onto the grassy banks when a large, red-faced man emerged from the porch door of the house, waving his hands, screaming about how much he paid in property taxes each year, and threatening to call the cops if we didn’t clear out immediately.

Most wealthy homeowners will avoid this type of belligerent confrontation, but choking off the supply of affordable housing in their vicinity basically sends the same message to the general public: We paid to be here, and if you can’t, then get lost. I’m increasingly convinced that this is it—that the desires of the wealthy homeowner run no deeper than territorial entitlement. And what gilded enclaves such as Sun Valley are showing us, in stark fashion, is that the rich homeowner’s desire is antithetical to a functioning society: even the localized society of a rich town!

A handful of well-off suburbs are starting to get it. Palo Alto has greenlit 110 new apartments that will be priced and prioritized for teachers. Back in March, Hawaii’s state legislature was considering a bill that would catalyze similar teacher housing development near Oahu’s Ewa Beach. But elsewhere, the home owners are digging in. A proposed tax hike which would have funded affordable housing in Sun Valley was shot down by homeowners. In Massachusetts, a recent zoning change that requires suburbs to build new housing in the vicinity of train stations has led some towns to choose fines from the state, an acceptable price to pay for preserving exclusivity.

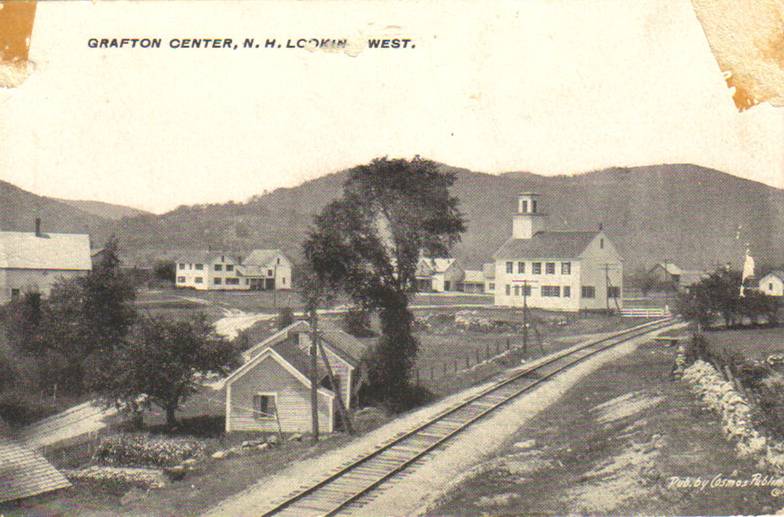

In the short term, the people who need housing will pay the greater price, as their limited options force painful choices about holding onto a job and staying rooted to a community. But it speaks to the rich homeowner’s lack of long term vision or desire that the ultimate price of affordable housing scarcity does not seem to have registered yet, despite what’s clearly happening in Sun Valley and other strongholds of wealth. So let me close with a particularly vivid picture of where that road leads—the town of Grafton, New Hampshire. As chronicled by Pat Blanchfield for The New Republic, the early 2000s saw Grafton overwhelmed by libertarians from the Free Town Project, an organized effort to take over a town and transform it into a Randian haven. Once situated, the Free Town people went after the Grafton municipal budget, shaving it down to less than $1 million. Roads deteriorated. Violence broke out between neighbors. And eventually, the local black bears moved in, lured by the promise of garbage from unsecured dumpsters and residents who would knowingly feed the bears. They tried to claw their way into people’s homes.

This is what the rich home owner still doesn’t comprehend. No amount of equity will stop a bear from breaking down your door. But a local wildlife cop can—especially if they live right down the road.

Miles Howard is a writer covering urban living, outdoor recreation, and how to socialize them. His work has appeared in National Geographic, The Boston Globe, VICE, Shelterforce, and the Washington Post. He lives in Boston.

Thanks for reading everyone. See you next time probably. Check this out:

if you’re wondering how insanely low the Mississippi River is right now here’s me on a massive sand dune in the middle of it near rosedale, mississippi pic.twitter.com/Iw2Asky7Qv

— Virginia Hanusik (@virginiahanusik) October 25, 2022

Here's a nice song for the road.