They might do something about it.

The breathless madness of fear

Down below Austin L. Ray writes on the return of TV on the Radio and how to make a life in the arts. First up a report from Justin Glawe on election deniers in positions of local power around the country and the threat they face to this upcoming election.

Previously for Hell World Glawe reported from Springfield, Illinois after the release of body cam footage showed police murdering a woman named Sonya Massey in cold blood in her own home.

Elsewhere Ray wrote about his effort to raise money to cancel medical debt in Georgia.

He also wrote about his favorite Jason Molina songs.

Help pay our great contributors by supporting this newsletter with a subscription please and thank you.

Collective hysteria

by Justin Glawe

It was a woman named Pam that made me realize how far gone we are. I’ve known it for some time, but it wasn’t until I heard her voice quivering as she explained how her morning had gone that I fully understood the breadth of what we’re facing, and the seeming hopelessness of overcoming it.

“The first thing this morning, I got on Telegram and the first thing I see, a smarter person than me, Elon Musk. ‘Election voting machines and anything mailed is too risky. We should mandate paper ballots and in-person voting only.’”

“That just kind of grabbed my attention,” Pam said of a Musk tweet. “I wasn’t planning on speaking today.”

We live in a world run either by cliched villains or outgunned mean-wells. If that weren’t bad enough, these former actually inspire people. Pam had walked to a microphone at a podium at a county commission meeting in Reno, Nevada and came into my life that day because a tweet from Elon Musk about election fraud had inspired her to take action. Few things in these last four years — which I have spent documenting the mass hysteria of election denialism — have struck me with such a strong sense of doom as Pam’s testimony at a meeting of the Washoe County Commission on July 11.

Part of it was her look — she looked like someone who is friends with my mom. Part of it was her demeanor — upbeat from her weekend birthday celebration but deeply serious, sounding like she could cry, when she began expressing deep concern about things she had heard about immigrants living in public housing in the area.

“The last time I was at the podium, I told you a story about a social worker that told me all her clients are refugees now. So that’s our money, paying to help them, in the millions,” Pam said. “People that are here four days from other countries are getting work permits. How is that possible? They’re here four days, and they get to take jobs to lower our wages? Is that where all this affordable housing’s coming from? Is that to cram all these people from 150-60 other countries in here, to lower our wages, and ruin our quality of life?”

I felt pity and sadness for Pam, not simply because she is filled with an unjustified, soul-harming fear of immigrants, but because I know she probably wasn’t always like this. I know, as a result of years of reading the online postings of people like her, that something changed inside of her. Whereas she once believed that the world was generally a good place, she no longer does. Through her Facebook account — or Telegram, or Twitter, or Instagram or any of the other mainlines of internet infrastructure she has plugged herself into — Pam has learned that the world is an evil place filled with bad people. She knows this because people she trusts and admires, people like Elon Musk and Donald Trump, have told her so. So, Pam is gone. And she’s not coming back. Neither are so many of her friends and millions, or tens of millions, of Americans.

I would get on my knees and thank God every morning that my mom doesn’t have Facebook, but I don’t because I believe my mom is too smart to get sucked into this madness. But that’s the thing with the hysteria of political misinformation: it takes people you wouldn’t think that it could.

Many of those people work in local elections. At last count on a spreadsheet I’ve been building for the last four years, almost 100 election conspiracists work as local election officials, nearly 70 of which are in positions of power over election administration in six swing states. At least one of them sits on the Washoe County Board of Commissioners where Pam was trying to convince the board to refuse to certify the results of the June election. On that day, Pam and other election denial activists — many of whom are just regular folks who have been swept up by the cause — were successful.

Listening to Pam and others speak for hours ahead of their vote to certify the June election results were three Republicans and two Democrats on the board. I already knew that two of the Republicans — Jeanne Herman and Michael Clark — were going to vote against certification. Herman previously voted against certifying election results, which in recent years has become an increasing practice among local election officials who support Trump and his lies about widespread voter fraud. (At least 35 local election officials have refused to certify results since 2020, according to an August report from Citizens for Ethics and Responsibility in Washington.) The third Republican listening to Pam and others that day was Clara Andriola, who had previously voted for certification alongside the board’s two Democrats. In fact, Andriola had already voted to certify the election that was being questioned by Pam and others — that election included Andriola’s victory over a primary opponent who is an election denier.

When it came time for the vote, Andriola reversed her position, voting not to certify the results of her own election.

Repercussions swiftly followed: the Nevada Secretary of State asked the State Supreme Court to force Andriola and her fellow Republicans to certify results. While that case got hung up in court, Andriola and Clark reversed their previous decision and certified the election results. Still, Herman voted against certification. (For a better understanding of what certification is supposed to look like, consider Democratic lawyer Marc Elias’ analogy: local election officials like Andriola are simply the scoreboard in the game of elections. Their job is to look at the score at the end of the game and note the number of points for each team. These officials are not referees, whose job it is to ensure that the game was played fairly. In this analogy, referees are the courts, where challenges and demands for recounts and audits play out.)

Despite what election law experts have repeatedly said is the mandatory, score-keeping task of certification — which in Georgia has been deemed “ministerial” in court cases dating back to 1899 — Republican election officials have their own interpretation of this non-discretionary duty. Like Trump, they think they’re smarter than all the people who’ve spent their lives and careers studying this issue. Since 2020, these officials have refused to certify results at least 35 times in eight states. Luckily, they’ve been outvoted by their colleagues, who are either Democrats or more moderate Republicans, but the act of voting against certification isn’t necessarily the point. The end result of certification refusals is more distrust in elections and — in a way that is beneficial to Trump — fomentation of claims that the coming election will again be “stolen” from him.

Once results are certified by counties, it’s up to governors and secretaries of state to approve final, statewide results. Those officials could selectively certify results that favor Trump, allowing Republicans to try to enact alternate slates of presidential electors like they did in 2020. After that, a Congress again led by Speaker Mike Johnson could engage in all sorts of parliamentary maneuvers to decide amongst themselves who won the presidential election, as was troublingly laid out by a pair of ex-White House staffers for former presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton at the Washington Spectator in January.

If you don’t think this is possible, recall that Johnson was the architect of the election version of the independent state legislature theory that posits state legislatures can decide for themselves how to allocate electoral college votes if they think an election is beset with fraud, and that Johnson was put into his position precisely because he will back Trump’s unconstitutional attempts to retake the White House.

So, election deniers overseeing local election administration: check. Red state governors who can back faulty refusals to certify election results: check. A MAGA Congress that can then try to manhandle Trump to a second term: check. The period between Election Day and Inauguration Day is shaping up to be a turbulent time in which, once again, all of our institutions will be tested by the strength of Trump’s authoritarianism — efforts that are backed by many of our fellow Americans.

The public actions of local election denial officials, like those who have refused to certify results in recent years, are one way to gauge support for the madness of Trump’s election lies. But over the past four years I’ve found another: many of the officials I’ve come across in my research are older and white, which means they’re on Facebook. And for many of them, they post constantly. The content reflects the breathless madness of fear, rage and entitlement pumped out by a right-wing ecosystem of content creators. Themes of Christian nationalism abound, as do support for political violence and open racism.

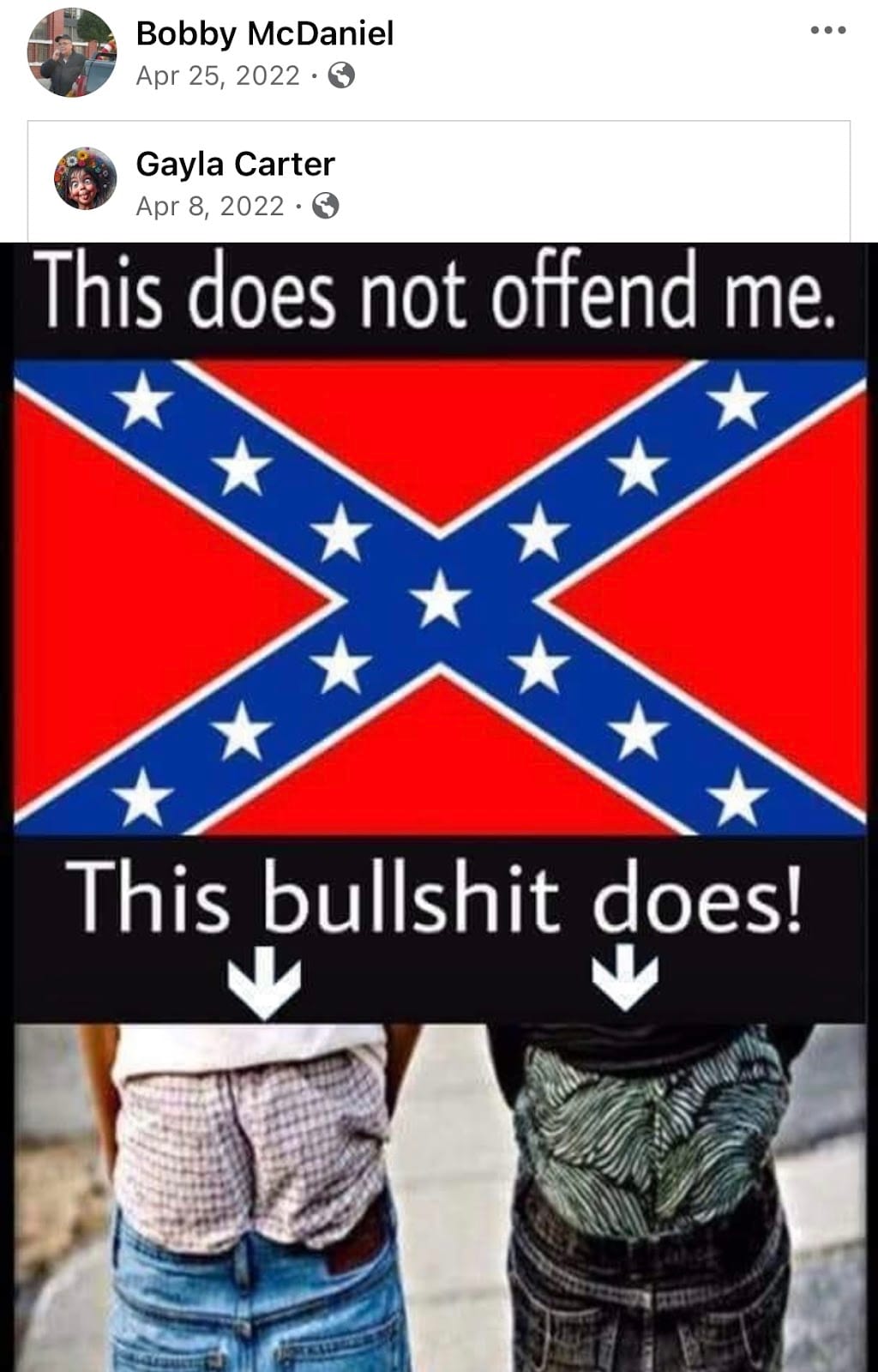

Take Bobby McDaniel in Alcorn County Mississippi, for example. McDaniel was elected to his position in a county where less than 10 percent of the population is Black. McDaniel is one of the most prolific posters of insane right-wing content among the many local election officials I’ve come across. In the aftermath of January 6, 2021, McDaniel wrote that the threat of life in prison was “not much of a deterrent” to apparently carrying out violence on behalf of Trump. He has speculated that the rioters at the Capitol that day were “Antifa or BLM,” organizations that should be deemed to have committed “treasonous” acts and subjected to “severe penalties after a military trial.” He has shared debunked conspiracies about ballot harvesting and other election denier nonsense. And of course McDaniel has shared “white lives matter” content and racist memes.

In June 2021, McDaniel wrote a screed about something he had seen on TV.

“I just watched an ad on TV that announced an upcoming Black Entertainment Awards show,” McDaniel began. “The ad also claimed a ‘Black Only’ format, in other words no Whites allowed. Let’s reverse that with a Whites only awards show and watch Jesse Jackson leading protest marches against anything White all over America, Al Sharpton crapping his diapers full and Jussie Smollett found in a pool of blood after being whipped with a ‘My Pillow’ by a gaggle of White racists. Folks we have pandered much to long (sic) to a small segment of people that hate anything not black.”

The fact that someone this ignorant could even rise to such a position is concerning. Worse, McDaniel is far from alone, especially in the South.

Among the many election denial officials in Georgia is Ben Johnson, a QAnon-believing, Elon Musk-worshiping head of an IT company who also chairs the Spalding County board of elections an hour south of Atlanta. Johnson is another prolific poster of right-wing culture war outrage. When it comes to elections, Johnson’s specific kink involves Dominion voting machines — which you’d think the head of an IT company would know are not really susceptible to fraud. Still, Johnson and his fellow election deniers in Spalding County have made it their mission to do away with voting machines in favor of hand counts that they admit are unreliable. A couple years back, I even caught them in a failed attempt to hire an Atlanta company to illegally access voting machines in Johnson’s manic hunt for non-existent election fraud. This scheme had already been carried out in Coffee County, Georgia, where the same company was involved in an illegal breach of election equipment there. The only thing that stopped Johnson and his election denial confederates was a warning from the county attorney that what they were doing was probably illegal.

All those people are still in power. In November, another election denier on the board, Roy McClain, publicly voted not to certify election results only to privately sign off on those results on an official government document. This was an apparent attempt to appease the MAGA masses while also avoiding exposing himself to lawsuits and legal penalties for refusing to certify results. In true Trumpian fashion, McClain then doubled down on his fake “no” vote on certification and complained in February about a letter he’d received from Georgia Democrats admonishing him for the vote. At no point in his brief screed on the letter did he clarify for the public that he’d actually approved certification by signing the official document I discovered.

In other words, McClain doubled down on something that was not just ethically wrong, but perhaps a violation of his oath of office, not to mention Georgia law, in order to maintain his election denier bonafides even though he hadn’t actually committed the act that election deniers support.

All this shows that we exist in a strange land between failed state and redemption. I don’t see an obvious path toward the latter, but surely it does exist. Maybe if some of these folks would get off Facebook and instead read reputable news outlets they could be saved, but that probably isn’t going to happen. Instead, they’re doomed to continue being consumed, eaten alive by the very algorithmic content they believe is freeing them, but is actually enslaving them in an alternative world of strange conjecture and hateful fear. It’s difficult to imagine how our fellow Americans can pry themselves away from such an addictive and powerful elixir.

With so many people like Pam in Washoe County out there believing false claims of widespread voter fraud, our country is primed to be split into camps who either believe that elections are free and fair and those who won’t accept any results that show their side losing. Does that go away if and when Trump finally leaves the political arena? Probably not. We live in a world of alternative fact, where even universally-accepted truths like Hitler being a bad guy are up for debate among the American right. In that world, how can we expect reason to prevail?

Much of this is Facebook’s fault. It’s also Republicans’ fault. It’s our fault too as a society that’s focused more on the acquisition of material things and monetary success than it is the fulfillment through our work and personal lives that could prevent so many Americans from seeking a sense of belonging via the political us vs. them paradigm. It’s vulture capitalism’s fault for killing local newspapers that could still be reporting on issues that remind us we largely agree on more than we disagree on, and that it’s better to pay attention to what your city councilman is saying than the president because the former can fix potholes and the latter makes decisions that largely don’t affect you. The degradation of local news has reversed the conventional wisdom that all politics is local, replacing it with a sense that everything that happens in our communities is the product of opaque, larger forces that can only be stopped by paying attention to every minor development coming out of Washington.

But mostly it’s Trump’s fault. He lost and couldn’t handle it because he is a broken man. Unable to accept that he is not liked by a good portion of the country, he concocted a lie to convince the world — but mostly himself — that he’d actually won the 2020 election. Since then, knowing that he’ll probably lose again, he has planted the seeds of another lie that may result in even more disastrous consequences than an attack on the Capitol like the one that occurred on January 6. Just yesterday, he ranted on Truth Social that “WHEN” he wins in November, he’ll hunt down anyone who “CHEATED” in the election and imprison them.

The 2024 version of Trump’s election lie is no different than the old one — except this time, he’s being proactive about it. Instead of waiting until he loses to claim that the election was stolen from him, he’s making those claims now with the help of a sprawling army of propagandist media, super PACs, think tanks, and the full weight of the Republican party establishment behind efforts to call November into question — to overturn it, in fact — before a single vote is case.

The question isn’t whether there will be political violence as a result of Trump’s lies but when and in what form it will come. Things will be worse then. People like Pam in Washoe County, already gone, might get even more fired up. They might do something about it.

Justin Glawe is a writer and journalist who writes the newsletter American Doom, where he covers election deniers, right wing extremism and other threats to democracy.

When the chariot arrives you'd best enjoy the ride

by Austin L. Ray

Honestly, I feel kind of bad for the people who only know TV on the Radio as “the band who did that one fantastic performance on Letterman.” They’re not wrong, of course. It was spectacular—the kind of thing where you read the top YouTube comment calling it “arguably the greatest live music performance in history,” and the only reasonable response is, “You know what, @windyhillbomber? I can’t argue with you there, brother.”

Fuck it, you got four minutes? Let’s watch it again:

Eighteen years ago almost to the day, frontman Tunde Adebimpe sang at the sky and whipped his hands around like a manic preacher man. Guitarist and vocalist Kyp Malone hacked away at a Gibson SG and bopped and levitated around his part of the stage. Guitarist David Andrew Sitek and late bassist Gerard Smith barely moved in their respective corners, locked in as they were on the vibe. Drummer Jaleel Bunton sat between them, simultaneously holding it all together while propelling it forward, barely able to keep it the whole thing from careening off the rails.

Of course, your eyes linger on Adebimpe, a generational talent when it comes to fronting rock and roll bands, and moreover an example of how to live a life in pursuit of art in all its weird and sometimes rewarding ways. “We’re howlin’ forever,” he shouts over and over toward the end, and it feels like maybe we really are, maybe we really can.

As the fury subsides and the feedback hums, we hear Letterman grunting approvingly as he makes his approach. “Yeah, I guess so. Yeah. Cool. Aw, that was nice. That was great.” And then he delivers an all-timer Dave Band Compliment: “TV on the Radio! That’s all you’re looking for!” I’ve probably watched this clip a hundred times, and I still chuckle when he says it.

Adebimpe reflected on the performance recently, noting that the band went to a bar that evening to watch it and were happy enough with it. What they didn’t realize was that they’d chalked up an artistic milestone. They’d made something they were proud of that resonated with strangers.

“The next day, Kyp and I were on the subway and everyone was staring at us. We got out to the street and, again, everyone was staring at us. Everyone was super complimentary, but it was weird, it was an instant reminder that ‘oh, we were on the TV! We were everywhere.’”

Before there was “Wolf Like Me,” there was “Staring at the Sun.”

In 2003, I was trying to figure out what it meant to be a music writer at the student newspaper at the University of Missouri-Columbia, a publication called The Maneater, a place with a sign at the front of the newsroom’s office that reads, “where life is a Hall & Oates song.” My young, optimistic ass had decided at some point in the years previous that I wanted to be a journalist—or at least a writer in some fashion—and then after not enjoying the one journalism course I took at Mizzou, I started taking various writing classes and hanging out at newspaper meetings.

Eventually I started writing about music. It was a perhaps unsurprising turn of events for people who knew me—I’d always loved music and I’d always loved writing, so why not put them together? But it seemed foreign and exciting to me in a way not many things had in my early years. I got my first taste through album reviews, then started interviewing artists, then realized anything was possible and would end up helping create an arts magazine for the newspaper, serving as A&E editor, and making lifelong friends along the way.

But this part is supposed to be about “Staring at the Sun.” Interest piqued by the Pitchfork review, I bought the Young Liars EP on CD shortly after it was released during the summer of 2003, and it was instantly in heavy rotation. By the time my arts newspaper squad had reformed in the fall, we were all listening to it, but “Staring at the Sun” was the clear favorite of our gang, the obvious single, as it were. More than two decades later, this shit is still pure poetry as far as I’m concerned:

Note the trees because the

Dirt is temporary

More to mine than fact, face

Name, and monetary

Beat the skins and let the

Loose lips kiss you clean

Quietly pour out like light

Like light, like answering (the sun)

Chatting with one of the newspaper pals recently, trying to remember how we could’ve ever been so young, but also literally just trying to remember what happened over that next year, we decided that we saw TV on the Radio live at least twice in Columbia, Missouri around that time—once headlining at a now-defunct club called Shattered and once opening for The Faint at a bigger venue called The Blue Note.

Seeing them perform really took my fandom over the edge, simply because they are a better live band than 99% of live bands. They reinvent the songs completely, speed them up, slow them down, twist their genres, turn them into something new and unpredictable. If you’re unfamiliar with the band, the “Wolf Like Me” clip above is one version of this phenomena, and I’d suggest this clip of “Young Liars” if you wanna see the other side of it.

Let the Devil In is another must listen:

But in the back pocket of a discarded pair of jeans

Is a priceless ticket to the grandest opening

So when the chariot arrives, you'd best enjoy the ride

'Cause when we get to heaven's gate we're not getting inside

I don’t know why TV on the Radio has taken so much time off from music. Until recently, their last live gig was opening for Pixies and Weezer at Madison Square Garden, and their last album was released 10 years ago. Their latter albums in particular walked a satisfying line—at least to this longtime listener—between unusual art rock and catchy, almost-slick songs that appealed to a broader audience and the lucrative side quests that come with that.

I still remember hearing “DLZ” in a Breaking Bad episode toward the end of season two. This is a band that draws a crowd. A band that Phish covers on the regular. Surely they could’ve kept churning out albums and finding similar success if they wanted to. But making a living making art is about more than just cashing a check sometimes.

While the group’s members have dabbled in various other bands, production roles, and collaborative opportunities, Adebimbe has been the most visible. Before TV on the Radio, he worked as an animator on MTV’s Celebrity Deathmatch, and he’s since followed his muse into comic books, gallery exhibitions, and several television shows and movies, including, most recently, a scene-stealing role in this summer’s Twisters. It’s an inspiring way to live, in my opinion—he’s one of the people I look to for inspiration when I think about how I pay my bills by writing words.

But I’m increasingly unsure what to tell people who want to make art for a living. After college, I left the midwest in a permanent way for the first time, landing in Atlanta for an internship at a music magazine that would eventually turn into a job. They offered me $24,000 a year to run their website, which is maybe even more bleak to think about today than it was in 2006. I made ends meet by freelancing on the side and working nights and weekends at a record store. It would take me 10 more years—which included a layoff, a rehire, a ton more freelance, and eventually leaving the magazine for a marketing company—to find a way to live off my words, stop doing “just for money” freelance, and put together a constellation of projects that I enjoy doing every day. I’m happy to say that I now have a flexible, creative day job I enjoy and the ability to work on things I care about on the side that don’t make any money. I rarely write about music anymore, which would’ve truly shocked College Austin.

While I’ve never had anyone stare at me on the subway, it has gotten to the point where a couple times a week some kind person in public tells me they follow me on Twitter, asks me if I’m the How I’d Fix Atlanta guy, or wanna know where they can get a good sandwich. It’s always weird when this happens, but I’m starting to get used to it. It’s also always, always an honor to know that some words I wrote somewhere resonated enough with a stranger for them to say something about it to my face.

If you wanna create stuff for a living, it can be so hard to find the things that pay the bills and the things that give them creative fulfillment, and then try to keep enough of those fulfilling things in the mix so that the balance is right. But maybe that’s the answer we should be giving to people who wanna make art as a job. Do as much of the stuff you love as you possibly can and do as much of the stuff that provides money and security as you have to in order to support the good stuff?

I was thinking about all this when TV on the Radio announced those 10 dates recently, shows that will happen in New York, Los Angeles, and London. Ostensibly a way to promote the 20th anniversary reissue of Desperate Youth, Blood Thirsty Babes, they could very well be the warm up for more in 2025—a world tour, maybe even a new album. At the very least, it sounds like we’ll have a solo Adebimpe record at some point soon.

But this could also just be a few guys in their late forties and early fifties looking for a way to pay off their mortgages and continue to be chill art dudes that do what they want as they age. Ain’t nothing wrong with that. There are worse ways to live. As an aging writer who wakes up everyday thankful and surprised that I can write my little words and pay my little bills, I hope to end up there one day as well.

Austin L. Ray is a writer in Atlanta. Follow him on Twitter if you want.