They're all just tired, emotionally drained and done

Down below we have an excerpt from the new book Crisis and Care: Queer Activist Responses to a Global Pandemic available today via PM Press. You can jump directly to the essay on the Hell World site here:

First here's me on the "teacher shortage."

The teacher shortage continues in Wisconsin as the shortage in Vermont has schools scrambling. In Arizona they’ve made it so you no longer need a bachelor’s degree to teach and in Iowa they’re offering $50,000 bonuses to entice teachers to stay. In Los Angeles the teacher shortage is of course affecting underserved schools the worst. In New Jersey even as schools are open in the “post-Covid era” they’re turning to more virtual teachers to fill in for vacancies and in Florida as you’ve likely heard they’re trying to make up for the glaring lack of credentialed teachers with troops and cops. It’s a problem in Texas and in North Carolina and in Indiana and basically everywhere else in the country right now too. It’s become a problem in Massachusetts too where teachers are paid relatively well compared to the rest of the country.

Earlier this year the National Educators Association polled their union members and found that 55% were considering leaving the profession earlier than they had planned. Double the number that said so in 2020.

“The top issue facing educators right now is burnout, with 67% reporting it as a very serious issue and 90% a very serious or somewhat serious issue,” they reported.

All of that stress is a compounding problem. As more teachers leave an increased burden falls upon those who are left behind to pick up the slack leading to more wanting to leave and on and on.

Around 75% said that they’ve “had to fill in for colleagues or take other duties due to these shortages” according to the survey and 80% reported that “unfilled job openings have led to more work obligations for the educators who remain.”

As they note via the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics there are 600,000 less educators working in public education now than in 2002. Sorry fewer educators. A teacher would want me to correct that.

Teachers have long faced stressful conditions but – as I’ve written in here a hundred times in the past couple years – everything that was already bad about anything in this country was only further exacerbated by the pandemic.

The widening cracks in the already unstable foundation have impacted both teachers and children alike as well as the ways that teachers are supposed to respond to the children about these worsening problems.

“School leaders and districts started last year acting like it was a normal year,” one teacher in Massachusetts told me about the non-response to very difficult times.

“They didn’t account for all the trauma, and not just from losing loved ones, that kids experienced. Teachers see it and want to respond in thoughtful and caring ways, but they get no support. Kids hadn’t interacted with other kids in over a year and teachers were still being asked to [focus on prioritizing testing data.]”

SUBSCRIBE TO SUPPORT THIS NEWSLETTER

On top of the actual threat of and fallout from the ravages of Covid we can add the idiotic politicization of school’s responses to it all in terms of menacing anti-mask protests and the fierce open/close debate.

You can see why so many might say fuck this I’m done. This is not my problem anymore.

That’s before we even get to the increased scrutiny on subject matter in classrooms and the book bannings and the threatening terror campaigns being waged against teachers by local citizens and powerful politicians alike in which even the merest mention of LGBT issues puts a target on their backs. Not to mention the fear of mass shootings in schools and the reactionary response to further militarizing them which perpetuates itself in its own horrific sort of feedback loop.

A teacher in St. Paul, Minnesota told me that while they are paid well and have a strong union they chalk up the exodus to teachers elsewhere “not being paid enough to deal with dismantling of union power and the Critical Race Theory/groomer panic,” as well the lack of safety protocols in response to Covid.

“It's a very liberal city so there's virtually none of these CRT panic or school board meeting psychos,” he said. “But I legit cannot imagine being a teacher in Texas or Florida with all of this ‘Here's a hotline to call if your child's teacher reads a book we don't like’ shit."

"Teaching was a stressful enough job before all of that stuff and when you keep piling things on I think people just say forget this," he said.

Something I say a lot is I don’t know how you do that job. I mean I literally say it a lot to my wife. I’d say it to her right now but she’s at a meeting at school. She is already working again most days over her generous summer vacation some of which she also spent taking classes of her own like she does every other summer.

No but seriously how do you people do that job? I still have flashbacks to my stint substituting after college and getting absolutely roasted by kids all day.

“Economically the job just doesn't pay enough to cover rising rents and cost of living,” another teacher told me. “You'd have to run one or two extracurriculars to make up for it, and then you're left with no time to be a person outside of your job.”

“That's combined with no support from the administration, [dealing with] parents, etc. It’s just a lot of disrespect heaped onto the position and a constant framing of your responsibilities as 'What more can you give us though?'"

They said a colleague left last year for a job in data analysis at an investment firm.

“She's making a bit more money, with room for upward mobility, and not even 10% of the stress.”

The stress is a common refrain. The lack of support for addressing it as well.

"I really believe that schools are broken," a fourth teacher told me.

"The institution of schools and the students that they serve just no longer work. I have been an instructional coach for the past two years mostly working with new teachers. At the end of this school year, they all left. Every single one of them plus many more."

Why did they leave?

"Being micromanaged, blamed, not paid enough, and the constant use of cellphones with little to no support from administrators and parents. Seeing inequity on a daily basis, and trying to work against a system that created it, is exhausting and usually nothing ends up coming from it. They're all just tired, emotionally drained and done."

Teachers are indeed being underpaid right now but they have always been. It’s just that that underpayment is a lot easier to swallow for dedicated educators who love what they do when all of these other more recently worsening factors aren’t heaped on top of them.

Hold on though I should clarify perhaps a little belatedly that calling all of this a "teacher shortage" isn’t really an accurate way to talk about it. To mangle the old Bobcat Goldthwait joke about getting fired: We lost our teachers. Well we didn’t lose them, we know where they are, they just don’t want to come in anymore...

Much like how business owners and the people who write articles on their behalf in newspapers keep repeating the lie that “nobody wants to work anymore” it’s not that there’s an actual shortage of teachers (although there might be some of that coming down the line if trends continue because what young person would want to sign up for all of this) it’s that there is more specifically a lack of teachers (and workers in other fields of course) willing to do the job under the current conditions for the pay that is being offered.

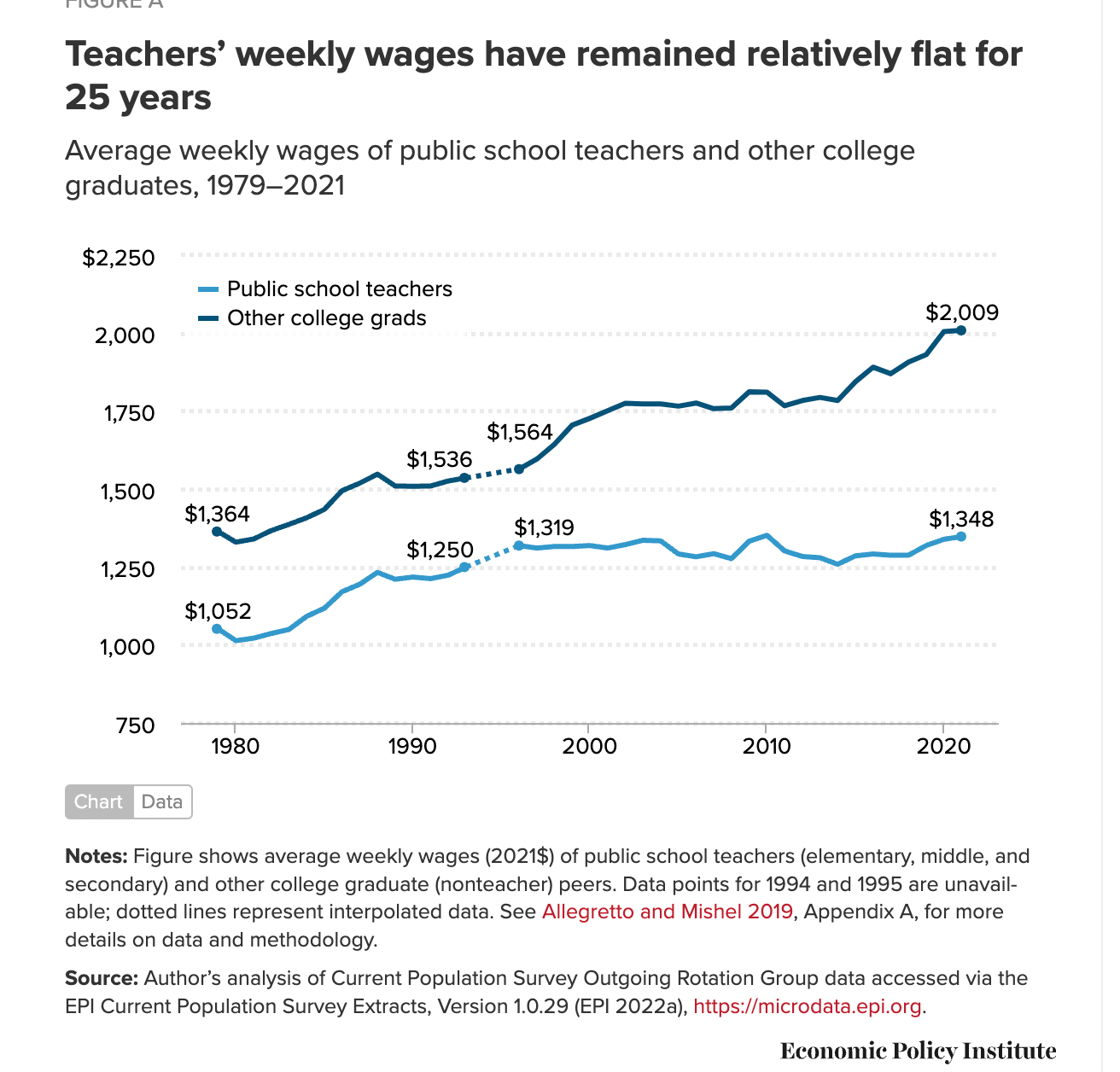

And unlike some other even more woefully underpaid professions teachers are perhaps realizing they have a few more options in terms of career latitude. The idea that they are underpaid isn’t just based on vibes to be sure. Almost everyone is underpaid everywhere but teachers also happen to be specifically underpaid relative to other workers with a commensurate education level. (Which I should pause to point out requires an extensive burden in terms of loans to be even able to achieve.)

The Economic Policy Institute has been tracking the so-called teacher pay penalty and it's only been getting larger over the years.

“Simply put, teachers are paid less (in weekly wages and total compensation) than their non-teacher college-educated counterparts, and the situation has worsened considerably over time,” they write

“Prior to the pandemic, the long-trending erosion in the relative wages and total compensation of teachers was already a serious concern. The financial penalty that teachers face discourages college students from entering the teaching profession and makes it difficult for school districts to keep current teachers in the classroom.”

Tens of thousands in debt for years and years of education only to be disrespected daily by administrators and politicians and parents and children every day? Can you blame someone for instead going to work at some bullshit email job instead?

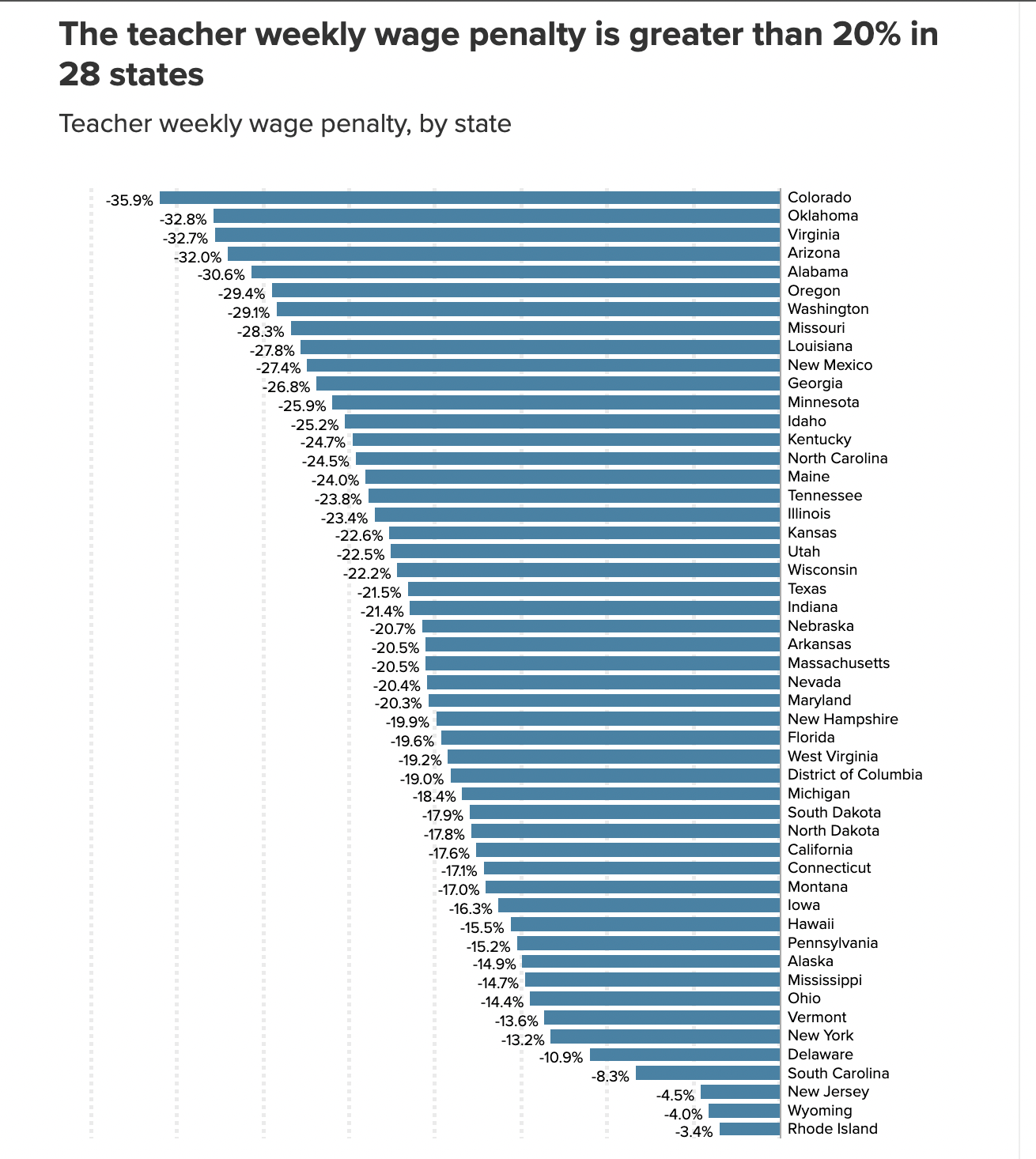

This is a nationwide problem in blue and red states alike by the way.

"In no state does the relative weekly wage of teachers equal or surpass that of their non-teaching college graduate counterparts," they write.

Despite some of the moves and public statements about how they're trying to address the issue from Republican leaders around the country it's hard not to imagine them pleased with how this is all transpiring. After all defunding (a very scary word!) all public services to the point where they stop functioning well and can therefore be used as an example of why they should be privatized (much like we've seen with the USPS) is almost the entirety of the conservative project.

So what's the answer?

Well the answer as always is fucking pay people more.

I understand this is a very hard idea for many in this country to process however so in the meantime I'm reminded of something Ryan Cooper tweeted (only half-joking I think.)

"Redefining all possible public goods as somehow part of the military is one of the few promising strategies I can think of. Everyone who's been to public school is now a veteran eligible for VA insurance. High speed rail is vital defense infrastructure. Cutting greenhouse gas emissions is protecting national security."

Perhaps DeSantis is onto something down in Florida. Could be that sticking cops and troops into schools isn't such a bad idea after all if only for one reason alone: It might be the only way to get politicians – Republican and Democrat alike – to actually send them the money they need.

The following essay by Zephyr Williams is excerpted from the newly released anthology Crisis and Care: Queer Activist Responses to a Global Pandemic (2022, PM Press), which looks at how LGBTQ+ people and communities responded to the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, and what lessons were learned that could be applied to future crisis points. Order a copy of the book here.

Breathing in Solidarity

by Zephyr Williams

Let’s all pause and take a collective breath. Inhale for 4 . . . 3 . . . 2 . . . 1.

Hold for 7 . . . 6 . . . 5 . . . 4 . . . 3 . . . 2 . . . 1. and

Exhale for 8 . . . 7 . . . 6 . . . 5 . . . 4 . . . 3 . . . 2 . . . 1. . . .

The first year of the COVID-19 pandemic was intense, a veritable game of social justice whack-a-mole. It felt like every time we started getting an ounce of control over one situation another one would pop up, laughing maniacally as we pivoted to restrategize. COVID-19 would have been enough of a challenge as we navigated the new normal of quarantine, social distancing, and Zoom meeting after Zoom meeting. Then came George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Dion Johnson, and Tony McDade. All Black people. All murdered by cops. Enough was finally enough. Communities across the country rose up to face down the dynamics of power, privilege, and race and demanded a new way of life. The resounding message was clear. The tools of oppression are too costly to ignore or sustain any longer.

COVID-19 made visible what those of us on the ground, community organizations and activists alike, have known for years. Prisons and jails are dangerously overcrowded, unhygienic, violent, and dehumanizing institutions. It wasn’t a question of if COVID-19 would spread through correctional facilities but when Jails and prisons are not designed for people, let alone for preventing the spread of a deadly virus. Social distancing is near physically impossible in an eight by six–foot cell crowded with people. Meals are mostly communal, with incarcerated people seated elbow to elbow. Personal protective equipment and cleaning supplies were also in short supply. Frequent handwashing is difficult when soap is not readily available. Most people on the inside are not provided with soap; they must buy it from the commissary. During COVID-19, correctional facilities simply didn’t have it. In many facilities, alcohol-based hand sanitizer is considered contraband.

Beyond that, incarcerated people, especially in local jails, cycle in and out; and correctional staff leave and return daily, often without screening. Testing was in short supply so it was hard to know exactly who did and did not have COVID-19.

When incarcerated people were tested and found to be positive, they were often sent to solitary confinement. In general, there was a lack of basic protection and conflicting information, not only about COVID-19 but also about how it was spread. Incarcerated people were left to die. This is especially alarming given that people in these facilities are more likely to be immunocompromised due to age, HIV/AIDS, or other chronic health issues.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a wake-up call about these conditions inside correctional facilities for many people, one which also drove us to reassess how we serve our communities. Our understanding of the work remains unchanged, but how we plan to achieve our vision of liberation has changed. We were forced to reorient and strategize, map out our resources and needs, and form new collectives.

Like many other community organizations, Black & Pink rallied behind our people. We raised rapid response funds and resources through crowdfunding, mutual aid networks, and emergency grants. This allowed us to put money on our incarcerated people’s books so they could purchase needed items.

We created networks of people inside, so that we could reach even more people. Bailing people out became a catch-22. If we got people out, where would they go? Couch surfing didn’t seem like a viable option given the stay-at-home orders and the call for social distancing. How would they get groceries or find employment? We were caught between getting our people free and providing them stable and affirming access to the care and community that is needed upon release from incarceration.

We banded together with other organizations to demand a reduction in dangerous overcrowding by releasing the elderly, those with HIV/AIDS, other immunocompromised people, individuals with less than eighteen months left on their sentence, and pretrial detainees. The risk of carefully releasing people was vastly outweighed by the risk of leaving everyone inside. We demanded that jails and prisons prioritize the health and safety of incarcerated individuals by providing them with free hygiene and cleaning products, allowing for more phone calls, as visitations were shut down, and providing free testing, screening, and treatment of COVID-19. Given that the majority of COVID-19 clusters were inside correctional facilities, it was only a matter of time before those of us on the outside were impacted as well. Protecting people considered the least among us would ultimately protect all of us.

Post-COVID-19, will be a rare moment of opportunity. The mere fact that correctional facilities across the country were releasing incarcerated people in droves signaled that perhaps just reforming prisons isn’t the answer. Maybe we shouldn’t be incarcerating this many people in the first place. Perhaps the time has come to listen to the wisdom of prison abolitionists like Mariame Kaba, Angela Davis, Patrisse Cullors, and Ruthie Wilson Gilmore.

It’s a much larger conversation to figure out just how millions of people got incarcerated in the first place and whether the prison system should be our answer. It’s about more than just decarcerating as many people as possible to stave off a deadly virus. People are not only sentenced to time. They are sentenced to a lifetime of stigma, rejection from job opportunity after job opportunity, unstable housing, and roadblocks to necessities. Most will end up impoverished and without connection to care or affirming support upon returning home. This is state-sanctioned violence, discrimination, and neglect, a death sentence far outpacing the effects of COVID-19. Many of these people will come home. They are still our friends, our neighbors, and part of our community. They deserve better. We’re all in this together.

We must act to take advantage of what might not have been possible prior to COVID-19. We know that there is no going back to normal or business as usual. Racism, homophobia, transphobia, misogyny, ageism, ableism, and other forms of oppression work together to keep people locked down and pushed out. Prison systems became our default, with a mentality of “by any means necessary.” It translated into a callous disregard for human life during a crisis. We must ask ourselves: Was our way of bringing people to “justice” always this way? Can we move beyond reforms to something more restorative, more transformative?

We can, and we are. For those of us organizing in prison abolition spaces, it comes down to how we relate to one another as a people and a community. The way our prison system relates to people now is through retribution. Harm occurs, but the people involved in it are not centered in the process. People cause harm and people experience harm, but the state steps in to remedy it. Those who experience harm are not valued or heard, nor are those who cause it allowed to be accountable in a way that makes sense for the people who experience it. Acting through retribution doesn’t allow for accountability or healing. The experience of harm is nuanced and complicated, because people are complex. Retribution is too simplistic a response to the breakdown in relationships that results from harm. Restoring these relationships through community support, active conversations, and inclusion offers a better solution.

COVID-19 offered a glimpse into this possibility. Even in the midst of the uncertainty and fear of a global pandemic, communities rallied around mutual aid practices, people sent one another care packages, handed out free weed, practiced physical social distancing with Zoom calls, and offered free self-care guidance like yoga practices and meditation, among other things. Unapologetic acts of love and service were happening before our governments stepped up.

Values of mutual aid and community care that organizations like ours and others have been advocating for and practicing took root in the everyday practices of communities. People figured out what safety looks like for themselves and determined their needs and how to meet them. Others in their community responded to these needs. People, whether they knew it or not, practiced transformative justice. A justice practice that is a Native way of life, and that, most recently, women of color, Black women in particular, drafted as an intentional blueprint to follow, was transforming communities across the country.

It became obvious that pain and violence are viruses themselves. Not only do they spread without corrective action, but, pointedly, punishment replicates the pain and violence. We have space for healing and meeting people where they are at home in our communities. We see them every day. Maybe we give a smile or a nod. Put people in cages, isolated and separated from communities, and we lose their humanity. We forget they too are worthy of respect and love. They too have inherent value. We must do better, folks—be better.

Transformative justice is about existing in a world centered on equity and access for all. It’s about taking stock of our current institutions and ways of relating to each other and recognizing the “isms” (racism, ableism, classism, sexism, etc.) and “ics” (misogynistic, transphobic, homophobic, etc.) are really just a hoarding of power and privilege. Transformative justice is about change and healing. It’s about having the courage to say: “I’m beautiful enough. Here are my resources, and here are my needs.” Transformative justice asks of us some tough questions, but they are questions that are already being interrogated. How can we exist together recognizing we are all complicated beings? How do we unpack conflict and harm? How do we shift ideas of power so everyone can have the things they need to empower themselves?

We keep trying. We keep failing. We keep figuring it out. Achieving liberation through transformative justice is a marathon, not a sprint.

Zephyr Williams (any/no pronouns) is the deputy director for Black & Pink. Their experiences with the system as a gender-liberated person have propelled him toward community building, addressing marginalization, and challenging our ideas of justice. Zephyr works to dismantle the oppressive systems that perpetuate violence on the trans and queer community through a transformative justice practice. Through this lens, we can reignite that spark of courage within each of us that fans our flames of embodied worthiness and love. None of us are free until all of us are free. In xyr spare time, Zephyr can be found curled up with a good book, analyzing natal charts, having a dance break, or traveling the trails.