The time it takes to buy it

Rax King on the film Anora

Today Rax King returns to write about the film Anora. Previously she wrote for Hell World about wanting and sobriety, expensive wedding traditions, the film Priscilla, Lana Del Rey's Born to Die, the band Creed, and her favorite Weezer songs

Help pay for our great contributors with a subscription if you can afford to please and thank you. Supporting independent media is good. I also have a few more free subscriptions to give out thanks to a couple generous readers so let me know if you want one.

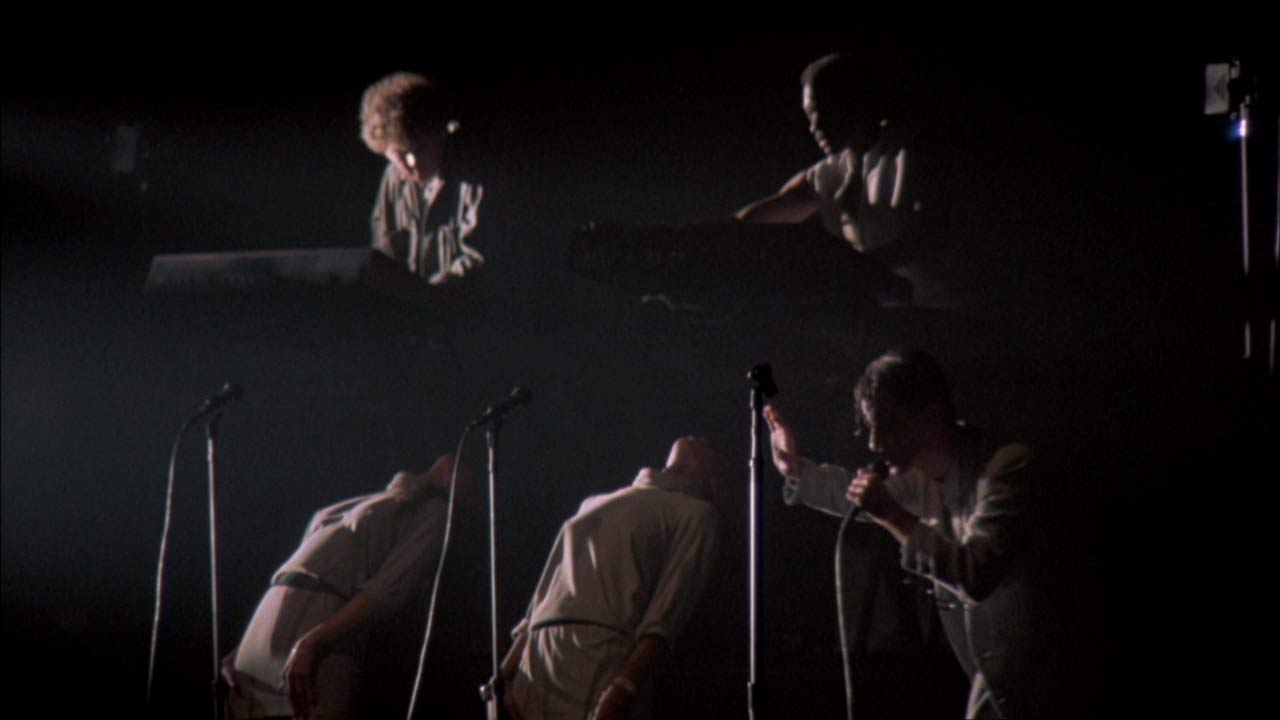

For more movie talk from Hell World, the premiere film criticism blog, happy 4oth to Stop Making Sense. Read Donald Borenstein unpack it in depth here.

When people talk about the uniquely filmic feel of Stop Making Sense, what they’re talking about, consciously or not, is the way this film uses light better than any filmed musical performance in human history. It creates a beautiful subconscious narrative flow between the tracks in a way that no interlude and no behind the scenes moment ever could. This is best felt in the transition between “What a Day That Was” and one of the greatest love songs ever written, “This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody).” The hard, infinite shadows give way to Byrne bathed in a single lamppost, a soft, dim, warm light that eventually starts to spread to the entire stage as he begins his iconic dance with the lamppost. It is an unmistakable shift in the mood. The anxiety never leaves the band’s sound – what is a Talking Heads song without it? – but the setlist for the remainder of the show feels and looks unmistakably looser from here.

Wealth rejects her

by Rax King

In Sean Baker’s Anora, the titular protagonist is a stripper whose name is, in fact, Ani—she tolerates being called Anora only on her passport, corrects anyone else who tries it. When we first meet her, she’s looking for customers who want to spend time in her strip club’s VIP room with her. Said customers tend to be the usual middle-aged men who can afford to pay the premium for private dances, which is to say they’re unattractive and tiresome, asking her how her family feels about her job. (“Does your family know you’re here?” she sweetly retorts to one such busybody. “I hope not!” he chirps back, too dumb and jolly to spot the dig.) Some of these men want a woman to be impressed with how hard they work, others simply want to feel her body moving against them. All of them seem relatively clear-eyed about the nature of the exchange taking place: a certain amount of money buys a certain amount of solicitous feminine attention.

Mikey Madison plays Ani with such cool, Brooklyn-accented panache that I could watch her walk men to the ATM forever, but before long a foil shows up in the form of 21-year-old Russian Ivan (a delightfully manic Mark Eydelshteyn). He’s looking for a stripper who knows Russian, though he speaks a little English; Ani, the granddaughter of a Russian immigrant herself, can understand his Russian but refuses to speak it. From the moment they meet, the two of them are always talking past each other, or mishearing each other, or speaking each native tongue in opposition to the other. She speaks to him while he’s focused on a video game; he speaks to her while her back is to him, her ass grinding his erection. A love is born, the sort of love that’s routinely born between stripper and customer no matter what Chris Rock once said about sex in the champagne room: a love that can only happen between two people who don’t know they will never understand each other.

I’m sure plenty of strippers have never fallen in big, irresponsible, week-long love with a customer, but I’m not one of them. Back when I was a stripper, I made great money playing the role of the most glamorous and adoring woman in the world, and I wanted most of my customers to agree that the exchange ended there, just like most of Ani’s do. But damned if there wasn’t a stubborn, needy little damsel crouching low in my spirit who believed that she might find the prince of her dreams in the VIP room. I wasn’t the only stripper cursed with such a traitorous inner damsel—the dressing room was forever abuzz with fairy tales of the girl who’d gotten swept off her feet, and into a mansion, by a besotted customer. She was always a few tantalizing degrees of separation away. She was a little like the mythical El Dorado of clubs that we always gossiped about, where the customers made it rain hundred dollar bills all day every day in some middle-of-nowhere dive whose name nobody could remember. The fairy tale girl probably existed in some form, but the point is that none of us actually knew her, and what we didn’t know we invented lavishly. Her marriage was perfect. Her husband thought she hung the moon. Seasoned strippers didn’t believe in her, but strippers like me, always half-looking for an excuse to indulge our romantic sides on the job, were members of her cult. Actually working at the club was a side quest to the main mission of finding a rich, handsome man to hang the moon for. That mission would require all our glamor and all our steely business acumen, and we’d be rewarded for the rest of our lives with first rate care from a man who would not be too old nor too ugly nor too bitter. If this sounds shallow and pathetic then I’d invite you to consider your secret fantasy about your own job, the best case scenario that you sort of know will never happen but keep striving for anyway because it makes your work feel less pointless. In my current work, that fantasy revolves around getting fan mail about my writing from Padma Lakshmi, who followed me on Twitter years ago and hasn’t interacted with me since. We all have dreams.

Ani gets to know Ivan, first in the club’s VIP room, then in his mansion where he pays her for speedy bouts of ebullient jackrabbit sex. The more time they spend together, the more fondly incredulous smiles she gives over his shoulder or behind his back, smiles that manage to imply every possible version of “is this really happening to me?” He’s callow and handsome and, it turns out, the heir to a serious family fortune back in Russia. His exuberance and youth are disarming. One senses that it’s a relief for Ani to have a devoted regular customer so close to her own age, considering the condescending middle-aged men who comprise a strip club’s primary customer base. When he offers her $10,000 to be his “horny American girlfriend” for the week, she nudges him up to $15,000. It’s the last good business decision we see her make. Her guard stays up only until he proposes to her on a whim in Las Vegas—well, until he clarifies that he’s not fucking with her, that the proposal is real. Her emotional surrender is immediate and observable. In a single remarkable facial expression, she converts him in her head from “generous regular customer” to “darling husband.” The Pretty Woman ending that she hardly dared to believe in is in sight.

It’s no spoiler to say that the two get married, nor to say Ivan’s parents (with the help of the family’s fixer Toros, played by a hilarious Karren Karagulian) are willing to do anything to have the marriage quietly annulled. The film becomes a larky comedy centered around Toros’ struggle to get both members of the happy couple in the same room so the annulment can be completed before Ivan’s furious parents touch down on American soil. Anora would still be a delight if it were only a larky comedy, but where it really shines, from this moment on, is in showing the inherent hostility of Ivan’s world to Ani—not the nightclubs and casinos of his American world, but the world of astronomical wealth and prestige that he stands to inherit from his parents, that Ani believed she could simply marry into. It rejects her like a failed organ transplant.

As Toros and his henchmen drag Ani all over Brighton Beach to search for Ivan, they cut vast swaths of destruction everywhere they go. They destroy a tow truck whose driver is rightly attempting to tow Toros’ illegally parked car; they smash up a candy store whose employees refuse to help them track Ivan down. Forced to accompany these men as they walk all over housekeepers and cooks, managers and gas station attendants, Ani is shown the dark undergrowth of her Cinderella fantasy. Ivan is not just the goofy, if spoiled and cowardly, rich kid she’s come to care for. He’s the direct beneficiary of exactly this sort of pushy, antisocial behavior, and if she’s able to convince him to defy his parents and stay married to her, she’ll end up treating working people the same way—working people like herself. She tries to stay game, but as the film goes on, we see her scowling through dusty windows or peering out from behind men’s backs while they exert these petty machinations of power. Visually speaking, she appears more and more frequently in states of retreat, withdrawal, no longer confident and choreographed and on top of a man with a G-string full of hundred dollar bills, but practically hiding.

In the years since quitting my last strip club, I’ve come to wonder how well the strippers who really do land wealthy VIPs of their own are able to assimilate, how well they make the transition from receiving the cash to controlling it and doling it out. It’s not a transition I ever considered, trying to harpoon whales in my state of romantic naivete. Oh, sure, I might fantasize now and then about having servants to boss around rather than bosses to serve, but would I have been capable of it in reality? To have those sorts of relationships long term means turning off, to a large extent, your capacity to be empathic and considerate. It means exchanging your decency for the fat wads of cash you push at people to compensate for your careless cruelty towards them. Early in the film, Ani and Ivan are snuggling on the sofa while Ivan’s housekeeper Klara vacuums. Ani notices the vacuum and lifts her feet out of its way; Ivan doesn’t, and doesn’t. Is it possible to marry into this lifestyle, become its doyenne, rule over Klara in the long term, and still be the sort of person who lifts her feet out of the path of the approaching vacuum cleaner? Out of the path of every proverbial vacuum cleaner, pushed by every working person whose job is to wait on you?

I can’t say that I pity the sorts of people who have $15,000 to blow on a week of paid puppy love, who play high stakes games with strippers’ hearts because their own desires are the only ones they can see. But after watching Anora I can say that I don’t envy them either. Those people have to permanently occupy a side of themselves that isn’t even available to most of us, with our concerns about making ends meet. For us, the Cinderella fantasy is special because we assume the wealth it stands to offer us will remain special once we have it. For them, nothing is ever special for longer than the time it takes to buy it.

Rax King is the James Beard award-nominated author of the essay collections Tacky: Love Letters to the Worst Culture We Have to Offer and the forthcoming Sloppy. She lives in Brooklyn with her toothless Pekingese.

Paid subscribers can keep reading below including some of the best things I read or listened to this week.