The paper had life to live

The reader response to this piece from the other day was so strong (like weirdly wildly strong) that I decided to take it out from behind the paywall for a couple days. Apparently it's "one of the good ones." While I do need to make money through subscriptions (hint) even more important to me than that is people praising me for my writing.

The next Hell World is going to be a top 5 songs thing like we did for Weezer and R.E.M. but this time it's Elliott Smith. Stay tuned for that Friday maybe.

Today Rick Paulas speaks with the folks behind Street Spirit – a Bay Area street newspaper written by and for the unhoused – about their efforts to get the longstanding but recently shuttered publication back up and running.

Before we get to that it's imperative that you pay attention to what's happening in Georgia this week. It's the most important story in the country right now.

Here are a couple of good rundowns from the Atlanta Press Collective here and The Appeal here.

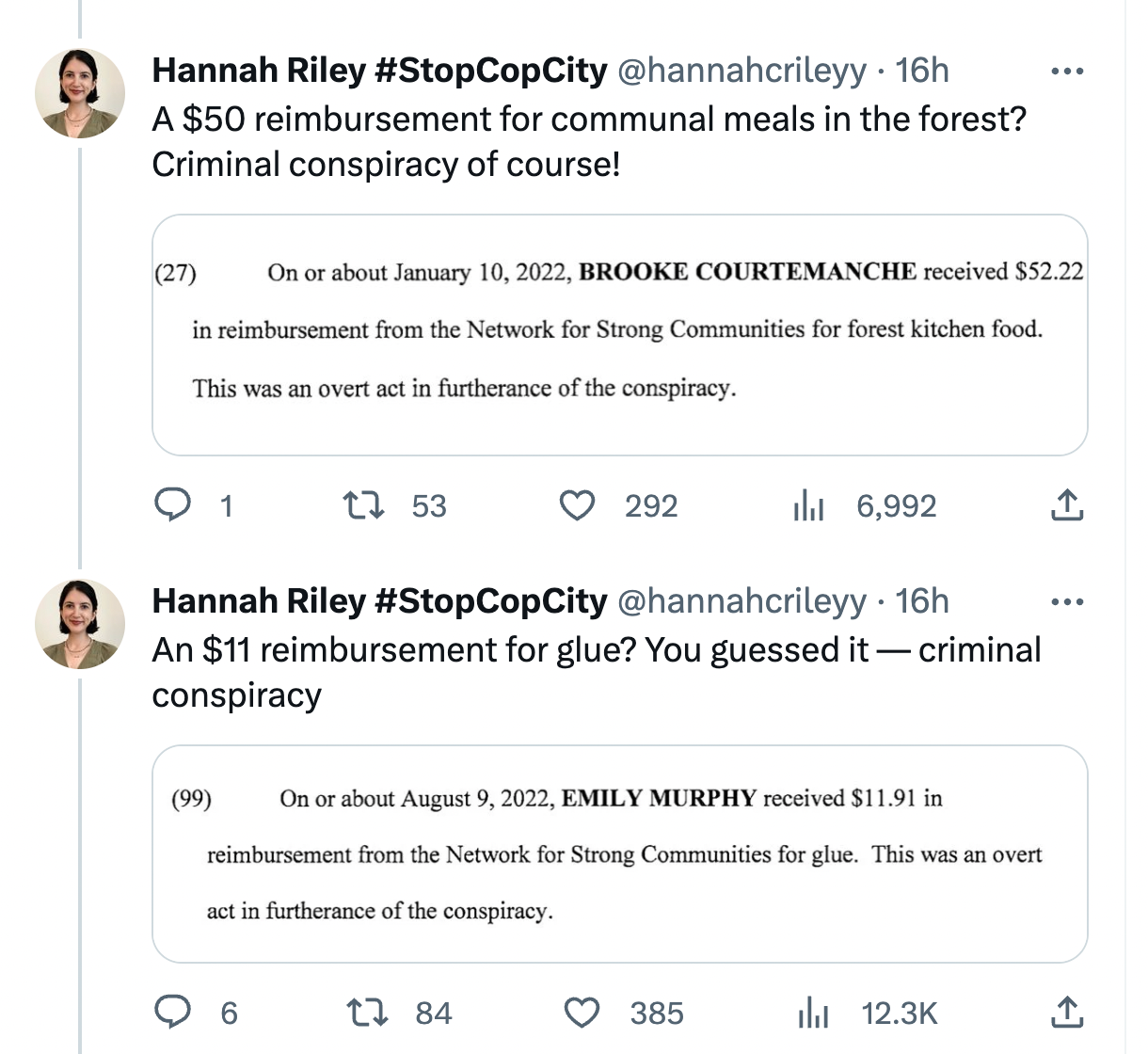

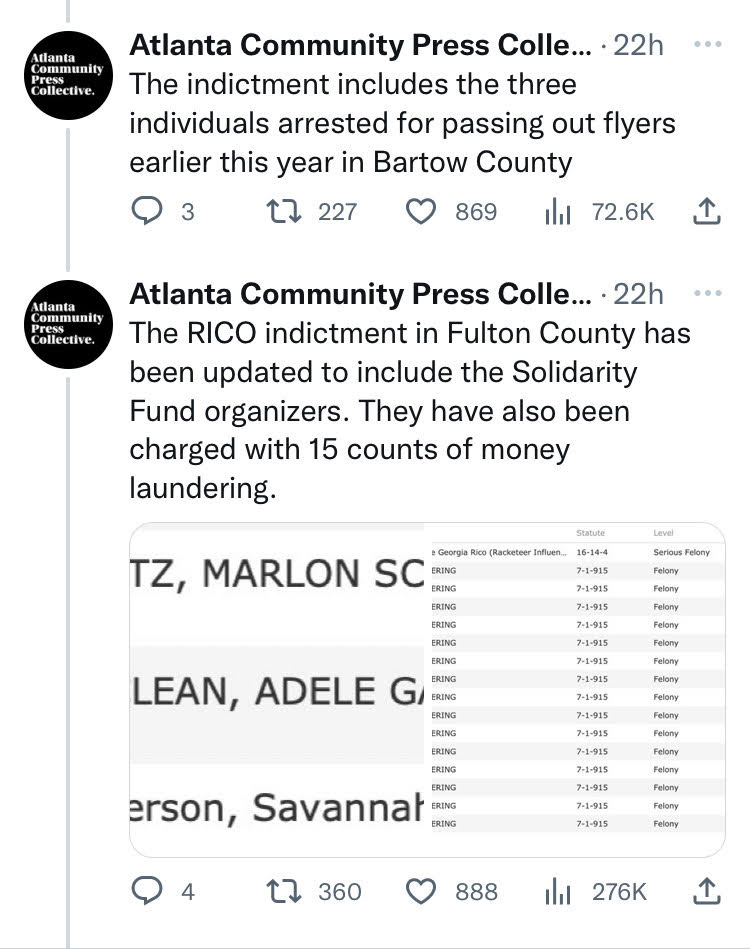

In short the Georgia AG has filed RICO charges against 61 members of a broad spectrum of disparate individuals and groups protesting the construction of Cop City in Atlanta. Among the charges in this attempt to paint peaceful protestors as part of a lawless anarchist group focused on overthrowing society as we know it (that's not really an exaggeration of how they are described in the indictment which you can read here) are acts so simple as handing out fliers or publishing zines or reimbursing other individuals for expenses for food and gas through mutual aid as if any of that were the same thing as purchasing weapons for a terrorist group or say conspiring to overthrow the United States government.

One person is being charged with furtherance of the conspiracy for writing his name down as ACAB when he was arrested.

Rather ominously the state has indicated the date of the beginning of the so-called conspiracy as being May 25, 2020 the day George Floyd was killed. That suggests they may look to roll up other protestors against police violence into this charade.

All together it's a shocking (although not really) assault on our civil liberties and an attempt to criminalize the act of protesting itself. And we can probably expect similar conspiracy type cases being brought against people who aid others in getting an abortion in the months to come.

For previous reporting on the effort to stop Cop City in Hell World see this peace about the arrest of the Atlanta Solidarity Fund on money laundering charges:

This piece on the arrest of a number of peaceful protestors:

And this one on the killing by police of Manuel Tortuguita Teran:

Earlier this week I went on the podcast Lights Out Mass to talk about the state of media in general, how I got my start in this rotten business, my collection of short stories, and my love of R.E.M. among other things. Give it a listen here.

Here's what I said in part:

Not to sound weird but I had been writing for a lot of prestigious publications and was kind of, you know, climbing the ladder a little bit. But I always ended up butting heads with somebody along the way, and either got fired from or quit basically every job I've ever had. Maybe I'm just a fucking asshole. I say this sort of thing a lot, but when there's two parties to a situation, often one of them is the one that's abusing and harming the other. I don't want to go to that guy and be like, what was your motivation for poisoning the river? You know? Or like, how do you feel about the fact that you just mowed down all the protesters in a car? There are good guys and bad guys. It became sophisticated somewhere along the way to think the world is gray, but very often it's not. Very often it's black and white. You see this with the New York Times lately, and their insistence on covering the issue of transgender healthcare. On one side we have people that want to just live their lives and get the healthcare they need, and they're not bothering anybody. On the other side, we have fucking genocidal assholes. And it's like, oh, well, we have to hear from both sides in order to work for a mainstream newspaper. That sort of thing... I don't know, I just don't want to do that. And I was lucky to figure out a space where it wouldn't have to.

A Street Newspaper Died and Is Coming Back

by Rick Paulas

The newspaper Street Spirit has been covering issues about and for those homeless in the East Bay of the San Francisco Bay Area since 1995. But perhaps more important than the contents is its distribution model: It is sold on the street by vendors who are unhoused or housing insecure.

Each month, vendors buy up copies of the paper—at 5 cents a copy, a dollar gets them 20—which they sell on the street to passersby, keeping any proceeds for the task. The suggested donation is $2 a copy, but often people give $5, $10, even $20. As you’d expect, this is not a moneymaker for publishers.

Until 2017 it was funded by the Quaker organization, the American Friends Service Committee. The Berkeley-based non-profit Youth Spirit Artworks took over until last June, when the board voted to cut funding. As word spread through the Bay Area that Street Spirit was dying, there was a slew of questions: What will happen to the paper? Where will the vendors go? Where can I give money to stop this?

Alastair Boone, the editor-in-chief since 2018, and Bradley Penner, who was to be her replacement, are embarking on a fundraising barnstorm to bring the paper back to life. I spoke with Boone and Penner about the end of the old and the beginning of the new.

If you are so inclined, donations to the effort to revive Street Spirit can be made here.

How did you each start working with Street Spirit?

Alastair Boone: I was 24 or 23 looking for work and saw on my college newspaper’s alumni page they were hiring. I was in D.C. at the time, and as soon as I saw it, I remember feeling, I don’t know, you know sometimes you meet someone or learn about an opportunity and are just filled with fire and energy? That’s how I felt. I knew this is going to change my life if I get the job.

Bradley Penner: At the age of 18, I left home as a transient youth, I guess in what you’d call crisis. I started hitchhiking and ended up in the Bay Area, and soon after that, Berkeley. I used to busk to make money and slept in the hills next to the quarter-mile track off Dwight. Upon first coming to South Side, I found a friend in front of Cafe Intermezzo with a stack of Street Spirits. Fast forward 15 years, and in that time I found a job and secured housing, and slowly figured out what I wanted to do, all the way to getting an MFA in Creative Writing from San Francisco State. I knew I wanted to move forward with editorial stuff more than writing poetry forever, but still wanted to remain linked to community and my neighborhood. I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do—taking a lot of menial editorial positions, not really finding a place which suited what I wanted to do—and I stumbled upon the job posting and immediately was like, oh shit, this is me.

What happened to the Street Spirit’s funding? Why did it get pulled?

AB: Street Spirit was funded by grants and donations given to Youth Spirit Artworks generally. I think because it was taken on in a moment of crisis, I don’t think the organization had capacity to do the legwork to find individual donors and grants and foundations specifically to support a street newspaper. Long story short, the board lost funding and Street Spirit was the first to go. They made that decision pretty abruptly. It was a big surprise when they told me that instead of hiring somebody they were going to close the newspaper.

What were the reactions from the vendors?

AB: People were upset. I think people didn’t understand because it’s so hard to imagine that Street Spirit would disappear. A lot of vendors have been with us since the 90s, so the idea that all of a sudden with no notice it was going to go away, it took a bit to sink in. We were lucky because Street Sheet, the San Francisco street newspaper, immediately agreed to print additional copies for our vendors to sell so they wouldn’t all of a sudden have no resource. A lot of our vendors depend on sales to survive, or to cover basic bills. But it’s been a slow burn. People are selling Street Sheet, and reading it, and getting to know it, and understand that something is shifting. In the months since Street Spirit went out of print, I’ve been hearing from people who miss having something to sell with local news stories—they don’t want to sell a San Francisco newspaper, they want to sell an East Bay newspaper.

BP: The regional quality of what’s inside Street Spirit makes a huge difference to those selling it. When I’m downtown I walk up to them and introduce myself as an incoming editor, and when they hear that, I’m met with excitement that there’s still this movement, but I’m also fielding a lot of questions. They’re selling Street Sheet, a San Francisco-based newspaper, so there’s a concern which is like, is this really speaking to my experience? There’s such a divide between San Francisco and Oakland, Berkeley, the rest of the East Bay, I feel like there is an inclination they want to be selling things that speak to their experience.

During one of our fundraising events, Derrick [one of the vendors] told the story of saving children on Piedmont Avenue from a potential kidnapping, and that created this relationship between the people who witnessed him who’d otherwise ignore him, not only as a person but a vital member of their community. And how that propelled his life, and what he sees as his worth within our larger East Bay community. To think there’s a risk of that going away just because we can’t secure funding is something that does not sit well with me. We’re brushing each other’s hands as we exchange cash and newspapers. To think that would cease to exist is not a possibility in my mind.

Brad, when you were selling it, what were you experiencing from people who’d come up to you?

BP: I wasn’t the one who was picking it up, that was my crew. I concentrated more on playing music. Busking for hours usually garnered a little bit of attention, but one thing I always noticed was if people were interested in Street Spirit there was an extra donation. They saw it as a kind of cultural transaction, as a commodity in a sense, this actual print newspaper. I found that people who’d purchase them would stick around longer than someone just listening to a song. Sometimes we’d sit and have conversations, not necessarily about the paper, but they knew what the paper represented, so it became this avenue for them to ask me about my story, things I’d experienced living on the streets.

Where did the idea of bringing Street Spirit back come from? Was this an automatic thing right away?

AB: I had been planning on leaving Street Spirit. I’d been there five years and was ready for something new. So when I got this news a month before I was supposed to leave, it was devastating. It just kind of broke me. I was so sad at the idea that Street Spirit would disappear after 28 years of providing this really vital, and in my opinion joyful, resource in the East Bay. To be honest, this isn’t a story where I found out this news and was like, “fuck yeah, here we go, finally there’s going to be independence and have all this control.” I was torn and overwhelmed, and didn’t know what to do. But slowly things started happening that made my decision clearer. Tons of people right away started donating, and within almost no time we’d raised $20,000. That money was helpful because it was like, okay, I could hire Brad, but more than the money, there were all these people who aren’t done with Street Spirit.

People were emailing, calling, getting in touch, wanting to let us know they want the paper to keep existing, they want to support by giving us money, or making artwork, or reaching out to say they want to host events. It was pretty clear to me that the paper wasn’t done existing. I wasn’t sure what I was going to do as an individual, but I knew that within a matter of weeks, the paper had life to live. I’d planned a trip to Italy because my cousin was getting married, and I was there for a few weeks, and when I got back, we had pretty much raised $80,000 without much work on my part.

So what does the future look like? I saw two fundraising events so far, what else is planned?

AB: We’ve had a lot of fun having events. Our first brought in a ton of money, like $8,000, and our second brought in less, like $2,000. Events are part of our plan moving forward, partly to stay within people’s minds and create environments where our supporters and vendors could come and have a good time. That’s really important to us. I’m also going to be cultivating more individual donors and foundations, applying for grants, doing those sorts of things.

Where are you at in terms of the goal and when do you think you’ll hit it? Do you think you’ll hit it?

AB: I definitely think we’ll hit it. There is so much money in the Bay Area, and so much specifically for employment support or jobs training or grassroots journalism. Like I said before, there are tons of people who’ve been reading Street Spirit for 20 years and have never had the opportunity to give, so I think we just have to create clear pathways for people. At this point we’ve raised close to $90,000, which is about a third of the way to our fundraising goal of $250,000 [to cover one year of the paper]. Our goal and hope is to start printing again in January.

Not that Youth Spirit Artworks was dominant editorially, but now that you’re free of any burdens, are you going to change it at all?

AB: I see this as an opportunity to re-envision the paper and its presence. Street Spirit as a newspaper that primarily covers homelessness in this region will stay the same, but there are so many opportunities we can tap into for it to be an exciting East Bay cultural document. Street Spirit is a newspaper that really prioritized space for visual art and publishing big, bright beautiful pieces of art, and I think there are a lot of collaborations we can do with artists in our community.

BP: Our events have been places where we’ve continued to build relationships in solidarity with the idea of collective struggle, and also with other groups doing ground work in the East Bay. Tenants unions, People’s Park, East Bay Food Not Bombs, Long Haul Infoshop, different musical groups tapped into what’s happening. As Alastair said, issues of the nonhoused community will always be the focal point, but in the Bay Area, right now more than ever there is this apparent class struggle happening to the point where most of us are a paycheck or two away from sleeping in a tent. Street Spirit can speak to the larger notion of what it means to live in the Bay Area right now. Whether you’re in a tent or rent-controlled apartment or not, this is a space for those things to coalesce. Whether that be working with tenants unions to let people know where their next meetings are, creating a resource guide with different mutual aid programs and harm-reduction services, arts coverage, basically trying to bridge connections between different patches of the larger East Bay community. There’s a lot to be said about the collective power of those who are housed and unhoused working together, so the big question moving forward is, how can we create space for those things to coexist collectively and in solidarity within the print medium.

If you are so inclined, donations to the effort to revive Street Spirit can be made here.

Rick Paulas is a writer in Brooklyn who made The Lady in Greenpoint, a 3-mile walking audio ghost story starting at the Pulaski Bridge, and The Palmer Hotel, a collection of spooky short stories set over a century in a downtown hotel, of which there are like 48 copies left for sale.

What the fuck are we doing here man. San Diego in the post below specifically but everywhere else I mean. Need to come up with a name for the place we currently live in.

There's been lot of "discourse" as they say after this tweet by Jeff Rosenstock from the other day.

Felt appropriate to post this on Labor Day. Here are the merch cuts being taken by the venues on this upcoming tour. This is going to cause us to sell our merch for higher prices than we'd like to at certain venues. We think that sucks. 1/ pic.twitter.com/FjSmhzs6Ki

— Jeff Rosenstock (@jeffrosenstock) September 4, 2023

He is right and righteous here.

If you never read it we covered this issue in here a while back.

Larry Fitzmaurice wrote:

When it comes to artist welfare the music industry is rotten to the core. It’s been decades since musicians have been able to make a decent living off of selling their work, and myriad factors—from new and emergent business practices and periods of economic downturn, to the ravages of the streaming era—have further made profitability a thing of the past. The issues musicians face when it comes to financially sustaining their careers have few prescriptive answers, but two words have frequently been used when it comes to what fans can do to support their faves: Buy merch.

“Most of the money we make comes from merch sales,” Weakened Friends vocalist/guitarist Sonia Sturino said when talking about the Portland, Maine-based rock band’s ability to generate cash while on the road. “I often joke that we’re a traveling T-shirt sales company posing as a band. We only break even or make a profit because of merch.”

Check out the appropriately titled new Jeff Rosenstock record HELLMODE and check out this great piece about it by our by Dan Ozzi.