The cops and local news won’t stop lying about fentanyl

Cops lie

Police lie. Constantly. If there’s any point at all I’ve managed to convey with this newsletter over the years I hope it is at least that. And they could not spread those lies so effectively without the help of the media and in particular local news who far too often consider themselves duly sworn deputies in the public relations branch of law enforcement.

Speaking of which you may have seen the latest entry in a long line of police lies about fentanyl. Here are some cops from Orange County, Florida dressed like they’re preparing to land on fucking Mars for the first time after maybe possibly coming into contact with some small amount of the stuff.

I guess dogs aren’t susceptible to it.

(Those guys aren’t to be confused with the cops in Orange County, California who have been embroiled in a massive scandal over their routine mishandling of evidence.)

This whole thing where cops are rushed to the hospital after touching some fentanyl is one of the more easily debunked lies among the many that they like to tell but no matter how many times doctors and scientists and some reporters explain that it is very unlikely to happen this way there will always be a new round of news stories contributing to the panic. That’s because the opposite of what I said about the news media thinking they’re cops also holds true: Cops think they are — and often act as — assignment editors for local news.

They might as well be the way their press releases are passed along without any pushback.

None of which is to say that fentanyl isn’t actually dangerous when used and (I know you know this) anyone out there using right now should be especially careful. It’s just that it quite simply does not attack you like a sentient alien molecule riding on the air from host body to host body as the cops would have us believe.

The reason they want us to believe it does is obvious to anyone reading this but just to lay it out anyway the more dangerous the job of a cop appears and the more that idea is laundered through the media the harder it becomes for people to push back against anything they say or do never mind get anywhere remotely near something like defunding them. After all look at how valiant they are out there risking their lives every day to rid the streets of the scourge of dangerous drugs. For us.

It also provides further justification for destroying the lives of the people they arrest for possession of said drugs. If people like this can use drugs this dangerous they must naturally be inhuman.

Our guest contributor today Zachary Siegel gets a lot more in depth on all this below. Siegel is a writer for Substance a newsletter about drugs and crime which you should check out.

If you missed this one the other day about how everyone’s drinking has been going check it out.

The cops and local news won’t stop lying about fentanyl

by Zachary Siegel

The first news clip I ever saw about a police officer who claimed to have overdosed on fentanyl just by touching it was almost four years ago, in May 2017. The harrowing story went national, then viral, because of course it did. But it started how most of these stories start: in the local news.

Under the headline, “Traffic Stop Almost Turns Deadly for ELO Officer,” Ohio’s Morning Journal portrayed a cop’s near brush with death after flicking a speck of powder off of his uniform after a routine traffic stop turned into a minor drug bust. A patrolman named Chris Green with the East Liverpool Police Department in Ohio was back at the station with his police buddies, amped up after taking drugs off the street, and giving some poor guys with a bad drug addiction a felony charge in the process.

Here’s officer Green’s recounting of his “overdose,” dutifully printed by local reporters and reprinted by national outlets:

“When I got to the scene, he was covered in it [fentanyl]. I patted him down, and that was the only time I didn’t wear gloves. Otherwise, I followed protocol,” Green said. Back at the station, one of Green’s buddies told him that he had something on his uniform. “Yeah, whatever,” Green said, casually dusting it off. Within a few minutes, Green said he “started talking weird. I slowly felt my body shutting down. I could hear them talking, but I couldn’t respond. I was in total shock. ‘No way I’m overdosing,’ I thought.”

By this point, the guy they arrested had told the cops he wasn’t feeling well, probably because he was going into withdrawal. That’s what often happens when you arrest somebody with an addiction, they get sick, because they’re suffering from a physical illness that in America is somehow considered both a brain disease and a crime at once.

The reporters then dramatize what happened next:

“Patrolman Rob Smith grabbed Green as he began to fall to the floor… and the ambulance crew already there for [the arrestee] began working on Green, quickly administering him a dose of the opioid antidote Narcan. Green described how his head felt “like it’s in a vice grip, my heart feels like I got kicked in the chest and my stomach feels like I have a case of the flu. I can’t wrap my head around [why anyone would take the drugs].”

Green went on to say that these drugs “are not only killing the people willing to shove it into their own veins, now they’re killing people like me and my family.”

Green’s boss, police chief John Lane, said Green was lucky “the effects” of the drug hit him in the station before he went home.

“If he would have been alone, he would have been dead. That’s how dangerous this stuff is. What if he went home and got it on his family members?”

“God was surely looking over me,” Green told the reporters.

Chief Lane then said, “It only takes one granule [of carfentanil] to kill an adult. These people (emphasis mine) have no regard for anybody, not themselves, not the police, not their kids. Their priority is not about anything but that next high.”

Wow, fuck off. These guys so openly loathe people who use drugs.

As I’ve written dozens of times, most recently for a newsletter I co-write called Substance, this whole supposed overdose incident is a chemical, biological, and physical impossibility. But that hasn’t stopped news outlets from keeping the myth alive.

This week has been a busy one on my particular beat.

In the last few days a prosecutor in Ohio allegedly overdosed after being “exposed” to a substance in a courtroom, just as cops in Florida had to call a hazmat team after finding fentanyl at a crime scene and they started feeling “dizzy.”

Days before these two bogus stories ran HBO’s John Oliver did an entire segment about harm reduction, and thoroughly debunked the “horseshit” notion floated by cops and repeated by news outlets everywhere, that fentanyl can kill you just by looking at it.

To understand how unreal all of this is, just listen to the supposed overdose symptoms of East Liverpool’s Green. He got the wind knocked out of him? His head was in a “vice grip”? He said it felt like he had the flu?

Sounds real as hell. That type of thing only happens if you’re in withdrawal, not when you’re overdosing.

Finally, he said he was “in shock,” which is probably the only true thing he said in the whole story. Because police have been told by their bosses and federal authorities for so many years that touching fentanyl will kill them. So here the guy went and touched it, then he got scared and panicked.

Cops are trained to feel threatened and use force if somebody near them makes any movements. They’re also trained to think fentanyl is as deadly as anthrax. In both cases the most important underlying message of any police training applies: You are in constant danger.

In reality fentanyl is indeed a potent synthetic opioid, but it only poses any danger to those who inject it, snort it, or smoke it, i.e. people who are buying it on the street and using it to stay well because they have no other choice, because all the pills and heroin are gone and all that’s left is this ungodly garbage cooked up in underground labs. Garbage that does, to be clear, kill tens of thousands of people every year. Just not the cops you see on the news who spent ten seconds in the general vicinity of it.

In journalism school, my professors told me to watch out for stories that are “too good to check.” Back then, as a naive nerd who wanted to be a Serious Science Writer, I thought that sounded insane. Who wouldn’t double and triple check what they’re told by sources? Especially when those sources are cops, an authority with a history of lying longer than a CVS receipt.

But it’s true, news outlets really will just say fuck it and run with anything the cops say.

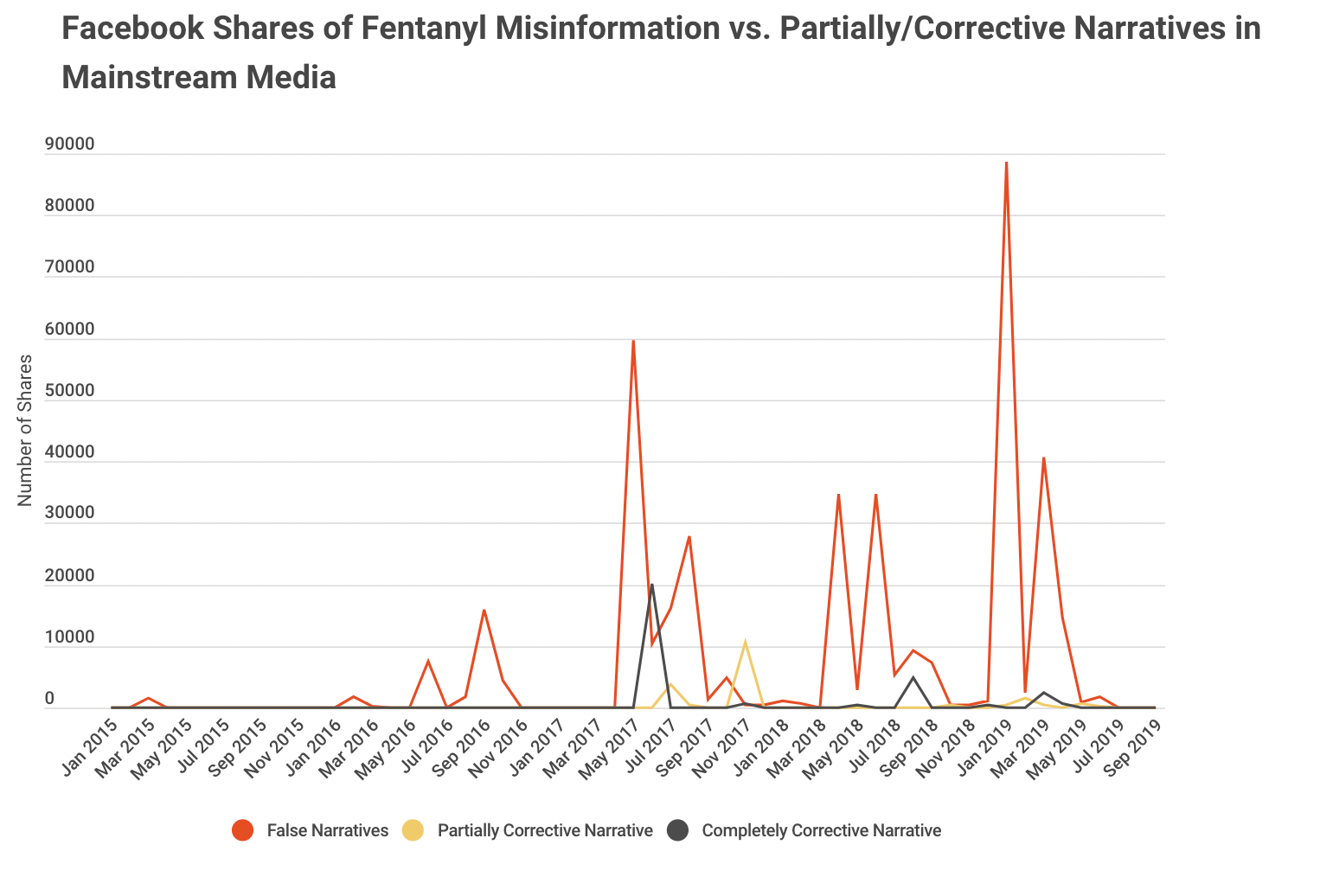

I’ve studied the anatomy of how these stories go viral, and have co-authored peer-reviewed journal articles that statistically illustrate the role local news and social media play. Analyzing social media shares for one study, we found between 2015 and 2019 that there were 551 news articles containing false information about fentanyl. On Facebook alone, these stories received more than 450,000 shares, reaching an estimated 70 million users. Making matters even worse, we saw that stories that added corrections were viewed significantly less than the original bogus story. We decided to publish all these results for free on a website we created called Changing The Narrative, a project aimed at helping reporters avoid making these kinds of mistakes.

Without bothering to consult any skeptical chemists or doctors or toxicologists — not even any users — national news outlets like CNN, CBS News, and The Washington Post blasted Chris Green’s story to millions of people.

Check those links, seriously. There’s no correction on any of them!

Hammering the nail in the coffin — and likely leading to my iminent premature death due to daily onset brain damage via whirlwinds of idiocy — the most listened to podcast, The Daily by the New York Times, had officer Green on the show to talk about how bad the opioid epidemic is in Ohio. What they really meant was how bad it is for cops like him.

It’s not just the press who spread this impossible unscientific story far and wide over and over again. Politicians can never resist either. Politicians like Ohio Senator Rob Portman, who used the incident to tout how his hawkish drug policies are going to solve the overdose crisis. There were roughly 70,000 overdose deaths in 2017. In 2020, there were more than 100,000 drug poisoning deaths. If Reefer Madness style propaganda were going to do anything to stem the tide, surely we’d have seen some progress by now.

It’s the year of our lord 2022 and these local news stories that paint cops as valiant heroes who risk their lives fighting the drug war are still being debunked every time they crop up. But Chris Green’s story was debunked all the way back in 2017, mostly by doctors and toxicologists on Twitter who a) know what fentanyl actually is and b) know how the drug actually works. Plenty of drug users also know right off the jump that these overdose stories are fake. If fentanyl was really deadly to the touch or somehow magically defied gravity and lingered in the air, people everywhere would be dropping like flies. And yet, it’s only cops who seem susceptible to fentanyl’s magical properties.

In 2018, my friend and harm reductionist Chad Sabora even taped himself pouring fentanyl on his bare skin to demonstrate that touching fentanyl is not deadly.

But bringing facts and science to a viral news story like this is like bringing a super soaker to put out a burning house. These stories go viral because the facts and science don’t matter. What matters is the story, perhaps the singular story that the entire political spectrum of the American mainstream media, which ranges from the right wing all the way to the slightly less right wing, can agree upon, which is this: Cops risk their lives every day to save drug users from addiction. And to save the rest of us from whatever they might do as a result of those addictions. Editors everywhere are more than happy to run with this line simply because it must be true that drugs are bad and cops are good.

As I wrote in Substance, a story so implausible is widely believed because it fits into already existing and deeply ingrained tropes and stereotypes about drugs in America:

The fear, the panic, can really only be understood through understanding the racist and dehumanizing history of drug policing. These fentanyl exposure stories are really stories about dehumanization, about courageous heroes and dangerous villains.

Cops are trained to feel threatened, and news stories like these reiterate how dangerous a threat drugs are. Not to drug users mind you, but rather to the brave cops fighting the drug war. The quotes from the Ohio cops in the story above illustrate my point to a tee. The one about drug users having no concern for the lives of anyone else in particular. You see, only dead-inside junky zombies would behave this way.

But get this. In 2019, a couple years after officer Green went viral and became Super Cop, the citizens of East Liverpool decided they were fed up with his shit, and they sued Green for being a lying, conniving officer of the law, high on power in the way so many abusers are. By 2021, officer Green was no longer employed. He was terminated by the East Liverpool Police Department.

A public records request revealed that Green had dozens of violations on his record, including “dishonesty, discourteous treatment of the public and gross misconduct.”

Cops like this lie regularly. They lie about everything. They’re lying to the public when it comes to these stories too.

Zachary Siegel is a freelance journalist covering drug policy and harm reduction. He co-writes the Substance newsletter with Tana Ganeva. His work has also been published in The Nation, The New Republic, Slate, New York Times Magazine, and elsewhere.