The collusion of the economic cartel of the NCAA

It’s like we’ve attached these deep emotional concepts of disgust and revulsion

Your support of my work is genuinely appreciated.

Today’s Hell World is about college athletes. Maybe you’re thinking hmm I don’t care about college sports all that much and that’s ok because I don’t either and I also happen to think it’s really fucking perverted to still care so much as an adult about the place you went to piss beer and half-read Jane Austen decades ago but that’s a whole other thing. Instead I follow a more respectable sport in the NFL but to be honest I think I might finally at long last have grown indifferent to it this year although I can’t tell if I’ve just become indifferent to almost everything else in life it’s hard to say.

One thing I do still care about and what you also care about if you are reading this newsletter is the exploitation of labor by powerful corporations colluding to artificially suppress wages in order to rake in billions of dollars off the backs of workers all the while convincing them and the rest of us that what they do doesn’t technically count as work anyway and on top of that telling them that doing all that labor for free is a rare privilege they should be grateful for.

“College sports, in a lot of ways, is an incredible funhouse mirror of so many of the Hell World pathologies in our larger economy and society,” Patrick Hruby a journalist who has covered the issue extensively for numerous publications over the years told me when we talked this week.

“The NCAA is running the exact same classification scam as Uber. If I tell you you’re not actually a worker, then you’re not entitled to the same rights and protections a worker is. That’s the whole ball game.”

Wait though aren’t the athletes given a “free education” you might be thinking. Don’t they get like $250,000 worth of tuition or whatever it is and the answer to that is lol no fuck you because going to college doesn’t cost $250,000 that is just a made up number that the colleges invented out of thin air. On top of that college athletes and in particular the ones that generate the most revenue for the schools barely have what most of the rest of us would recognize as a college experience. They might labor for free for forty hours a week outside of their classes which they aren’t really allowed to focus on all that much or even choose themselves anyway and their actions are policed in a way that most of us would riot over were we subjected to the same restrictions about how we can work to survive.

Sometimes I talk about how one guaranteed way you can tell if someone you are talking to is a piece of shit is to ask them whether or not they think college athletes should be paid. Another one is what they think about Colin Kaepernick. Bike lanes in cities is a good one too.

I spoke about the issue of payment for college athletes this week with Hruby whose newsletter Hreal Sports you should subscribe to along with Luke Bonner a former college and pro basketball player who co-founded the College Athletes Players Association and now runs Power Forward Sports Group a sports marketing consultancy. Among other things we touched on the law recently passed in California which The New York Times explained here:

Under the California measure, thousands of student-athletes in America’s most populous state will be allowed to promote products and companies, trading on their sports renown for the first time. And although the law applies only to California, it sets up the possibility that leaders in college sports will eventually have to choose between changing the rules for athletes nationwide or barring some of America’s sports powerhouses from competition.

We also talked about the made up and harmful mythology of “amateurism,” how collective action could transform college sports, and the fundamental injustice of the upward redistribution of wealth from workers to the bloated corrupt pigs who control the industry.

Before we get going a couple things to keep in mind if the general realm of college sports isn’t overly familiar to you.

From The Atlantic:

The NCAA reported $1.1 billion in revenue for its 2017 fiscal year. Most of that money comes from the Division I men’s-basketball tournament. In 2016, the NCAA extended its television agreement with CBS Sports and Turner Broadcasting through 2032—an $8.8 billion deal. About 30 Division I schools each bring in at least $100 million in athletic revenue every year. Almost all of these schools are majority white—in fact, black men make up only 2.4 percent of the total undergraduate population of the 65 schools in the so-called Power Five athletic conferences. Yet black men make up 55 percent of the football players in those conferences, and 56 percent of basketball players.

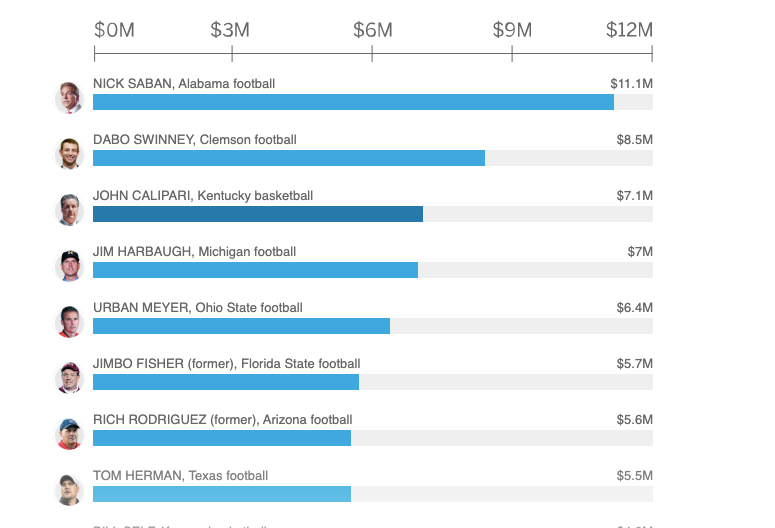

From ESPN:

In 2017, 39 of the 50 states' payrolls were topped by a football or men's basketball coach. That's not even including private institutions such as Duke or Stanford, where Coach K and David Shaw, respectively, would top North Carolina and California if they were public employees. And yes, if you look closely, some of the highest-paid coaches don't even work at those schools anymore -- looking at you, Jimbo Fisher!

Ok here we go.

Luke, you played in college. Is that when you started advocating for these issues regarding payment for college athletes?

I played at West Virginia and transferred to UMASS. I’m the youngest of three, my brother played at Florida, and played in the NBA for 11-12 years. My sister played at Stanford and Boston University. For me, I started to get exposed to it pretty young. My brother was valedictorian of his high school class and an All American basketball player, so it really set the standard impossibly high for me as the youngest. At Concord High School every valedictorian gets a $1,000 scholarship from the Rotary Club or something. He got that and used it for something school related, and NCAA compliance found out about it. They made my parents pay back the $1,000 or he was going to get suspended for basically an entire year from the team. It’s not like there’s anything you can do about it.

I remember being in middle school and seeing how stressful that was for my parents. My dad is a letter carrier for the Post Office, my mom is a teacher at an elementary school. Coming up with $1,000 isn’t super easy.

That was my first introduction where I was like What the fuck? There’s 14,000 people at every game, and he’s gotta pay this back, and his coach makes what?

I played and went through the whole system, and because I transferred I had to red shirt a year, and I ended up doing a sports management class, and I took classes on sports labor law and stuff like that, and realized how fucked up the system is. I got involved with the National Collegiate Players Association, which is a non-profit advocacy group, and eventually attempted to unionize the Northwestern football team. Now I shout into the void about the NCAA.

Patrick, you write and tweet about this stuff all the time. Why is it so important to you?

I’m not a former college athlete. I’m just a journalist. But I am someone who is very interested in Hell World. Even before you probably coined it, I’ve always been interested as a journalist in Hell Worldy things, and college sports, in a lot of ways, is an incredible funhouse mirror of so many of the Hell World pathologies in our larger economy and society. If you understand how the concentration of money and power at the top in all these various ways are able to exploit the people that actually do the work, that’s what’s happening in college sports. In college sports you have a system where people are chewed up and spit out. It’s an industry that is privatizing profit and socializing cost. An industry that goes to the government and gets tax breaks by saying their educational when it’s not that. An industry that takes advantage of having a lot of money and lawyers to hold off challenges to it in court, even though they’re breaking the laws that are supposed to protect people like college athletes.

There are so many ways in which it reflects all these problems that we’re dealing with, that in a weird way that’s why I find it so fascinating and why I write about it a lot. Sometimes it’s hard to go to someone and try to explain how the trends in this society toward monopoly and consolidation in business since the 1980s has drastically effected the economy and the entire world we all live in. But it’s not as hard to go to someone and explain: Hey all these schools get together, they make rules to keep all the money, and keep it away from the athletes who do the work. If you can understand that, it’s like: Hey, take a look. That’s what’s happening everywhere else too.

Luke, is it something you saw in your life and with your brother and sister, that when you play sports on a high level, or even not all that high, that there’s so much extra work you have to do to be a college student? Did you feel that burden in a way? I feel like a lot of people, especially the people Patrick fights with on Twitter, tend to think if you’re a college athlete your life is golden, you’ve got it made. It’s not like that though right?

That’s part of the stigma or the struggle, I’d say earlier on in this movement, that’s come pretty far in about a decade. The common person is like: Fuck you, I’d love to be the athlete on campus. That’s been one of the challenges to shift the narrative toward empathy for the athlete. … It’s essentially your job. When I was at UMASS and someone would ask me what I do I wouldn’t say I’m a business major or whatever, I’d say I play basketball. You’re on campus year round, and your life is super regimented and regulated. You’re a college student, but you’re submitting to drug tests, and you have to live within the confines of all these rules of the 300 page NCAA rulebook that you as the laborer and the product have zero say in creating.

A lot of people say it’s a free education, so the players aren’t paid, and I say, well, you are paid, it’s just illegally. Your competition is illegally suppressed through the collusion of the economic cartel of the NCAA. You provide the services. If you’re a Division 1 college basketball player, you’re doing around forty hours a week of basketball related activities on top of your academic schedule. You provide the services to the university and you’re compensated with your scholarship. But if you don’t go to your workouts you’re going to lose your scholarship, so it’s not a free fucking ride. Excuse my language.

There’s a lot of cursing here it’s ok!

BONNER: Basically, there’s pressure to perform. You aren’t a regular student. If a college kid goes out and gets drunk and does something stupid and ends up in the police log, generally people don’t notice. But if you’re an athlete it’s national news. And your services go beyond playing the game or practicing. You’re forced to participate in different marketing initiatives and community events and things like that, radio appearances. Eventually you learn, like, Holy cow, people get paid for these things? You have no idea. You’re like, yeah I’ll take some pizza. You think this is what I have to do because coach says I have to, and if I don’t I have to wake up in the morning and run twenty suicides.

What’s the “amateurism” argument. I know it’s horse shit, but why do people believe in it?

HRUBY: The thing that’s interesting about amateurism — and the fact that you call it horse shit is correct — is I think there’s an idea floating out there of some sort of ancient Greek ideal of competing for the sake of competing and enriching your spirit. The truth is, first of all, the ancient Greeks, they were not into amateurism at all. The closest translation for the concept is a word idiṓtēs which sounds remarkably like idiot in English. But if you go back and look at history, the ancient Olympians, if I was the champion, I would be showered with gifts. Just like you are now if you’re a great athlete…It was definitely something that we would be familiar with now with our professional athletes. They didn’t think athletes needed to be poor, or that there was some nobility in just competing.

You find this idea actually came to be in Victorian England. Essentially it was because the aristocratic upper class didn’t want to have to compete against dirty, soot-covered laborers, in rowing and other sports. They probably didn’t want to get their asses kicked by these guys either. Essentially it came out of the class system in England, like Oxford, they sort of adopted this system. Then our elite universities copied that idea and it made its way to Harvard and Yale.

If you look at the history of college sports in America, people were always getting paid. Either under the table or over the table. The whole enterprise, by the way, was student run. The schools only came into college football when they realized, oh my god, these guys are drawing all these fans, there’s so much interest, there’s money to be made. And if we control this we can control the money.

If you look at the history of the NCAA, go back to like the 1920s and up to today, the amateurism definition has always shifted. At one point athletes were able to get laundry money, then it got taken away. At one point schools were not allowed to give scholarships, that was considered a violation of amateurism. Then they decided because there was so much under the table payment going on they’d give them scholarships and nothing else. It’s just this long history of amateurism being whatever the NCAA says it is. There’s no real there there, and I think that’s really important for people to understand.

Your second question of why do we believe it is because there’s been a hundred plus years of propaganda and myth saying there’s something noble and pure about college athletes not being able to receive income beyond what universities give them. It’s really strange. If you talk to people who don’t really think about this much, look at the words they use to describe the economy of college sports. They’ll use words like that college team or player is dirty. If someone is getting paid they’ll literally say dirty. Or they’ll say clean. Think about that. It’s like we’ve attached these deep emotional concepts of disgust and revulsion to the very normal every day act of being paid for your labor or getting something in exchange for it. We don’t say that a professor or grad student in the lab that’s getting paid is dirty.

I do think there’s been this weird, almost unthinking cultural obsession with the idea that somehow college athletes are different than everyone else in society and that there should be special rules around their compensation that literally no one else in society has to abide by. It’s really weird if you step back and look at it that way.

There is a distinction, but in a way, this pressure from the NCAA and the rich universities trying to convince people that they don’t deserve their fair share of profits is very similar to what we do in a lot of other industries. It’s all pushing down the value of labor from the top, but in this case instead of being the next to nothing we pay most people, it’s literally nothing. We’ve got this pervasive myth that people who “flip burgers” of course don’t deserve more than $7 an hour. Is the thinking the same here? Just rich pricks trying to hold onto all the money?

BONNER: In sports there’s this privilege philosophy. Coaches always say it’s privilege to put on this jersey. There’s a rich tradition and all this stuff. You get sold on all that sort of thinking as an athlete. You’re on campus surrounded by all your fellow students who are racking up lots of debt. So as the player you don’t want to come across as ungrateful. You also factor in, at least in basketball and football, the revenue sports, the majority of the players are from lower income families. A lot of them are the first people in their family going to college even. So there’s a huge power dynamic that’s impossible to topple. You consider who is responsible for the best interest of the athlete in the system, and there’s really no entity that exists. The NCAA’s real duty is to — and I think this is in their bylaws, they spelled out the fiduciary duties of the NCAA Division 1 board of governors as to the member institutions and their administrations — so there’s really no one that has the best interest of the athlete in mind. It creates this massive power dynamic that’s pretty challenging.

When I first met Patrick I was in D.C. for what I later learned was lobbying. We were this ragtag group talking to people associated with different political positions. But we were going up against the NCAA’s full-time lobbyists.

HRUBY: Every school has lobbyists too, that’s an important point. Not just on the congressional federal level, but also in every state house. And these universities are usually the major institutions in their state. When it comes to the legislature they have all the power too.

BONNER: Patrick you mentioned the concept of amateurism is this fairy tale thing, always evolving, and even within my own family [it changed over time]. How it works when you’re a basketball player, at least on the high level, say you graduate from high school June 14, you’re generally on campus, starting to take summer classes the next weekend. You go right there. When my brother, who is five years older than me, was doing it, it was against NCAA rules for the scholarship to cover that session. I think he used his own money to pay for those courses. By the time I was in school it wasn’t anymore. And a few years after I’m out of school, and due to all the class action lawsuits, now it’s ok for college athletes to get paid a stipend that’s artificially capped at the cost of attendance level. $2,500 - $5,000 generally. And that would have been totally illegal before. And no one notices a difference in the product, so to speak, on the field.

The interesting thing to me is that the athletes who are hearing all of this talk about how we’re all in this together, this is a privilege, you’re representing the legacy of this school or whatever, the guys telling them this are making millions or hundreds of thousands of dollars a year, and they don’t give a shit about the students beyond how they can make themselves look good, right? Maybe some coaches care a little bit. Ultimately these are millionaires telling poor young people it’s a privilege to work for free. Is that fair?

BONNER: I would say there’s another layer to this too, which is the cyclical nature of the NCAA. It’s so short-lived. You’re in and you’re out and then there’s another eighteen year old going into the system. You don’t realize anything was messed up until you’re out in the real world. And by the time you realize it you can’t do anything about it. Your career is so short, it’s really challenging to rally an athlete to really, in a meaningful way, stand up against it. It’s not like you’re going to create some crazy movement and have a work stoppage, like when you’re in a career that you’re going to be doing for thirty years. Here you’re just going to be blackballed and that’s it.

HRUBY: Trying to build a labor movement with eighteen-twenty year olds… A lot of guys I talk to tell me it wasn’t until the end of their college career that they started to think about these issues. It’s not something you think about when you’re seventeen. When you get into the system maybe you start to think about it, maybe you take some classes that expose you to the ideas, or maybe you’re just thinking about the broader world because you wondering what happens after sports. And that’s when it’s too late.

That’s why you see a lot of the activists being people who used to be in college sports, who are a little bit older now, and have more experience with the world and what’s wrong. It makes it hard to build a movement from the labor itself. Having a strike would be very effective. Can you imagine if on the first week of March Madness half the team just didn’t come out of the locker room? Or they sat down five minutes into the first quarter and didn’t play? I’ve said this before, but everything would change over night. Even if just in the college football championship game the two teams came out and sat down on the 50 yard line and said we’re not playing until this changes. The reason I think a strike would be so effective in college sports is because the weak point for all these schools, and the NCAA now, is because they make so much money from the TV rights, they’re also completely dependent on that TV money. The networks do not care where the money goes once they pay it. They only care that they get the content they pay for. They want the games. They don’t care if all the money goes to the athletes and none of it goes to the coach or the athletic director. They’re the ones with the leverage. Even if the president of ESPN or NBC or whoever gets on the phone and says I don’t care what you do but we need games, so make sure there’s games, that’s what we’re paying you for. I really think that could change the system quickly.

Probably shouldn’t hold our breath for that.

But the risk is if it’s just one or two teams they could just get blackballed. The system could be like you’re out, screw you. It would be a lot more effective if all the teams did it at once during like the NCAA tournament. But that’s really hard to organize.

BONNER: Remember at Missouri a couple years ago there was a student on a hunger strike who wanted the university president fired for racist remarks? They just ignored it until the football team said we’re not playing on Saturday until they fire him, and within like five minutes the president was canned. It exemplifies the power that the athlete truly has.

To get back to the question about pressure for athletes, a lot of people like to say there’s only so many athletes that have value for a school. That’s entirely false. When I was at UMASS we made it to the NIT Championship. We weren’t even in the NCAA tournament. My coach went and got a $3 million per year contract at Oklahoma State the next season. UMASS had offered him like a million bucks a year at fucking UMASS. We built a $30 million practice facility. This is UMASS, not exactly a basketball powerhouse since the mid 1990s. So there’s definitely value there. The same guy that feeds you all the privilege language is gone the second there’s an offer on the table.

HRUBY: The idea that only a few athletes have value… If that were really true, then why does the NCAA have these rules in the first place, and why are they spending tens of millions of dollars in federal court defending it over the last decade? Why would you bother? Why would you have all these compliance officers on campus? Why would you pay all these people, and have this regulatory apparatus to enforce this rule, if it wasn’t necessary? As if only Zion Williamson and four other guys have any value? If that’s true, let’s get rid of it and find out.

Let’s say at some smaller school maybe a kid wants to endorse the local car wash or something like that, that’s what you’re talking about in terms of it’s not just the stars who have value?

HRUBY: For sure. If you look at all the college sports scandals, where someone was getting paid, whether it was a little or a lot, it’s not just the TV sports where you see this. You’ll see it in tennis, in Division 3 women’s basketball. One thing that’s been really eye opening to me in covering this issue, and talking to people about it, is how little people understand why they are paid what they are paid. Your value comes from solving someone’s problem. I do something for you and you give me money or something else in return. But it’s also a matter of is there competition for your service. This is where college sports Hell World reflects our bigger Hell World. The reason we have anti-trust laws is to ensure there is competition. When there’s competition for your labor then it’s more valuable. People have to competitively bid against each other. That’s the thing the NCAA and the schools are so afraid of. They don’t want to have to make competitive bids for the talent they need to win games. Every employer and industry in America would love that. Silicon Valley tried this. Apple and Google tried this and they got nailed by the Department of Justice when they tried to have no-poaching agreements between them. Turns out that’s illegal! One of the ways we protect labor and its value in this country is by preventing employers from colluding. That’s what the NCAA gets way with every day. I don’t think people understand that a lot of their own value comes from the idea that some other place can come along and offer you more.

Just because everybody doesn’t care about, let’s say, volleyball, it doesn’t mean there aren’t some colleges that really do, and they might be willing to bid on some talented player, right? Just because it’s not on TV all the time, maybe some booster at whatever college is really into volleyball, and they’re going to provide some money.

HRUBY: Absolutely. Look at how much money America spends on just youth sports stuff. During the recession, and the aftermath, spending on youth sports went from like $8 billion to $15 billion or something like that from 2007-2014. There’s a lot of desire to be good at sports in this country and to pay what it takes to be good. It doesn’t mean every college athlete is going to get a Nike deal. It might just be some rich alum wants to take the team out for a nice dinner after a game. It might be that someone is like you guys did great I got you all a team vacation. Or come by and sign autographs for an hour at my bar, and I’ll pay you out. It could be someone monetizing their YouTube channel.

BONNER: Another important thing is that schools like to say they lose money. In pro sports there’s this weird dynamic that the teams never want to show that they’re making money, because you need the public perception to be that you’re doing everything you can to win. In college every team is generally going to have a spending problem rather than a revenue problem. You’ll see these crazy facilities, ridiculous amounts of staffing. And it’s all to say hey guys we’re losing money, how can we pay you?

There’s also this wealth redistribution piece. That’s where I think this movement took hold when it was framed like a civil rights issue. Basically most of the money comes from basketball and football. If you look at the demographics of the players in those sports, it paints a picture. Essentially what you have is billions of dollars being made off the backs of predominantly black athletes. Then that money is redistributed to fund what some people like to refer to as the country club sports: the fencing team, the golf team. The exclusionary sports to begin with. You could never afford to play them unless you were a family of wealth. That’s fucked up too.

Can you explain what just happened in California?

BONNER: I’m a little conflicted. I think it’s good overall. But it’s also a little frightening to me. I think people are surprised by my stance on this. Essentially what happened is they passed a law barring universities from punishing a college athlete if they were to receive professional guidance from an agent, or receive money for someone leveraging their name, image, and likeness in some way. If Joe’s Carwash wants to pay me $500 to go sign some autographs, I’m allowed to do that now, in the year 2023. Beyond that, I could coach my own basketball team or camp. I couldn’t run my own basketball camp in college, or it just couldn’t say Luke Bonner on it anywhere. The intention is to free you up for that stuff.

Where it’s problematic to me is that there are still caps on things. The language is such that you’re not allowed to do endorsements that conflict with any team deals. If I’m going to UCLA, an Under Armour school, good luck getting a Puma deal. The other piece to this is that there’s still three years until this goes into effect. The governor has said he’s going to be in contact with the NCAA on implementing the rules, so there’s still NCAA power there. Personally I get wary about the political system being the bargaining unit for the athlete. Most politicians are pretty out of touch with the needs of these athletes. I always say there needs to be another collective bargaining unit that needs to exist for the athletes.

I do think there needs to be rules to cover this stuff, It just needs to be created in collaboration with the players.

HRUBY: It’s a small step in the right direction. To me the most encouraging part is not so much California, but that you’re starting to see a lot of movement in a bunch of state legislatures which could all together act as an accelerant. There are a couple of bills in the House right now. Interestingly, there’s a bill from Mark Walker who is a pretty Trumpy Republican out of North Carolina. Not necessarily who you would think of as caring about college athletes’ rights. He brought up the idea that we essentially have a system where it is predominantly African American athletes in the revenue sports generating the majority of the money, and they’re getting a very small slice of it that’s constrained by the rules of the system. And meanwhile the people that are running the system are overwhelmingly white, and they’re collecting all the money.

I wrote a long piece about that a couple of years ago for Vice called Four Years a Student-Athlete. We’re talking about, specifically for African American athletes, something like $2 million a year being stolen from them. If they had a free market and they got the same percentage cut that athletes in the NFL and NBA got that’s what they’re missing out on.

The point is, when I wrote that piece in 2016, the feedback I got was overwhelmingly from black people, like, thank you for writing this so it’s taken seriously, which is pretty sad, that a white guy had to write it to be taken seriously. But from white people a lot of the feedback was like how dare you compare this to slavery, or say there’s anything racial here at all? It was a nice preview of the “no, you’re the real racist” American Hell World of the Trump era.

Fast forward to 2019 and Republican and Democratic politicians are talking about this openly. Gavin Newsom talked about this. Mark Walker is talking about it. Matt Gaertz, the super-Trumpy congressman, actually tweeted in support of the California bill, basically like, yeah this is B.S. and old white guys shouldn’t be ripping off young black guys. So the climate has changed. That gives me a little bit of hope, long term. But getting to be allowed a limited use of your name and likeness shouldn’t be something a legislature has to provide for. The rest of us have that at all times.

The whole issue here ultimately is that college athletes should be treated under the laws like everybody else. Under the anti-trust laws, labor protections laws we already have.

People always ask me if you get rid of amateurism how are you going to replace it? Who’s going to decide who gets what? My answer is: Have you spent any time on a college campus? We already have labor and anti-trust laws. We already have a whole system for everybody else in society. It doesn’t always work great, but it works fine. We don’t need to replace amateurism with another set of hard controls. We can just have people negotiate freely. Maybe that means athletes across a sport or a conference or nationally form a union and do collective bargaining like in pro-sports. Maybe it happens in some conferences or sports and not others. I’ve never really been concerned so much that any particular athlete is getting a raw deal. What bothers me is the system. The system is fundamentally unfair and unjust.

BONNER: It’s pretty funny how so many conservatives, or people afraid of socialism, get bent out of shape at the idea of the starting quarterback making more than the tackle. How is that going to work!? I don’t know how does any business work?

HRUBY: I was at a debate a couple of years ago at the University of Texas. I was debating Jody Conradt, a legendary former basketball coach turned sports administrator – a good person by the way. And she turned to me and said How am I going to coach if my starting point guard is making more than my backup center? And I was like I don’t know, coach harder? That’s already the same situation on your staff. When you go back to review film with your staff, who are all paid differently, is everyone ready to stab each other? Grow up. That’s how the world works. That’s how every work place works.

BONNER: Right, how do you work with the assistant coaches that make a quarter of what you do? Even now, how things already are, when people are like what about the field hockey team? We’ll have to cut their sports?! Well look at it now. In high schools you have these state of the art locker rooms with like a barbershop and whatever else for the football team, and the girls’ soccer team doesn’t have that they can barely afford to travel to games.

What is the controversy around the term “student athlete”?

BONNER: It was a term that was invented by the NCAA to avoid having to pay workers’ compensation.

Last time I checked in the NCAA rulebook, I don’t think there’s even a requirement that schools have to cover the cost of an injury.

HRUBY: There’s not. As a college athlete you bring your own insurance to the table. They’re not under any obligation to cover your medical, and definitely not if you get a major injury. This is why the term student-athlete was invented. It was invented in the 1950s by the NCAA because they didn’t want to pay workers comp to the family of a dead college football player. Why it sticks around is because they want to classify all these people – again we treat college athletes like they’re this different class of people than everyone else – that’s what they are doing with the term. It’s a reflection of Hell World here. The NCAA is running the exact same classification scam as Uber. They have a hyphenated term of their own. “Partner-drivers.” If I tell you you’re not actually a worker, then you’re not entitled to the same rights and protections a worker is. That’s the whole ball game. They want you to think college athletes are not entitled to the same protections as everyone else is. Whether it’s labor, or anti-trust, pick whatever category you want. If I’m working in the stadium on Saturday at Michigan or Notre Dame and I’m selling beverages, and I get hurt on the job, I’m collecting worker’s comp. But if I get some horrible injury on the field, get a concussion or worse, or I blow out my knee, I’m not getting jack. I’m doing the most valuable labor in that building, but you’ve convinced everyone what I do isn’t labor because I’m a student athlete. It’s the exact same thing as Uber.