Stopping Cop City, the murder of Tortuguita, and the trees that got us here

Today we have some great on the ground reporting from the protests against "Cop City" in Atlanta. First a couple things from me. Pay to support independent journalism please and thank you.

Cops killed more people in 2022 than any year since we've counted. 1 in 47 adults in the country are under correctional supervision. We have 20% of the world's prisoners with 5% of the population. If shoplifting and fare jumping are a problem – as a number of freaks on the right and in the center would have us believe this week – it's not because we don't punish enough.

I'm sure this fucking nerd like many polite centrists considers their politics distinct from the likes of "let's cane gum chewers" like Matt Walsh but it's a distinction of degree not kind.

I think a lot of liberals underestimate how much this kind of behavior erodes the norms of social trust and solidarity that make societies work well. https://t.co/fxhedr8710

— Timothy B. Lee (@binarybits) January 25, 2023

“I ain’t paid for a train or a bus in three years," Helen Andrews of The American Conservative reports one of the fair jumpers she's been standing around very normally counting in DC recently (while making note of their race) told her. Writing dialogue can be hard so I appreciate how authentic sounding her choice of quote is here. Really immersive.

Not to mention how believable it is that someone would jump the turnstile then think wait let me go back and talk to some weird lady and confirm her priors real quick.

Sure there are some “broken windows” crimes that are shitty to deal with broadly speaking (not fare jumping) but if our choice is to summon the cops who are gonna either beat or murder or cage someone for doing them is it a wonder a lot of people say ah well what’re you gonna do and look the other way?

Watching elite media institutions gin up a moral panic about petty crime over the last year has been remarkable.

— Michael Hobbes (@RottenInDenmark) January 26, 2023

America has high levels of poverty and no safety net! Do people think we just have more people worthy of imprisonment here than other countries? https://t.co/2yHm0Wd4Pz

I said a lot of this on Twitter last night and in this piece from last week but here it is again.

The total number of police slayings across the country last year was at least 1,176 according to Mapping Police Violence. That's thirty one more than the year before and twenty four more than in 2020 the year when it seemed like maybe possibly hopefully things might start to change for the better. Remember that feeling?

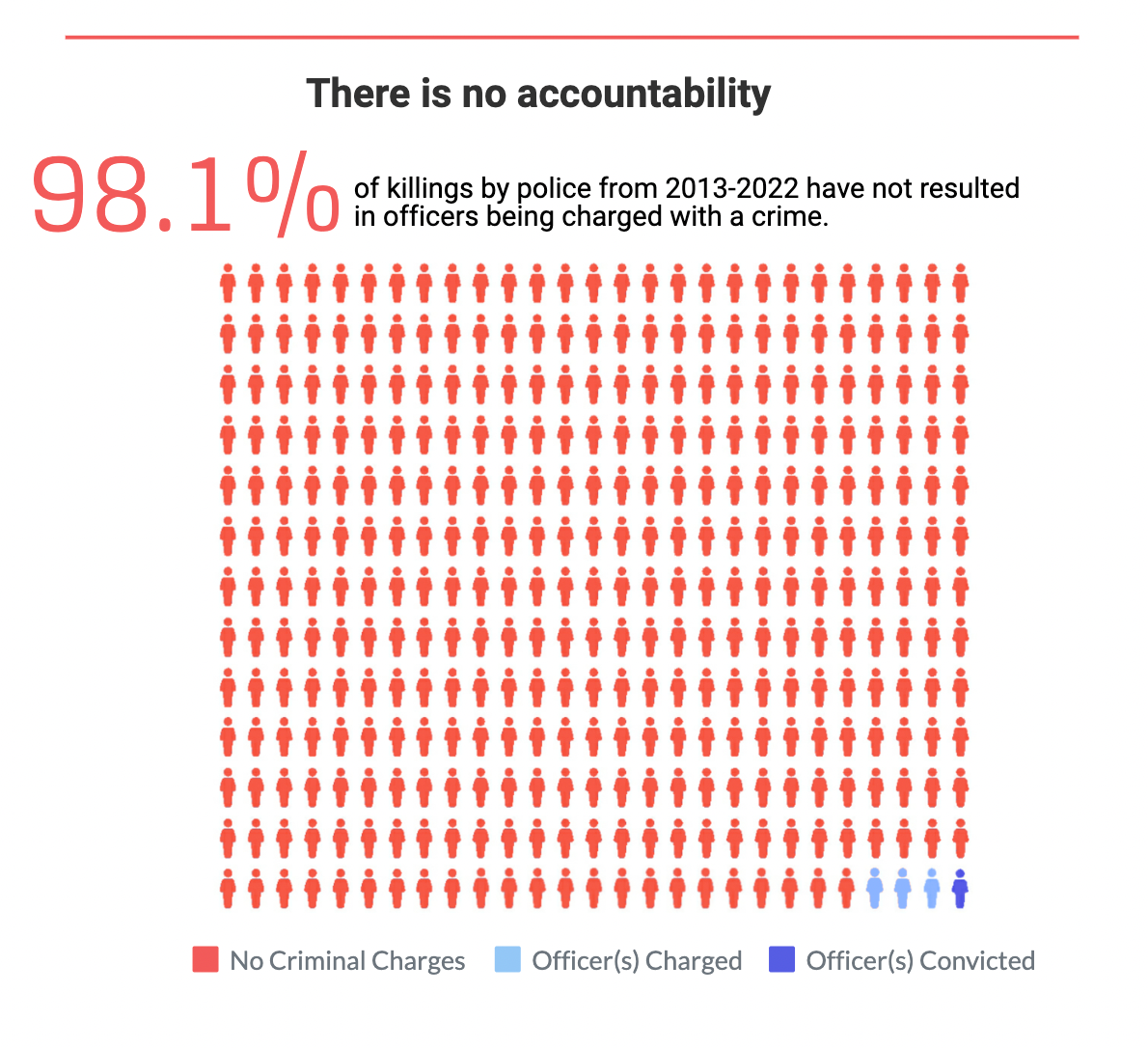

You will probably not be surprised to hear that almost none of these killers face any consequences.

If we're ladling out portions of blame for the "erosion of the social contract" or whatever I happen to think it might have a lot more to do with police killing and maiming and caging us with impunity more so than some kids hopping the turnstile but I'm not a punishment-obsessed ghoul so what do I know?

If you survey the state of things in the US today and think for one second wait are we not being punitive enough? I think you should probably contend with what an even crueler America might actually look like and decide if you're ok with that and then say a prayer to God for forgiveness.

This video here is one of the most downright evil things I've seen in a long time. This fucking guy has taken it upon himself to gleefully destroy the tent structure of an unhoused person on the streets of Los Angeles and film it for clout on the internet. It's shit like this that makes me believe in the second amendment and castle doctrine laws for a change. It's shit like this that makes me wish I actually believed in Hell. The real one I mean not the one we're already in.

When you are this type of guy you are making the same sadly correct gamble that every prolific serial killer in history makes which is that you can harm the homeless (and sex workers and trans people and other more vulnerable types) more freely because cops do not care what happens to them.

As it so happens those are the same classes of people that the cops themselves frequently abuse.

Somewhat related you might want to read this one if you missed it as the NYT is once again on their trans bullshit.

Every time I see some anti-trans article trying to hide behind concern for children, I think of what @lukeoneil47 said https://t.co/2OVaHfko75 pic.twitter.com/gavYUo6EeU

— Marc Masters 🌵 (@Marcissist) January 24, 2023

Stopping Cop City, the murder of Tortuguita, and the trees that got us here

by Rachel Garbus

The trees are still standing for now. Most of them at least. Acres and acres of trees, vertiginous loblolly pines and sprawling boxelder maples, here and there an oak, thicker than a tractor wheel, forking into two, three, four limbs that climb towards the canopy. On the banks of the South River and the creeks that feed it, river birch proliferates, long fingers reaching towards the thin winter sun.

Most of the trees in this fiercely contested Atlanta forest are still alive, but everywhere there are signs of death. Along Bouldercrest Road, dozens of acres have been clear-cut, exposing a raw swath of red Georgia soil. Barely a hundred yards into the forest, the limbs of a towering pine lie felled, oozing sap, so freshly cut their needles are still vividly green. And deeper within, close to the river, a small encampment of tents marks the place where a forest defender bled to death on the soil they’d been protecting.

Last week, Manuel Teran, a beloved forest activist known within the community as Tortuguita, was killed by a cop, shot during a multi-agency raid whose details are still widely disputed. Police, as a reminder, frequently lie with impunity. An officer was also shot during the raid, by a gun that Georgia Bureau of Investigation says Teran purchased last year; that officer survived.

Tortuguita’s death, appalling and unnecessary, was also the predictable result of months of violent escalation by police, whose hunger for a sprawling, 85-acre, $90 million “public safety” training center within the South River Forest has only hardened in the face of fierce public opposition. Since early December 2022, a joint task force comprised of GBI, the Atlanta Police Department, Georgia State Patrol, and several other agencies has waged a campaign to “eliminate the future Atlanta Public Safety Training Center of criminal activity.”

Using tear gas and pepper bullets to pull them from tree-sits, they’ve arrested and charged twelve forest defenders with domestic terrorism, a state offense with a 5-to-35-year sentence. What were once tidy communal forest encampments now lie bashed and broken, littered with slashed tents and tarps, smashed water tanks, severed climbing ropes. At the edge of the woods, protestors say, GBI is felling trees to create “demilitarized zones,” making it harder for forest defenders – or anyone, really – to walk between trees without being spotted by surveillance drones and helicopters.

This violence has not stopped the howl of protest against Cop City, which has become an international chorus united against environmental destruction, racial injustice, and state-sanctioned brutality. But these days, the police state is howling back, speaking in the only language it has ever known.

Building a new cop playground

The movement known variously as Stop Cop City and Defend the Atlanta Forest began in March 2021, when then-Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms quietly announced the creation of a new police and fire training center on 150 acres of city-owned land (after public outcry, the plan was later reduced to 85 acres, which is still bigger than the training centers for LAPD and NYPD combined). The city would lease the land to the Atlanta Police Foundation for $10 a year and contribute $30 million to the training center, while the Foundation privately raised the other $60 million, mostly through large contributions from major Atlanta-based corporations like Delta, Home Depot, Carter’s and UPS. APF President Dave Wilkinson promised the sprawling new complex would serve as “a beacon of 21st century policing.”

A “mock city for real world training,” APF’s plans include a model village to practice urban policing and crowd control tactics, a vehicle skills pad, a burn building, and a shooting range. According to documents obtained through open record requests by the Atlanta Press Collective, the center will also invite other police departments for “state-of-the-art” training: in a survey, the APF reported 43% of trainees will be from outside Georgia.

In other words, this is where the next-generation of the police state will sharpen its teeth.

The land in question is the former site of the notorious Atlanta Prison Farm, where incarcerated men, mostly Black and poor, were forced into agricultural labor for the better part of a century. Since the farm closed in the 1990s, the city has used the site as a dumping ground and – allegedly – as a place to bury dead Atlanta Zoo animals. The Atlanta Police Department has already been using it as a shooting range and explosives detonation site.

While it’s Atlanta city land, the forest where it’s located isn’t in Atlanta: it’s unincorporated Dekalb County, surrounded by communities that are majority Black and low-income. From the APF’s perspective, this was ideal, since wealthy white communities are the most likely to clamor for beefed-up policing, but loathe to cede precious green space to that endeavor. And since it’s outside city limits, no one in the surrounding neighborhoods has any representation on Atlanta City Council, which had sole discretion to approve the proposal.

“We have no one to represent us here,” said KD, who lives near the site in Gresham Park and helped organize community resistance. “If they had tried to build it within the city limits, there is at least some measure of community oversight.” ,

“This was really strategic by the Police Foundation,” she added

After realizing she’d have no voice in the political process, KD joined the Weelaunee Coalition, a loose organization of concerned neighbors, families and school groups united against Cop City. Welaunee is the traditional Muscogee (Creek) name for the river and surrounding forest, which is all part of unceded Muscogee territory; many movement members call the area the Weelaunee Forest.

After months of resistance, Atlanta City Council finally held a full public hearing on the proposal in September 2021. Over the course of 17 hours, more than a thousand citizens offered comment; over 70% opposed the project. Nevertheless, Atlanta City Council approved the proposal 10-4.

“It was the biggest show at a city council meeting they’d seen probably in decades,” KD said. “They still went ahead with Cop City knowing their constituents didn’t want it.”

City leadership, which is predominantly Black and overwhelmingly Democratic, have defended their actions, citing pressure to support law enforcement in a time of rising crime and dwindling recruitment. When it comes to policing, Atlanta leaders are guilty of the same about-face as their counterparts in other liberal cities, spouting reform rhetoric during the racial justice uprisings of 2020 only to kowtow to powerful police foundations and business interests.

And while nationwide a few progressive politicians have condemned the murder of an environmental activist (the first one killed in the U.S., it's worth noting), Georgia's own Democratic leadership has spoken out only to criticize the destruction of property during protests the night of January 21st.

None of it surprised veteran social justice organizers. “I give credit to Black Lives Matter and Movement for Black Lives (for creating) a small opening, at least in the conversation,” said Kamau Franklin, founder and executive director of Community Movement Builders, which has been organizing against Cop City since its inception. “But the capitalist state wants and needs the police to protect itself…I don’t think those tools will ever be disbanded without abolishing capitalism.”

Franklin immediately saw the training center for what it was: a gigantic, expensive consolation prize for cops in the wake of a nationwide uprising against them. “The real reason for Cop City was to give police a toy to play with, because (city leaders) wanted to make the police feel better about themselves,” Franklin said.

The Atlanta Police Foundation, it’s worth noting, doesn’t deny this. “It’s going to lift the morale and optimism of the police officers tenfold,” President Wilkerson told press in 2021. “It should pay for itself 10 times over.”

Defending an old forest

It wasn’t always going to be like this. Only five years ago, those same 350 acres of land were poised to be the lynchpin in a huge new public park, connecting public and privately-owned forest in a 1,200-acre system of trails, protected waterways, and pristine forest. A 2017 design plan by the Atlanta City Planning Department called the South River Forest one of the “lungs of the city,” and urged city leaders to protect the green space: “We’ll never have another chance to do this.”

Atlanta City Council agreed, adopting the design plan into the city charter. In 2018, community members formed the South River Forest Coalition to bring “the big idea” into fruition.

How did we get here instead? The South River Forest plan isn’t entirely dead, but corporate interests and self-serving government have all chipped away at the proposed public greenspace. In addition to the plans for Cop City – which required the Atlanta City Council to ignore their charter to approve – a large swath of forest was bought up by real estate developer and film producer Ryan Millsap, who once summed up his movie-making inspirations by musing to a reporter that “Americans are a culture of bad-asses.”

Millsap built Blackhall Studios, a parcel of sound stages near the South River Forest that he sold to a private equity group in 2021. Millsap still owns land in the forest, however: in 2020, Dekalb County approved a controversial land-swap, trading 40-odd acres of the county’s Intrenchment Creek Park for 53 acres owned by Millsap nearby.

Dekalb’s new land is supposed to become the new “Michelle Obama Park,” and Millsap’s company has promised to help finance it. But Millsap had already clear-cut dozens of acres of land, denuding the would-be park of trees. Intrenchment Creek Park, on the other hand, is a much-used 120-acre public park, with paved biking trails winding through the forest. Many forest defenders have been tree-sitting in this area, which has come to be known as Weelaunee People’s Park; living on public land requires less of a stealth operation than occupying the Cop City site. A gazebo in the parking lot became a grocery and meal distribution center on certain nights, and organizers have hosted numerous community events there and in the outdoor “Living Room” within the forest.

Many local residents opposed the land swap, and in 2021 the South River Forest Coalition and South River Watershed Alliance sued Dekalb County to block the trade. The park is supposed to remain open to the public while the lawsuit moves through court, but Millsap, who’s been openly disdainful of the Defend the Atlanta Forest movement, has used police pressure against protestors as a pretext for demolition. A few days after the GBI-led taskforce raided the forest in mid-December 2022, arresting six tree-sitters, a construction crew entered Weelaunee People’s Park. Under Millsap’s direction, the crew wrecked the gazebo, tore up a concrete pavilion, and destroyed a paved trailhead. The next day, the crew returned to take down several trees, including one that had hosted a tree-sit.

On a recent visit, the gutted gazebo lay upside down at the park entrance, next to a siren-red stop work order: after pressure from the lawsuit plaintiffs, Dekalb County had issued the order against Millsap. “It didn’t used to look like a warzone,” explained filmmaker and community journalist Nolan Huber-Rhoades, who led a handful of journalists on a tour of the woods. Amidst the rubble were colorful signs of resistance: someone had created a makeshift new patio out of shattered concrete slabs, and the rubble was dotted with cheerful paint. Two large slabs formed the base of a shrine honoring Tortuguita, with candles, cans of Modelo beer, and a green Beanie Baby turtle.

Despite the whiff of dystopia, locals were still coming through to bike and walk their dogs. That’s as it should be, Nolan said: “People in the movement still want people to hang out here, because this land is still – contestedly at least – public land and should be accessible to everyone.”

Deeper in the woods, forest defenders could still be seen slipping quietly through the trees. There’s no way to know how many people are still living out there. It’s always been a decentralized movement, and no one decides who should stay or go. Huber-Rhoades, who’s making a feature documentary about the movement with collaborator Lev Omelchenko, has been visiting the site since last year. They estimate there were over 50 forest dwellers at a high point over the summer, a number that’s likely dwindled with the recent police crackdown.

As we walked, GBI’s work was evident: every site of human habitation had been ransacked, with backpacks shaken out, chairs smashed, and limbs downed wherever a tree-sit once stood.

“The cops don’t want to bother taking everything out,” Huber-Rhoades explained, gesturing towards a kicked-in outhouse. “They just want to make it unusable.”

Even so, signs of life were everywhere, wrapped in that rebellious flavor of mirth activists often carry with them. A sign lay trampled under the leaf litter; turned right-side up, it read, “Everyone wants a revolution – no one wants to do the dishes.”

Escalating police tactics

The movement against Cop City, and the wider movement to Defend the Atlanta Forest, are built from broad, grassroots coalitions. They are comprised of toddlers and pre-school teachers, Muscogee (Creek) Nation tribal members, queer and trans folks, and concerned neighbors, as well as seasoned environmental activists and veterans of other protest movements. Even forest-dwelling defenders have no specific set of shared principles beyond a commitment to protecting the Weelaunee Forest, something Tortuguita, who was interviewed by several journalists before their murder, was quick to note.

“’Within the movement, there’s this constant struggle to avoid concentration of power, to disseminate decision-making,’” Tort told David Peisner for a recent piece in The Bitter Southerner.

While many coalition members are certainly non-violent, no centralized command enforces such a tactic across the movement. On the Defend the Atlanta Forest webpage, which operates anonymously, an FAQ asks whether the movement is violent: “Rather than get distracted by old tactical debates between violent and nonviolent methods,” reads the response, “Defend the Forest/Stop Cop City has grown by embracing a much simpler and more intuitive framework: defense and offense.”

That summation holds true. Opponents of Cop City have used every legal, political, and nonviolent tool available to them. At the same time, some protestors have destroyed or tagged construction vehicles, dismantled surveillance equipment, and thrown rocks towards police officers and construction crews. No one denies such acts took place, and organizers have cautioned against infighting over disparate approaches to forest defense. “They will use all tactics at hand to stop our movement,” Franklin told the crowd at a rally at the Dekalb County Courthouse in early January. “Do not allow anyone to limit the tactics at hand that will make our movement prevail.”

Would refraining from such tactics have made a difference? It’s doubtful. In October 2022, GBI used this petty vandalism as justification to escalate its militarized response to protestors, acknowledging the creation of the multi-agency taskforce. But by then, forest defenders’ success in stymying Cop City had thoroughly enraged the police, as well as city and state leadership. In July, an Atlanta city council member emailed Atlanta Police Foundation President Wilkinson. “Any progress from FBI/GBI/AG Office on hauling those terrorists in?” he asked.

Meanwhile, cop-friendly media has been beating the crackdown drum for months. Atlanta’s largest newspaper, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, has run multiple op-eds and editorials sensationalizing Atlanta’s crime rates and demanding the center be built; the AJC is owned by Cox Enterprises, whose CEO Alex Taylor has led fundraising efforts for the Atlanta Police Foundation. With corporate interests pushing for increased policing, and the rich white community of Buckhead in North Atlanta begging for a crackdown on everyone from unhoused people to kids selling water, cops were clearly game to find any reason to pull protesters from trees.

But if some busted-up trucks were a barely-there pretext to send in SWAT teams, they were far too skimpy to cover what came next. On December 13, after spending hours shooting tear gas and pepper bullets at tree-dwelling protestors, the GBI-led taskforce managed to nab five of them, hauling them to a Dekalb precinct where they were booked on multiple charges, including domestic terrorism. A sixth protestor was arrested the next day.

The domestic terrorism charges, which come with a minimum five-year sentence if convicted, have been roundly condemned by legal experts and human rights groups. “This is a political strategy to chill the movement,” Marlon Kautz, an organizer with Atlanta Solidarity Fund told me. The Solidarity Fund launched in 2015 to support protestors facing criminal prosecution. Through grassroots fundraising they’ve covered bond for those charged and connected them with attorneys.

“Nobody involved with this, including the police and prosecution, actually think that anyone did terrorism.”

The domestic terrorism charges stem from a statute adopted by the Georgia General Assembly in 2017. In a twist as depraved as it is ironic, the statute was passed in response to the Charleston church massacre in South Carolina, where a white supremacist killed nine Black parishioners; lawmakers wanted to give prosecutors more leeway to level terrorism charges for violent hate crimes.

The revised bill was so broad, Kautz said, that some legislators worried the statute could be used against all kinds of non-violent protests, like Black Lives Matter activists blocking a highway. “The response was that prosecutors simply wouldn’t do that,” Kautz said. “And here we are, six years later, with basically exactly that strategy being used by prosecutors.”

Since the December raids, the tone from the police, the city, and the state has shifted considerably. Governor Brian Kemp, riding high off his second-term victory, has vigorously defended the domestic terrorism charges, saying on Twitter that “They will not be the last.” In a rambling address to the training center advisory committee on December 15, Atlanta Police Department Assistant Chief Carven Tyus claimed that simply coming from out of state to protest is considered an act of terrorism. “Why is an individual from Los Angeles, California, concerned about a training facility being built in the state of Georgia?” he said, according to a local report. “That is why we consider that domestic terrorism.”

Perhaps even more alarmingly, Tyus boasted to the committee of using Georgia’s “hands-free” driving law to arrest a person who was filming police activity from their car during a raid. That’s very explicitly against the law and APD policy, Gerry Weber, senior attorney at the Southern Center for Human Rights told me. Weber has twice sued APD for interfering with citizens filming in public. “It’s very concerning that a second-in-command at APD is, in public places, lauding a pretextual stop of a person who is engaged in free speech activities,” Weber said.

With such steep escalation in militarized police tactics, the Stop Cop City movement was prepared for more SWAT-style raids. But no one was prepared for a protestor to end up dead.

Visions of another tomorrow

Cop City is a story about trees. And the trees, really, are the story of everything else. Atlanta is called the “City in the Forest,” but rampant development has imperiled the once-abundant tree canopy. A 2018 Georgia Tech study found the city was losing half an acre each day. The loss isn’t evenly distributed, of course: overlay a map of canopy loss with a map of Atlanta’s residential segregation, and you’ll find the fit astonishingly neat. Where the Police Foundation president lives, where the executives of Home Depot, Coca Cola, and Amazon live – those streets are dense with ancient oaks and magnolias. Where the heat islands are, the flooding exacerbated by soil erosion, the higher rates of asthma and the disappearance of biodiversity – those streets are dense with cops.

This story is about that.

The racialized boundaries of Atlanta’s tree loss make the South River Forest an even more extraordinary natural resource. It’s no coincidence that the “lung of the city” located in Black Atlanta is the one with lead in the soil, sewage in the water, bones in the ground. And yet it breathes. Not so long ago, there was a vision to preserve that lung for the people, but an organ of the state is always ripe for the harvest when a higher bidder comes around.

This story is about that, too.

It’s still not clear how a state trooper got shot and Tortuguita got murdered. It may never be. GBI has already changed their story, first saying there was no bodycam footage, later clarifying that there is bodycam footage, but only of the aftermath, and they won’t share it anyways. We don’t know the identities of any of the officers involved. Kautz said the Atlanta Solidarity Fund had connected Tort’s family with attorneys, who will help them explore the possibility of a wrongful death suit.

Some of the deep suspicion of the police narrative stems from Tort themselves: they spoke often about the power of nonviolence. “I don’t believe the state’s propagandistic rhetoric,” a friend of Tort’s and a fellow activist, who declined to use their name, told me. “Tort would never take someone else’s life into their own hands unless absolutely necessary for self or community defense.”

Their tent was on the Weelaunee People’s Park side of the forest, said Huber-Rhoades, an intentionally less aggressive stance than occupying Cop City land. “Tort was really a public face of this movement,” Huber-Rhoades said as we talked through the woods. “If they hadn’t been killed last week, they’d be giving you this tour.”

In the wake of Tort’s death, six more forest defenders were arrested, some for the same kind of vandalism that had been used to justify the initial raids. Every news outlet in the country caught the burning cop car that night; somehow they never manage to catch the free meal distribution nights, the poetry open mics, the toddlers drawing trees and suns in chalk with fat fists. Somehow they never manage to get into frame the way cops look at you when they really, truly hate you.

The police state has howled back. Domestic terrorism is a scary charge, not to mention the threat of death at their hands. But violence speaks only one language. In the week since Tort was murdered, their life has been honored all over the world, in all kinds of languages. This story is about them, too.

I never met Tort, but the friend who spoke with me sent me a voicemail Tort left them a few days before they were murdered. It was wrenching to hear their voice – bursting with life, edged with weariness, inflected with that insouciant mirth that the fighters of the fight learn to carry with them.

“I’m kind of in the wind,” Tort is saying. “But I’m doing alright. Hope you are, too.”

Rachel Garbus is a writer and editor based in Atlanta. She's the co-founder of Out Down South, a multimedia history project and podcast celebrating the stories of LGBTQ+ Southerners. She's on Twitter @rachel_garbus.