Prescription for Pain

One of the most notorious pill mill doctors of the opioid epidemic

What the fuck is China going to do to us that our own local, state, and federal government isn’t already willing and eager to do? Apologies to the might of the “Communist Chinese Party” but the average American is rightfully more scared of the dumb shit red-faced tribal sleeve second string high school football player sitting on his dick all day outside the 711 scrolling Instagram ass than they are of international spies.

Besides if they really wanted our private information they could just go and buy it from one of the many data brokers we have operating in this country.

Check out this scaremongering dog shit from 60 Minutes the very serious and sober journalism television program.

"Imagine you woke up tomorrow morning and you saw a news report that China had distributed 100 million sensors around the United States... That's precisely what TikTok is," Klon Kitchen, who worked in the U.S. intelligence community, said in 2020. https://t.co/BRA1zv8xLI pic.twitter.com/TRxSoR8fZ6

— 60 Minutes (@60Minutes) March 13, 2024

In the interview Klon Kitchen (lol) there says "The Chinese have fused their government and their industry together so that they cooperate to achieve the ends of the state" which is so fucked up because in the U.S. we do that too but to achieve the ends of industry (which is good by the way.)

Meanwhile here's what those cops I was just talking about are up to according to The Appeal.

A recent investigation by the New Jersey Comptroller revealed that at least 46 states have paid a for-profit training company called NJ Criminal Interdiction—which does business under the name “Street Cop”—to fill police officers’ heads with hateful rhetoric and bad legal advice. At a conference attended by more than 1,000 law enforcement officers from across the country, Street Cop trainers urged police officers to make unconstitutional traffic stops and indiscriminately shoot at those who defy their authority.

Moreover, Street Cop’s owner, Dennis Benigno, said that anyone who exercises their First Amendment right to record a police interaction should “get peppers prayed, fucking tased, windows broken out, motherfucker.” Street Cop also fed trainees a steady diet of racism and misogyny. Sergeant Scott Kivet likened a Black man to a monkey. Kivet also used a vulgar meme to make light of anal cavity searches, which are routinely used as pretexts for sexual and racialized violence. Another Street Cop instructor, Shawn Pardazi, joked about how he cosplays as Mexican and takes on names such as “Juan” and “Jose.” Pardazi also traded in Orientalist tropes, used a put-on accent, and invoked his Middle Eastern heritage as an excuse to objectify women and spew the kinds of “counter-terrorist” propaganda that fuels hate crimes.

Several instructors disparaged and dehumanized disabled people, used terms like “midget” and “retard,” and displayed offensive imagery. And when giving a speech about rendering medical aid, Sean Barnette, a trained medic and deputy sheriff from Oklahoma, advised fellow officers to treat criminal suspects like “live tissue labs” to “practice on.”

Street Cop instructors frequently objectified women, particularly sex workers and trafficking victims. For example, Nick Jerman gratuitously displayed photographs of women in lingerie, one of whom he described as a “human trafficking victim.” Similarly, Pardazi likened pursuing a suspect to an act of sexual conquest. He told fellow officers to act like “fucking gigolo[s]” going after “punani” and “whores.” Another trainer named Tim Kennedy bragged about “buying a bitch” during a counter-trafficking operation.

Today we have an excerpt from the forthcoming book Prescription for Pain: How a Once-Promising Doctor Became the "Pill Mill Killer" by Philip Eil. The book is a fascinating and extremely Hell World-appropriate look into Paul Volkman – one of the most notorious pill mill doctors of the opioid epidemic – and is the culmination of over a decade of work by Eil.

Before we get to that check out this story. Is this a metaphor for anything?

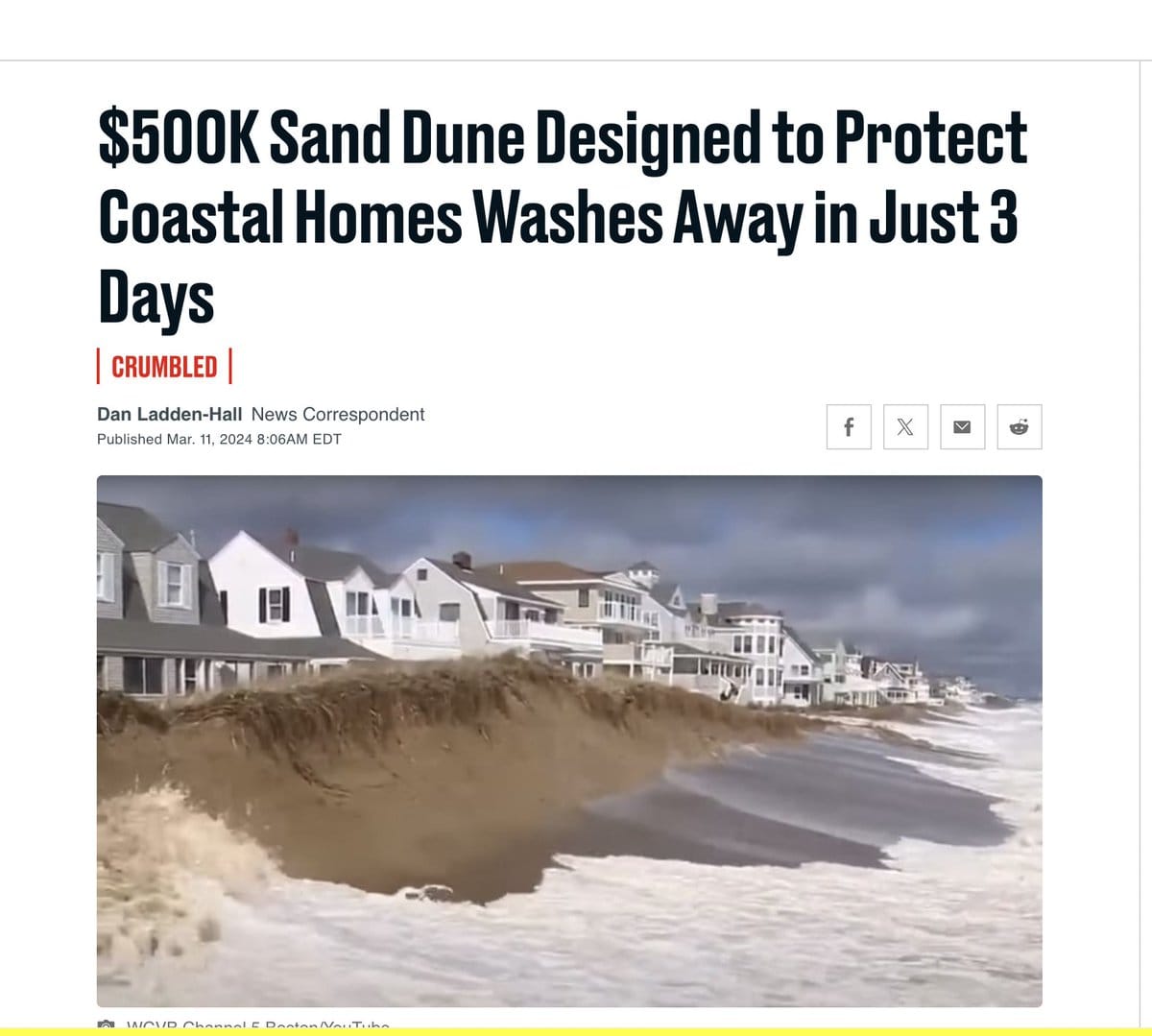

In a drastic attempt to protect their beachfront homes, residents in Salisbury, Massachusetts, invested $500,000 in a sand dune to defend against encroaching tides. After being completed last week, the barrier made from 14,000 tons of sand lasted just 72 hours before it was completely washed away, according to WCVB.

Good old sand. The one thing the ocean will never erode.

That said my sense of schadenfreude for beachfront property owners in Massachusetts eating shit is conflicting with my fears about climate disaster here. Much to reflect on.

I just had to write a very stupid check to pay my taxes – I love to do my part to support the Never Ending Death Machine. My accountant kept insisting that I can't write off cartons of Camel Blues as office supplies despite how crucial they are to my writing process so it was a bigger hit than I had anticipated. If you feel like subscribing to Hell World here's a stupid discount – 40% off! – that I will leave up for another day or so before I come to regret it. Your support is appreciated.

Here's some good news!

"A police consultant who examined the actions of Uvalde police during the Robb Elementary School massacre said Thursday that local officers were not to blame for the confused law enforcement response and the heavy loss of life," the San Antonio Express-News reported.

The consultant also determined that the police officers acted that day "in good faith" so that is a relief to hear. That they did all of that nothing by the book.

Seriously though here is some actual good news.

WBUR:

In a move she described as "nation-leading" in scope and ambition, Gov. Maura Healey on Wednesday unveiled plans to pardon all people convicted of simple marijuana possession in Massachusetts.

If approved, the pardon would forgive all state court misdemeanor convictions for possession of marijuana before March 13, 2024. It would not apply to charges of distribution, trafficking, or operating a motor vehicle under the influence.

Healey's office said the pardon could affect "hundreds of thousands" of people in Massachusetts, though the exact number is unknown.

Did you miss this piece from the other day about The Zone of Interest and Jonathan Glazer's speech at the Oscars?

I keep thinking about how Glazer’s hands were shaking. Like he knew saying something even as relatively measured, but still necessary, as he did was of course going to get him dragged to hell. And so he has been.

Alright here's Philip Eil with an introduction to his book excerpt. More from me down below.

In 2015, Luke interviewed me for an Esquire piece called Why Is the DEA Not Cooperating with This FOIA Request? In that conversation, we spoke about my efforts to report on my father’s med-school classmate, Paul Volkman, who was convicted in 2011 of a massive prescription drug-dealing scheme in Appalachian Ohio. My work on the story was at an impasse: the Drug Enforcement Administration – the federal agency that had investigated Volkman – refused to release thousands of pages of documents that were submitted as evidence during Volkman’s two-month criminal trial.

Thanks to the Rhode Island ACLU, two pro bono attorneys, and a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit, I eventually broke through that roadblock. And using the materials I received, plus a decade’s worth of other reporting, I have at last finished my book. It’s called Prescription for Pain: How a Once-Promising Doctor Became the "Pill Mill Killer" It comes out next month.

Volkman’s crimes took place over a nearly three-year period in the mid-2000s, after a series of malpractice cases from his years as a pediatrician and emergency-room doctor rendered him unable to obtain malpractice insurance and desperate for work. In early 2003, he accepted a job at a cash-only pain clinic in Ohio that required no insurance coverage.

This excerpt describes one of the strangest, most disturbing moments during the years that followed. In September 2005, Volkman parted ways with Denise Huffman, the owner of the clinic that first hired him. (Huffman, who had no college degree or formal medical training, later pleaded guilty for her role in the drug-dealing scheme.) And, for a few chaotic weeks, Volkman attempted to run a pain clinic out of an unmarked house on a quiet residential street in Portsmouth, Ohio, a sleepy town of 20,000 on the banks of the Ohio River.

Volkman would later be indicted, convicted, and sentenced to four consecutive life terms in prison – one of the longest sentences for any doctor convicted of opiate-related crimes. Though, to this day, he maintains his innocence. In a 2023 legal filing from prison, he wrote, “I was practicing good, proper and legal medicine…I was not then, nor am I now, a criminal.”

The House on Center Street

During his time in Portsmouth, Paul Volkman rented an apartment on the first floor of a house in a quiet, residential part of town. The address was 1310 Center Street.

“Center Street” is, in fact, not at the center of anything in Portsmouth. The one-block street is located about a mile and a half from the downtown business district, and the street itself is only about two hundred yards long. Like some of Portsmouth’s less-trafficked streets, it remains paved with red brick, which makes it a throwback to the days when all the city’s streets were paved that way. Car tires rolling on those bricks made a moist, rubbery rumbling sound. During Volkman’s trial, a former investigator with the Portsmouth Police described it as “a low-income area of our town” with quite a few vacant houses.

At one point, in 2003, Volkman wrote to a friend that when he was in Portsmouth, he “essentially never go[es] out except to and from the clinic.” So for the first two and a half years that he had commuted to town, the Center Street house was simply a modest place where Volkman slept when he was in town.

But in the days after his split from Denise Huffman, this changed. For a few weeks — in the most bizarre chapter of his tenure in pain management — Volkman attempted to run a pain clinic out of this house.

In the days following his split from Tri-State, he outfitted the apartment with phones, fax machines, and filing cabinets. He transformed the living room into a waiting room, complete with folding chairs. The kitchen was turned into a business office; a first-floor bedroom was converted into an exam room. He would later say that the house’s interior was arranged in “quite a respectable manner regardless of how the neighborhood and the outside of the house looked.”

The house never had any kind of sign indicating that it was now a medical facility. Although, later, prosecutors did submit as evidence a handwritten note that was affixed to the front porch. The page read: please use back yard to wait.

#

Like many aspects of Volkman’s case, the exact nature of what happened at 1310 Center Street is disputed in legal filings, trial testimony, and elsewhere. But all parties involved seem to agree on some basic facts.

By Volkman’s own admission, the Center Street clinic was, like Tri-State Healthcare, a cash-only operation with office visit fees of around $150. And by his own account, at around eight o’clock on the first morning of operation — Monday, September 12, 2005 — there was a crowd of over a hundred people on hand to fill out patient-intake paperwork.

The clinic’s first day of business also marked the start of a series of complaints to Portsmouth police. According to law enforcement documents, the first call that police received was from a neighbor who was alarmed by a jump in the number of cars parked on the street. Two days later, another call described the house as a “pill mill.” On September 26, two weeks after the clinic opened, yet another tip informed police that, at ten thirty that morning, there were seventeen people on the front porch waiting to see the doctor. One resident of Center Street later told the Portsmouth Daily Times, “A lot of neighbors are mad around here.”

One of those neighbors was Sammie Ishmael, who lived directly next door to Volkman’s house. She later described to me the dramatic changes that took place on Center Street after the clinic opened. As she told it, cars with license plates from Kentucky and West Virginia started appearing on the street. Crowds of people moved in and out of the house, spilling out into the backyard, the front porch, and the sidewalk in front of her house. One day she saw a van sitting in front of her house filled with people. It was hot that day, and a passenger door of the car was open; inside, a woman was knitting. On other days, she returned home to find clusters of cigarette butts and greasy fast-food wrappers strewn across her front yard and walkway.

Ishmael told me that people came to the clinic at all hours of the day. And because there was no sign on the house identifying it as a clinic, some visitors mistakenly came to her house. She told me that she had knocks on her door at 5 and 6 a.m. from patients asking to see the doctor. She said that these people had slurred speech and dazed eyes.

After a few weeks, she was livid. She had complained constantly to the police, but had seen no major changes to the operation next door. She had also tried speaking with Volkman. During one conversation, he had told her that the house was his new office and that he was in the process of obtaining a license to operate there.

Years later — and still clearly incredulous about the exchange — she recalled what she said in response.

“No, you aren’t in [the] process to get your license there,” she told him. “You need to take your doctor’s office and take it to Chicago and put it in your neighborhood.”

#

Inside the house, the clinic hummed with activity.

According to Volkman, he was seeing “about 35” patients there a day, with business starting about 8 a.m. and often continuing until 10 or 11 p.m. And based on his own numbers — thirty-five patients per day, paying $150 per visit — he was bringing in approximately $5,250 per day, which added up to over $25,000 per week. Without the Huffmans running the operation, the clinic’s profits now went directly to him.

But despite the brisk business, Volkman had a problem: Leaving Tri-State meant leaving the on-site dispensary, which meant that he was once again reliant on pharmacies to fill his prescriptions. And given how many local pharmacists had previously refused to fill his scripts, there was no obvious solution.

Legal records indicate that at this time, one of Volkman’s patients, identified only by the initials D.S. in the records, helped to solve it. This patient apparently searched online for pharmacies in the area and made phone calls asking if they would fill scripts for oxycodone, hydrocodone, Xanax, and Soma in the dosages Volkman was prescribing. An unknown number of pharmacies said no; they told the caller that they either didn’t have the meds in stock, or weren’t comfortable with the prescriptions. But one pharmacist agreed to the terms. His name was Harold Eugene Fletcher, and his store was ninety miles away, in Columbus.

Fletcher declined to speak with me for this project, so what I know about him is limited to what I could learn from various legal records. I know that he graduated from the Ohio State University’s School of Pharmacy in 1991, and that he was licensed by the Ohio Board of Pharmacy the following year. I know that for six years he worked as a pharmacist at retail drug chains and in a hospital-based pharmacy; in 1998, he purchased a pharmacy practice in a Columbus building that included a medical office and dental practice. The business was called East Main Street Pharmacy.

Given the distance between Volkman’s clinic and the pharmacy, some coordination was required between the two businesses. According to Volkman’s former security guard, a call was made from Volkman’s clinic “just about every day” to inform the pharmacist of the time when the doctor saw his last patient so that Fletcher knew when to expect his last customer. On some days, the pharmacist reportedly kept his shop open until midnight.

But such accommodations were apparently worth the trouble. Because in the weeks following his connection with Volkman, Fletcher saw a sharp influx of business and revenue. Records later discussed in DEA administrative proceedings show that his purchases of oxycodone and hydrocodone skyrocketed from 2004 to 2005 — specifically after September 2005, when his informal partnership with Volkman began. In 2004, East Main Street Pharmacy was the three hundredth largest purchaser of oxycodone in the state of Ohio. The following year, it jumped to the eleventh spot.

There were other noteworthy aspects of Fletcher’s new influx of customers. According to DEA documents, “nearly ninety-nine percent” of the people who filled Volkman’s prescriptions at his pharmacy didn’t live in Columbus, and more than 85 percent of those patients paid for their prescriptions in cash, which was more than seven times higher than the national average of cash-paying customers.

And around the time when Fletcher welcomed his new rush of business, an employee at Commerce National Bank noticed a spike in his deposits and placed him on a “watch list” for suspicious activity. Other records indicate that during the month his partnership with Volkman began, the pharmacist made cash deposits on consecutive days of $9,000; $9,000; $9,750; and $9,900. He would continue to make similar deposits over the following months. In October, Fletcher even called the bank to ask about the legally required threshold for filing a deposit disclosure form and whether he could avoid that by making deposits into two separate accounts.

Later, when DEA investigators asked about the due diligence he had performed to ensure that the doctor sending him so many customers was legitimate, Fletcher said that he had called Volkman, who told him about the MRI paperwork his patients produced in order to be seen and the blood tests the doctor ordered to ensure patient compliance. However, Fletcher admitted that Volkman’s patients sometimes asked him to sell them extra pills (requests he said he declined); he was also aware that other pharmacies closer to Portsmouth had refused to fill Volkman’s scripts. Fletcher apparently declined to call any of those pharmacists to hear their reasons because, as he told investigators, “I don’t communicate with other pharmacists.”

A former Volkman patient would later tell authorities that, during one trip to fill the doctor’s prescription at East Main, she was so high that her speech was slurred, her walk was unsteady, her head was hanging down, and she was “probably drooling.” And yet, when Fletcher was asked by investigators whether he believed that Volkman’s patients were addicted, he responded that it was “hard to say.” In those interviews with DEA agents, he maintained that decisions about the types and amounts of medications to prescribe belonged to a doctor, and that it was “not his job to question a physician.”

Volkman, it seems, had found a perfect partner: one who filled his prescriptions, didn’t ask too many questions, and even kept his shop open to accommodate the unusual travel time between physician and pharmacist. Among the records from Center Street submitted in Volkman’s trial was a printed page of directions from Mapquest.com. According to those directions, the estimated drive time between Center Street and Fletcher’s pharmacy was an hour and fifty-seven minutes.

#

Back on Center Street, Portsmouth police monitored Volkman’s operation closely. According to a search warrant produced by the department, within days of the clinic opening, local officers sent in a patient wearing a wire who waited five hours before being called to see the doctor. During that visit, Volkman asked about previous injuries and surgeries, as well as the medications the patient had previously been prescribed. His physical exam consisted of checking the patient’s reflexes and asking them to bend down to touch their toes. This visit resulted in the doctor writing prescriptions for 180 fifteen-milligram oxycodone pills, 180 ten-milligram Lorcets, 120 Soma 350-milligrams, and 90 two-milligram Xanax tablets. The patient was given a note with the name, address, and phone number of East Main Street Pharmacy, in Columbus.

Two days later, Portsmouth police sent in a second patient cooperating with their investigation. This time, documents indicated that there was a shorter wait, no physical exam, and Volkman wrote prescriptions for 270 oxycodone 30-milligram pills, 270 Percocet 5-milligrams, 120 Soma 350-milligrams, and 60 Xanax 2-milligram pills. According to police notes, Volkman instructed the patient to come back four days later, when he would give her more prescriptions.

And it wasn’t just police who were following events on Center Street. In the weeks after their falling-out, Denise Huffman expressed her shock and outrage in comments on a local online chat board. Whether Huffman’s outrage was genuine or feigned to make herself look innocent by comparison is unclear. But in one comment, she called Volkman “Dr. Doom,” and, in another, she wrote, “Seriously I can’t believe what I’m seeing…How can someone act one way and turn out to be this bad?”

In another comment, she asked what was taking the DEA so long to shut him down. “Wonder what they are waiting on,” she wrote. “Corpses on his front porch?”

#

At Volkman’s trial, numerous witnesses would help to paint a picture of what took place inside the Center Street house. But the testimony of two witnesses, a former patient and his mother, stood out.

Danny Colley was in recovery from a drug addiction, but had recently relapsed at the time that Volkman’s Center Street clinic opened. And on the witness stand, he described the toll that drugs had taken on his life. Pills had taken “everything imaginable” from him, he said: his kids, his relationship with his mother, his ability to work. On drugs, he said he had become a “complete monster” who didn’t care about himself or anyone else.

When the prosecutor asked him why he had gone to see Volkman at the house-turned-clinic, his answer was blunt: “’Cause that’s where the medication was.”

He went on to explain that he had heard about Volkman through the network of people who sold and used drugs. He did not have an appointment to see the doctor; he just showed up. He didn’t have any medical records with him that day.

During his testimony, when he was asked to describe what he looked like at the time, he said that he was “dirty” and “sweaty.” He said that he was frequently dope-sick at the time and, as a result, he could barely talk. “I was a drug addict,” he said.

Nevertheless, he was given an appointment to see the doctor. And Colley testified that, during the visit, he told the doctor that he had previously undergone spinal surgery, which was true, and he also told the doctor that he was a previous patient, which was not true. He testified that Volkman instructed him to bend over, and perhaps the doctor ran a hand up Colley’s back. “He just acted like he knew me, so I went along with it,” Colley testified.

Colley walked out that day with prescriptions for oxycodone, hydrocodone, Xanax, and Soma.

#

When Danny’s mother, Diana, found out that her son was going to a local pain clinic, she was extremely worried. Danny had recently gotten clean, and was living in transitional housing at the time. And it was painfully clear to her that he had relapsed. He couldn’t focus. He would nod off mid-conversation.

Diana Colley is not someone you want to tick off.

She’s tall and solidly built. By her own description, she was “raised up really hard” in a particularly gritty part of Portsmouth. She had previously worked as an assistant manager at a Walmart for a decade. And in the fall of 2005, she owned and operated a bar in downtown Portsmouth, and was also working as a prison guard at the state penitentiary in Lucasville, fifteen miles north.

Eventually, she found out where her son was getting his drugs. And as she described from the witness stand at Volkman’s trial, one day she decided to pay the doctor on Center Street a visit.

The house was crowded when she got there, with around twenty people sitting or standing on the front porch. Once she walked inside, she saw more people sitting on folding chairs in the living-room-turned-waiting-room. There was a woman who appeared to be some kind of nurse or receptionist, and when Diana asked to speak with the doctor, the woman responded that the doctor was currently with a patient. Soon thereafter, Diana grabbed the woman by the throat and, as she described from the witness stand, “kind of convinced her” to tell her where the doctor was.

The woman pointed toward Volkman’s exam room.

Diana proceeded to the room and opened the door into what appeared to be a converted bedroom. Volkman was sitting at a desk and talking to a patient.

Interrupting the conversation, Diana told the doctor her son’s name, and explained that he was an addict who had recently gotten clean. He was now strung out again and she pleaded with him not to write him any more prescriptions.

His response, as she would later recall, was strikingly calm. “I’ll take it under consideration,” he told her.

Diana wasn’t satisfied with the answer.

She swept the papers off his desk for emphasis and told the doctor that she had a .38 pistol in her car. “If you write another prescription in my son’s name, I will blow your brains out,” she told him.

#

Diana Colley’s fears were not unreasonable.

By this point, since Volkman’s arrival in southern Ohio, investigators had identified, or would soon identify, at least eight patients who had died within days of visiting him and filling his prescriptions. Many of those patients were under the age of forty. And the pattern continued on Center Street.

First was the death of Scottie Lin James, who died on September 29 after seeing the doctor at the house. And on the day after James’s death, a patient named Bryan Brigner made a visit to Volkman’s clinic.

Brigner was a thirty-nine-year-old father of four. He was a tall, lanky guy who kept his hair long, wore a Dale Earnhardt baseball hat, and always kept a pack of Marlboros in the breast pocket of his T-shirt. His daughter told me, “He just loved his kids more than anything.”

A carpenter by trade, Brigner had worked in various demanding physical jobs, including construction, logging, and shifts at a local cabinet factory. But he had been collecting disability for six years, due to a series of injuries and ailments. In 1995, he was in a car wreck where he broke his nose and injured his back. In 2001, he was in another car accident where he injured his back and sustained nerve damage. His medical records also mentioned a number of additional on-the-job injuries, and a series of MRI tests and X-rays he had undergone in an effort to pinpoint the exact source of his pain.

Brigner had seen Volkman twice on Findlay Street before the doctor left Tri-State, and during those visits, he had complained of pain in his neck, side, and lower back. In response, he had received prescriptions for Lortab, Valium, oxycodone, and Soma. His third visit to the doctor was on Center Street. That day he received prescriptions for two opioids (oxycodone, hydrocodone), a muscle relaxer (Soma), and a sedative (Valium). His daily medication regimen, as laid out in Volkman’s notes, recommended that he take eight 30-milligram oxycodone pills over the course of the day, in addition to eight Lortabs, three 10-milligram Valiums, and three Somas.

Less than forty-eight hours after his last visit to the doctor, Brigner died at home in his apartment in West Portsmouth. After both an autopsy and toxicological analysis were performed, his death certificate recorded his cause of death as “Cardiopulmonary Arrest” due to “Drug Intoxication.”

#

On October 4, 2005, a local judge signed a seventy-page search warrant for the house on Center Street. The document, prepared by Portsmouth police, noted that Volkman was seeing between thirty and fifty patients a day at the house, often until late in the evening. It also stated that no pharmacies in Scioto County would fill Volkman’s prescriptions. Officers wrote, “Many patients appear to be very young, possibly late teens, early twenties…[a]nd display no signs of injuries or malformations.” Elsewhere, the warrant noted: “Toddlers have been observed in office in presence of above-described patients and can be heard on a recording made by a confidential informant who was seen as a patient.”

On that day, WSAZ Channel 3 reporter Randy Yohe was at the TV station’s office in Huntington, West Virginia, when he got a call from a law enforcement source about the impending raid of the house on Center Street. Knowing this would be a worthwhile story, he hustled into a car, hopped on Route 52, and headed west toward Portsmouth, about an hour away. When he arrived on Center Street, he found that the house had been cordoned off with yellow crime-scene tape. Portsmouth police officers had backed a truck up to the house and were wheeling away boxes from inside. Yohe saw patients being handcuffed and questioned. The police chief and the assistant county prosecutor were both on the scene.

Police made a thorough inventory of what they found in the house that day. They collected medical files from the top of the desk and the floor in Volkman’s makeshift office. They took his briefcase from the trunk of his black Subaru sedan. They combed through filing cabinets in the kitchen that were stocked with more than four hundred patient files. They counted the cash they found in a Sentry safe in a kitchen drawer; it amounted to $3,212.14. They wrote in one note that they had found “1 Blue pill labeled 4356, 20 MG found in hallway between [living room] and kitchen.”

Outside the house, one officer tallied the out-of-county cars that were parked on the block at the time of the raid. There were thirteen from Kentucky, four from Ohio, and one from West Virginia. “Most traffic bypassed the street due to the police vehicles in the street, and still the traffic was heavier than normal for a residential street,” the officer wrote.

On the day after the raid, a story ran in the Portsmouth Daily Times with the headline: “Dr. Volkman Again Target of Police Raid.” In the article, one Center Street resident described recently seeing license plates from Indiana and Michigan among the cars on the street. “It was just a racket down there. I didn’t know what was going on, but I’m glad it’s taken care of,” he said. The article estimated that fifty people were inside the house when police arrived.

Portsmouth police chief Charles Horner told the Times that it was “very strange and highly unusual for law enforcement to come across something like this.”

Assistant Scioto County prosecutor Pat Apel, who was also interviewed, confirmed that his office was investigating Volkman. But he spoke about the challenge of bringing a successful criminal case against a doctor. “To prosecute a case that involves a physician and prescribing drugs you have to show it was not a bona fide treatment of a patient,” he said. “That has to do with what the subjective intent of the doctor is…That’s pretty difficult.”

Accompanying the article was a picture taken from the backyard of 1310 Center during the raid. Six people were pictured, sitting on folding metal chairs, looking dejected. They appeared to be in their thirties, forties, and fifties. A few were smoking cigarettes. A uniformed police officer stood behind them, his hands clasped behind his back, his eyes obscured by dark sunglasses.

Volkman was not arrested that day, although he was temporarily handcuffed. As part of the raid, he received a legal notice that the house could no longer be used as a clinic. But for the time being, he was not charged with any crime.

And even after two raids of his offices by law enforcement, he was determined to continue working. According to his own remarks about this time, when the Center Street raid occurred he had already signed a multi-year lease and placed a $10,000 down payment on an office in downtown Portsmouth. But that plan was no good now. He needed to leave town.

He had a new clinic up and running within days.

Prescription for Pain: How a Once-Promising Doctor Became the "Pill Mill Killer" is available for pre-order now.

Here's a short piece from A Creature Wanting Form about pain.

Waltham, Massachusetts

Someone was frying meat in the kitchen attached to the waiting room and so it smelled like fried meat. I paged through an old issue of an old beauty magazine that was old enough that the people inside maybe weren’t even beautiful anymore at this point and I sat there silently with six of you suffering in your own way and waiting to take your chances with a stint in the needling device.

I put down the magazine and scrolled through my phone and read a story about how the government is using dental exams to ascertain the real age of immigrants they apprehend at the border.

Someone in the professor’s chamber was sobbing in a strange tempo. Their skin being punctured with the weight of a pianist’s finger stabs.

One boy from Bangladesh said he was fourteen when they caught him with the drones and everything but they didn’t believe him so they sent him for what he thought was a routine dental exam but instead what they did was check his teeth like you would if you were sizing up a race horse or like when you cut down a tree and open it up and dig around inside its tree meat to find out how many rings it has.

There are only two things most of us know for sure if we are lucky which are our birthdays and our names but we’ve long taken even those away from people who we decide don’t deserve them. Even now we promote children into adults through the power

of bureaucratic transubstantiation and that is because you can treat them worse after that. You just magically rob them of a few years of assumed innocence and then it’s basically like whatever.

I didn’t want it to but the frying meat was starting to make me hungry and then a crying woman was carried up the stairs into the room by her sons and it looked like her leg was in real bad shape sort of sideways and we all shut the fuck up as she tried to settle in and find a place to situate herself in the pain waiting room on the bad pain waiting room chairs and I thought it’s strange how the presence of someone else in serious distress can make an already silent room more silent still as if coughing or even breathing out loud would be impolite to the person in question but also the concept of pain itself.

When real pain enters the room you have to respect it and hope you don’t catch its eye like it’s a bear you spot just off in the distance in the woods. So you don’t make too much noise or any sudden movements and you back away very slowly.

Later you think you really pulled something off there and you tell the story about how you outsmarted a bear to your friends but you didn’t it just wasn’t interested in you at that particular juncture and will be circling back around shortly.

All of that talk about pain clinics also reminded me of this chapter from the Welcome to Hell World book which goes in part like this:

I went back to the Pain Center yesterday the one I mentioned previously and I filled out the forms they make you fill out every time on that clipboard there Welcome to Pain Management it says which would’ve been another good name for this book.

It’s essentially page after page of a questionnaire asking you about whether or not you’ve ever gotten into trouble for having drugs or if you’ve ever misused your drugs or had encounters with the law due to drugs or if people have ever told you you have an issue with drugs and for most of the answers I answer no because it’s the truth and mostly what they’re interested in are opioids anyway but the real thing they’re trying to figure out here is whether or not you have your pain coming. They are gonna treat you either way but if you’ve already used up your physician empathy points and went and fucked around with medications then they’re not going to treat you as well or as effectively as they might have otherwise. When they see you’ve been addicted to things in the past the doctors just like the cops and the TV news and the readers and the viewers who delight in distancing ourselves from other people who are more deserving of pain than we are think that it’s a just penance.

Another thing they have you do is try to describe not just your degree of pain but also the specific qualities of pain. They ask like is it burning stabbing piercing throbbing dull aching and I don’t know how to answer those things because I never graduated from the Pain Sommelier Academy. I am not equipped with the vocabulary to tease out the subtle notes of pain inside of my own body and I don’t think we’ve all really gotten together and come to a consensus on what the specific difference between any of those terms are have we or did I just miss it? We’re speaking in a language that we don’t understand and that no one else understands and the person who’s trying to interpret it the doctor might as well be imagining a monkey playing the cymbals in his brain while you’re talking which is what they do because your doctor never listens to you anyway.

One thing the doctor said they could do to figure out what’s going on with me is poke needles into the nerves in my back and the front side of my body at the same time and try to see which ones light up or something when they sent a little charge through my body. I think. It’s a very painful procedure he said but I didn’t really listen to what else it entailed because you never listen to your doctor anyway.

Every time I talk to a doctor it’s like I just walked into a room and met nineteen different people at a cocktail reception or something and you know there is no way you are going to remember all of their names or where they’re from or what they do but the people are actually things that are wrong with you. So you try your best to pick out one of them that will stick.

Experiencing pain sometimes is like suspecting there’s a dead mouse in your walls like you can vaguely smell it so you go poking your snout around by the sink and under the stove or wherever and you know you know you know it’s there somewhere but you can’t find it or tell anyone else where to go to pull it out. You know it’s in the kitchen say but that’s as close as you can get to narrowing things down and then you just have to wait for decomposition to take over eventually and in the long run none of it will be there and it will have never been there.

And of the chapter We have to hammer on the abusers in every way possible – also from the WTHW book – which goes in part like this:

How much money would you need to go and kill someone? You wouldn’t even have to be there for it or pull a trigger or do anything else to get your hands dirty you would just collect the money and somewhere out there someone you have never met would die. Not just die though they’d die most likely after a period of terrific pain and addiction and withdrawal and perhaps spend months or years before their death resorting to all manner of desperate measures to acquire the one thing in life that brings them relief. Maybe they’d hurt some people along the way too. What can I put you down for that? What’s it gonna take for me to see you walking out of here today the proud owner of a body?

Between 2008 and 2016 the Sacklers, the billionaire family behind Purdue Pharma, extracted $4 billion in profits from the company in large part due to sales of OxyContin the highly addictive pain medication they buried the country under. During that time around 235,000 people died from overdoses from the drug so if we do a little back of the napkin math here that breaks down to about $18,000 a head. Would that do the trick for you? Or maybe you’d need to move a little weight to make it worth the heavy conscience. I’m not saying you would be comfortable killing 250,000 people that would be crazy. What about twenty people to the tune of about $360,000? You could get a pretty decent house in most markets for that kind of money. Not in Boston of course but somewhere they have to still have houses for that little.

The rot at the heart of America’s worst family has been known for some time now but newly un-redacted documents in the state of Massachusetts’ lawsuit against the family show their direct involvement in a push to aggressively increase sales of the drug and downplay the risks of addiction.

In 1996 the Sacklers and Purdue had a launch party for OxyContin which is a pretty funny thing to have a party for in retrospect. It would be like having a launch party for a new type of cancer. There would be passed hors d’oeuvres and even though it’s an open bar the line would be kind of long and someone would be like this fucking line at the bar is too long at the cancer launch party let’s get out of here.

But around the debut of the Oxy thing one thing Dr. Richard Sackler said at the time was this which was that it would be “followed by a blizzard of prescriptions that will bury the competition.” And he’s right there if by competition he means sick patients a lot of them were certainly buried.

Not his problem though because years later after the harmful effects of the drug started to become more widely discussed Sackler devised a way to shift the blame.

“We have to hammer on the abusers in every way possible,” he wrote in an email in 2001. “They are the culprits and the problem. They are reckless criminals.”

Imagine if there was a family and a company that patented and marketed the massively popular concept of dying in a fiery car accident. We’d probably go ahead and stop them right. You would hope we would stop that. We wouldn’t because I just remembered the concept of the gun lobby but still you would hope that we would.

Around 2009 the Sackler family contracted the services of McKinsey the consulting firm of choice for rich sociopaths around the world. Among the ideas they came up with according to documents filed in the lawsuit was a slide presentation that said prescriptions could be increased by getting doctors to think opioids would offer “freedom” and “peace of mind” and give people suffering “the best pos- sible chance to live a full and active life.”

As ProPublica reported, “In a meeting with Purdue executives, McKinsey planned how to ‘counter the emotional messages from mothers with teenagers that overdosed in [sic] OxyContin’ by recruit- ing pain patients to talk about the need for the drugs.”

Another bit of advice the consultants had was to focus on the doctors who already seemed willing to prescribe the drug prolifically which is just sound economic theory in my opinion. Seeing that “prescription rates rose in tandem with visits from sales reps to doctors,” McKinsey “recommended increasing each salesperson’s quota from 1,400 visits a year to closer to 1,700.”

In 2009 one Purdue sales manager started to grow a conscience of sorts and wrote to a company official that they seemed to be pushing the drugs to a particularly unethical illegal pill mill.

“I feel very certain this is an organized drug ring,” they wrote in an email. “Shouldn’t the DEA be contacted about this?”

The DEA was not contacted about this.

None of which is to say the Sacklers are all bad. For example at one point they looked into developing medications that would help those addicted to their product. Dr. Kathe Sackler participated in talks about such a thing in 2014 with a team the court documents suggest.

“It is an attractive market,” they outlined in a presentation. “Large unmet need for vulnerable, underserved and stigmatized patient population suffering from substance abuse, dependence and addiction,” they said. Wouldn’t it be beneficial for the company to transition into an “end-to-end pain provider”?

They also considered dipping their toes into the booming Narcan market, the reverse-overdose agent, and due to they are marketing geniuses they thought the best way to do that would be to push Narcan on the same doctors who prescribed the most Oxy which would be like pushing diarrhea medicine to restaurants that sold the most tacos.

They didn’t end up going ahead with those plans in the end but good news though because Richard Sackler did receive approval on a patent for a medication meant to help people suffering opioid addiction recently.

Anyway it goes on like that for a while. You can read the rest in the book if you like.

That's all for today. Be back sooner than usual with the next issue over the weekend I think.

Bye!