Memory is, achingly, the only relation we can have with the dead

How do we get vengeance on ourselves?

“There’s a revolution coming and I’m happy to be paht of it,” Felipe said and normally I wouldn’t type out the Boston accent or any accent like that but there was something inspiring about hearing it said in the same voice I have. I got inspired for a minute is what I’m saying.

That feeling was also due to the large crowd of people who were listening to the representative of the Boston Independent Drivers Guild speak. He was there with a number of other labor groups protesting in solidarity at a walkout organized by workers at the Boston-based e-commerce giant Wayfair. Around two thousand of us had gathered on Wednesday afternoon in Copley Square at the foot of Trinity Church with the glaring sun bouncing off the Hancock Tower because we were fed up with companies in general and Wayfair in particular profiting off of the torture of migrants which is what is known as the baseline level of decency you can have at this point in our country-wide slide into the abyss.

Lasy week a group of workers at Wayfair a company with revenue of nearly seven billion in 2018 were made aware that they were selling beds to furnish a camp on the southern border. 547 of them signed a letter addressed to their bosses asking that they cease all business with such camps and the bosses said no and so now it was time to walk out.

“I am so proud to see so many people here. It’s workers, and workers’ struggles, and it’s capitalism that keeps the workers down,” Felipe went on. “I think this is one great step for Boston to see so many people out here today sticking up for their rights. As Uber drivers we’re trying to organize. Keep doing what you’re doing. Don’t stop. If you believe in it it will happen,” he said.

The megaphone passed back and forth between numerous other groups including Pride at Work the LGBT constituency of the AFL-CIO whose rep asked us to keep in mind how much of the immigration issue is driven by the wars of imperialism we’ve conducted in countries throughout the world and he is right about that.

One thing the worst people alive like to say is that we wouldn’t be holding people in camps if they didn’t come here in the first place we didn’t force them to come they like to say but considering our history of disruption and malfeasance around the world and in Central America in particular we sure did give them a pretty good reason to try to get the fuck out.

Tom Brown an employee at Wayfair took the mic next explaining that he was nervous as he wasn’t used to this sort of thing and there were so many cameras which was not an understatement there were a lot.

“We know what we believe in,” he said to applause. “We want to do what’s right. At Wayfair, we have a great team, and we talk internally about how we hire the best people. We’re looking for the best and the brightest, and those just so happen to be the people that care the most, people we know will fight for what’s right even if it’s a difficult conversation right now...”

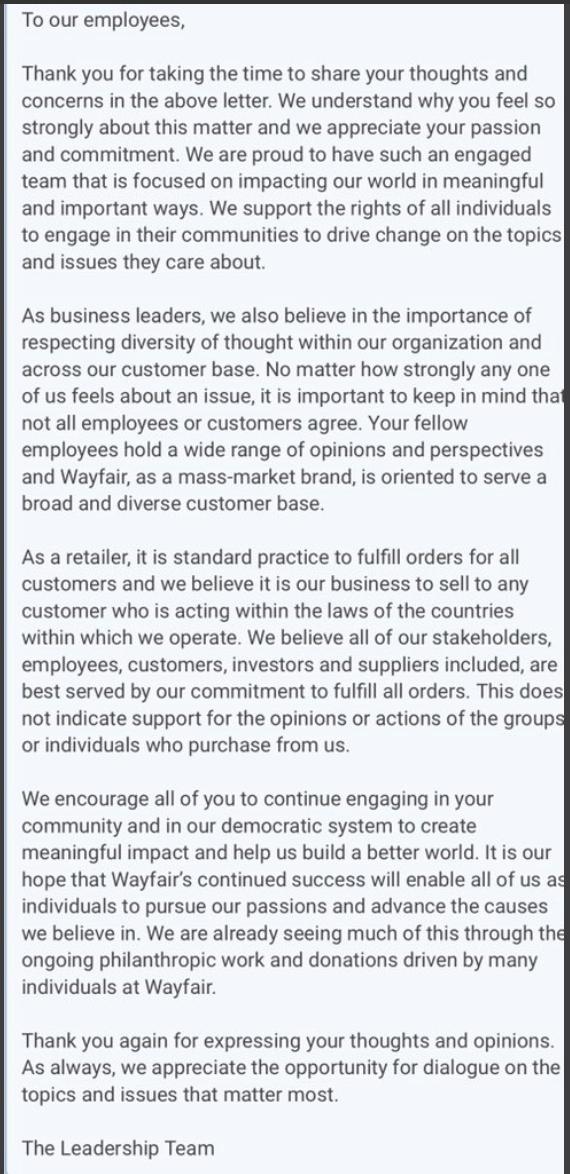

Here’s what the workers said management sent to them in response to their request to stop doing the baby jail stuff.

I’m jacking off the air so hard I’m going to lift off the ground like a helicopter.

After Brown was done with the crowd he spoke to a scrum of reporters motherfucker get your microphone out of my asshole camera people are the pushiest motherfuckers in the world.

“Last week we found out about the sale to the detention center and that we’re profiting off this, and we’re not comfortable with that,” Brown said. “We want to make sure what we’re doing is right. For me personally, I’m not a manager, but for me there’s more to life than profit, and when we see an injustice like this we’re going to do something about it. We sent that petition to management hoping that they would do the right thing.”

They didn’t of course although they still might but that remains to be seen. Wayfair did announce they were donating $100,000 to the Red Cross which is very nice but doesn’t really have much to do with being in bed or rather being in the bed business with the baby jails.

One thing Wayfair likes to say is that they “believe everyone deserves a place to call home.”

Then I stopped recording stuff because there were roughly five million reporters there so I figured what everyone else said was going to be adequately covered and then I walked around and saw a bunch of people and one person I saw told me his friend is a Delta flight attendant and the company had just done a whole pr thing about these fancy designer uniforms they had recently rolled out but the uniforms are so cheaply made the dye comes off on their skin and they’re all getting rashes and sick from them but Delta won’t do anything about it so that was great to hear.

I made what was both a very good decision and a huge mistake to read Susan Sontag this morning. It was the former because it helped me think through a question I have been wrestling with and the latter because as often happens when reading her it instilled in me a foul and abject melancholy and an understanding that I will never write something anything like that and in fact may not even be engaged in the same profession as she was.

Regarding the Pain of Others was Sontag’s final book in 2004 and among other things it contends with the inevitable distance between the viewers of images of the suffering in war and the subjects of those images who are doing the suffering.

It begins with a discussion of Virginia Woolf’s 1938 book Three Guineas. In it Woolf questions a correspondent: “How in your opinion are we to prevent war?”

Woolf suggests she and the man she is communicating with look at the same specific photos of violence during the fascist rise in Spain at the same time and register how their impressions of them might vary which they will inevitably because war is a man’s pursuit and she is a woman and not naturally inclined to war like we are which is fair.

“This morning's collection contains the photograph of what might be a man's body, or a woman's; it is so mutilated that it might, on the other hand, be the body of a pig. But those certainly are dead children, and that undoubtedly is the section of a house. A bomb has torn open the side; there is still a birdcage hanging in what was presumably the sitting room...”

I’m glossing over the overarching thrust of this part here because it would be impossible to summarize the entire book-length essay and to be honest I’m probably too fucking stupid to even understand it but I wanted to include that quote because it was so perfectly disgusting to me. It might be the body of a pig.

Sontag returns to that imagery later on as well:

“When Woolf notes that one of the photographs she has been sent shows a corpse of a man or woman so mangled that it could as well be that of a dead pig, her point is that the scale of war's murderousness destroys what identifies people as individuals, even as human beings. This, of course, is how war looks when it is seen from afar, as an image.”

“Victims, grieving relatives, consumers of news all have their own nearness to or distance from war,” she goes on.

“The frankest representations of war, and of disaster-injured bodies are of those who seem most foreign, therefore least likely to be known.”

And when it comes to photographs taken closer to home of our “own people” suffering a certain level of discretion is enforced whether through unspoken cultural norms or literal dictate by the institutions of government or corporate media who levy the judgments about whose pain can be depicted.

How often for example have you seen the image of a bullet-strewn body in newspapers or on cable news following one of our near weekly mass shootings? What does a schoolchild with a bullet in her head look like? I don’t know do you? Not a white American child in any case I am sure I have seen dead children from elsewhere around the world but that is elsewhere and so there is an additional level of distance both the one installed by the photograph itself and also the chasm of geography and culture that desensitizes my reaction.

How often do you see the coffins of American soldiers coming home from being killed never mind their actual bodies? It wasn’t until 2009 that an eighteen year ban on photographing military coffins was lifted do you remember that? Remember how we were literally not allowed to see the coffins what the fuck.

“The military said the ban protected the privacy and dignity of families of the dead. But others, including some of the families as well as opponents of the Iraq war, said it sanitized the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and was intended to control public anger over the conflicts,” the New York Times reported at the time.

There’s a reason for that of course which is obvious but let’s hear it anyway.

“During the Vietnam era, war photography became, normatively, a criticism of war,’ Sontag writes and the emphasis here is mine": “This was bound to have consequences: mainstream media are not in the business of making people feel queasy about the struggles for which they are being mobilized, much less of disseminating propaganda against waging war.”

“So many Americans want to have Memorial Day once a year, when they go to the beach and cook hot dogs in the backyard,” Jon Soltz the chairman of VoteVets.org said at the time of the coffin photograph ban reversal.

“This is a way for Americans to see and honor the sacrifice of our fallen when it occurs. It's something our public should be aware of.”

Yes but what does looking at a coffin covered in a flag even make you feel? It’s different than if it were the body that may be a pig for all we know isn’t it?

I happen to agree with Soltz’ way of thinking in any case and I also happen to think we should have bodies on the front page every day whether they are own homegrown bodies destroyed by our slavish devotion to gun culture or bodies we create abroad through our pointless wars of empire or as the case is this week bodies along the border that we create through our evil xenophobic and racist immigration policies.

Did you see the photo? The one of the dead father carrying his dead little baby daughter in his arms across the Rio Grande face down and drowned after having fled violence in El Salvador hoping to find safety and peace in the United States?

There was of course almost immediately a debate about the ethics of publishing such a photo because that is something that is easier for us in the media to think about. There are rules and standards we can apply to our profession and it grounds us in reality to think about them it innoculates us from the real horror at hand which is unimaginable and for which there is seemingly no overarching order or standards whatsoever. It’s more comfortable to argue balls and strikes is what I’m saying.

I am trying to be sympathetic to some of the arguments against publishing the photo to be clear particularly ones that take into account the use of marginalized and people of colors’ bodies for sensational exploitation. But I can only be persuaded so far when it comes to that. I think we need to see what we’re doing as a country and in our name. I don’t think people should be allowed to look away.

A father and his daughter drowned.

What does that sentence do for you? Not much right? Ah that’s too bad you say but when you see her little red shorts and his t-shirt pulled up and both their faces submerged in the murky water that does something different.

Here’s what the editorial board of USA Today wrote today in explaining their decision to publish the photo as one example and I think it’s fine reasoning:

This is a story that must be told – fully and truthfully, with context and perspectives from all sides, as the nation and its political leaders here, as well as in Mexico and across Central America, grapple with the complex issues surrounding legal immigration. Death is a constant along the border, but rarely is it captured in such a direct way. And photography has the power to freeze a moment in time, one that in this case encapsulates the danger and desperation surrounding the exodus of immigrants primarily from Central American countries.

“In the era of tele-controlled warfare against innumerable enemies of American power, policies about what is to be seen and not seen by the public are still being worked out,” Sontag wrote.

Throughout the book she is usually talking specifically about images from armed conflict and war as we think of it when we think about war but that seems a broad enough framework for me to include what is happening along our border. It is not warfare per se in that we are not as of yet shooting our weapons at the migrants. We are aiming them at them to be clear but the literal trigger has not yet been pulled just a series of other more detached mechanisms that lead to more indirect deaths which are much more palatable for polite society. A policy-born murder is easier for Americans to swallow than a well no I don’t even believe what I was about to write we are actually fine with direct murders too now that I think about it never mind.

“Television news producers and newspaper and magazine photo editors make decisions every day which firm up the wavering consensus about the boundaries of public knowledge. Often their decisions are cast as judgments about ‘good taste’—always a repressive standard when invoked by institutions. Staying within the bounds of good taste was the primary reason given for not showing any of the horrific pictures of the dead taken at the site of the World Trade Center in the immediate aftermath of the attack on September 11, 2001,” Sontag writes and as I’m writing this there’s a headline on CNN that says HEARTBREAKING: IMAGE OF DROWNED FATHER & TODDLER SHOWS MIGRANTS PERIL and they showed the bodies briefly and then went to a panel discussing it. On MSNBC they’re talking about Mueller testifying and on Fox News they have a live feed of a Trump speech in which he is saying he is the best at Bible.

“And television news, with its much larger audience and therefore greater responsiveness to pressures from advertisers, operates under even stricter, for the most part self-policed constraints on what is ‘proper’ to air. This novel insistence on good taste in a culture saturated with commercial incentives to lower standards of taste may be puzzling. But it makes sense if understood as obscuring a host of concerns and anxieties about public order and public morale that cannot be named, as well as pointing to the inability otherwise to formulate or defend traditional conventions of how to mourn. What can be shown, what should not be shown—few issues arouse more public clamor.”

Another argument often used against showing pictures of suffering and death is couched as concern for the families Sontag says referencing the video of the execution of Daniel Pearl by Al-Qaeda in Pakistan in 2002 after which a similar debate about the ethics of sharing such a vivid horror erupted.

“With our dead, there has always been a powerful interdiction against showing the naked face,” she writes and that has been true from the Civil war through World War II and onto the present. “This is a dignity not thought necessary to accord to others.”

“The more remote or exotic the place, the more likely we are to have full frontal views of the dead and dying,” from postcolonial Africa to the Rwanda Tutsis and violence in Sierra Leone.

“These sights carry a double message. They show a suffering that is outrageous, unjust, and should be repaired. They confirm that this is the sort of thing which happens in that place. The ubiquity of those photographs, and those horrors, cannot help but nourish belief in the inevitability of tragedy in the benighted or backward—that is, poor—parts of the world.”

And then we come to think of those places as being the places where suffering just happens and it’s easier for us to not think about it when we cause the suffering for example we can just not think about anything going on in Central America and who gives a fuck until the people their come looking to us for help?

This journalistic custom inherits the centuries-old practice of exhibiting exotic— that is, colonized—human beings: Africans and denizens of remote Asian countries were displayed like zoo animals in ethnological exhibitions mounted in London, Paris, and other European capitals from the sixteenth until the early twentieth century. In The Tempest, Trinculo's first thought upon coming across Caliban is that he could be put on exhibit in England: ‘not a holiday fool there but would give a piece of silver… When they will not give a doit to relieve a lame beggar, they will lay out ten to see a dead Indian.’

The exhibition in photographs of cruelties inflicted on those with darker complexions in exotic countries continues this offering, oblivious to the considerations that deter such displays of our own victims of violence; for the other, even when not an enemy, is regarded only as someone to be seen, not someone (like us) who also sees.

So like I said I understand and I want to appreciate the argument like the one put forth today by the National Association of Hispanic Journalists:

But I don’t know. I also one want appreciate arguments like this one put forth by a reporter who had found himself working with photographer Nick Ut the man who took the famous picture of the naked girl running from napalm. Read this thread here it’s quite good:

So should we show photos like these or not?

I don’t know. I think so.

I’m going to quote even more at length from Sontag’s piece here for a bit because it’s worth reading in full.

To designate a hell is not, of course, to tell us anything about how to extract people from that hell, how to moderate hell's flames. Still, it seems a good in itself to acknowledge, to have enlarged, one's sense of how much suffering caused by human wickedness there is in the world we share with others. Someone who is perennially surprised that depravity exists, who continues to feel disillusioned (even incredulous) when confronted with evidence of what humans are capable of inflicting in the way of gruesome, hands-on cruelties upon other humans, has not reached moral or psychological adulthood.

No one after a certain age has the right to this kind of innocence, of superficiality, to this degree of ignorance, or amnesia.

There now exists a vast repository of images that make it harder to maintain this kind of moral defectiveness. Let the atrocious images haunt us. Even if they are only tokens, and cannot possibly encompass most of the reality to which they refer, they still perform a vital function. The images say: This is what human beings are capable of doing—may volunteer to do, enthusiastically, self-righteously. Don't forget.

And here I think she gets at the key question what we’re supposed to think when we see the bodies in the river or wherever they end up.

“Who caused what the picture shows? Who is responsible? Is it excusable? Was it inevitable? Is there some state of affairs which we have accepted up to now that ought to be challenged?

All this, she writes, “with the understanding that moral indignation, like compassion, cannot dictate a course of action.”

More.

IMAGES HAVE BEEN reproached for being a way of watching suffering at a distance, as if there were some other way of watching. But watching up close—without the mediation of an image—is still just watching. Some of the reproaches made against images of atrocity are not different from characterizations of sight itself. Sight is effortless; sight requires spatial distance; sight can be turned off (we have lids on our eyes, we do not have doors on our ears). The very qualities that made the ancient Greek philosophers consider sight the most excellent, die noblest of the senses are now associated with a deficit.

It is felt that there is something morally wrong with the abstract of reality offered by photography; that one has no right to experience the suffering of others at a distance, denuded of its raw power; that we pay too high a human (or moral) price for those hitherto admired qualities of vision—the standing back from the aggressiveness of the world which frees us for observation and for elective attention. But this is only to describe the function of the mind itself.

There's nothing wrong with standing back and thinking. To paraphrase several sages: "Nobody can think and hit someone at the same time."

There is a possible inverse of focusing too much on the destruction and suffering of war too she writes and that is the potential the images have not to chasten us out of violence altogether but rather to inspire us to commit more of it as an act of revenge or justice.

If the photographs Woolf was contemplating “could only stimulate the repudiation of war” to one person to another person “surely they could foster greater militancy on behalf of the Republic.”

“To an Israeli Jew, a photograph of a child torn apart in the attack on the Sbarro pizzeria in downtown Jerusalem is first of all a photograph of a Jewish child killed by a Palestinian suicide bomber. To a Palestinian, a photograph of a child torn apart by a tank round in Gaza is first of all a photograph of a Palestinian child killed by Israeli ordnance.”

Sometimes you can even use images of violence like say for example the 9/11 destruction to justify and sell a war in a country that had nothing to do with any of it whatsoever.

The horror of any given image in other words is always going to be reflected by which vantage point you are looking at it from.

Worth asking again:

Who caused what the picture shows? Who is responsible? Is it excusable? Was it inevitable?

Here’s where things get difficult when it comes to the case of the dead and suffering migrants along our border though which is that it isn’t any enemy who is responsible for the violence we are gazing upon it is us. We did it. How do we get vengeance on ourselves? Who do we attack?