Maybe even approach a level of serenity

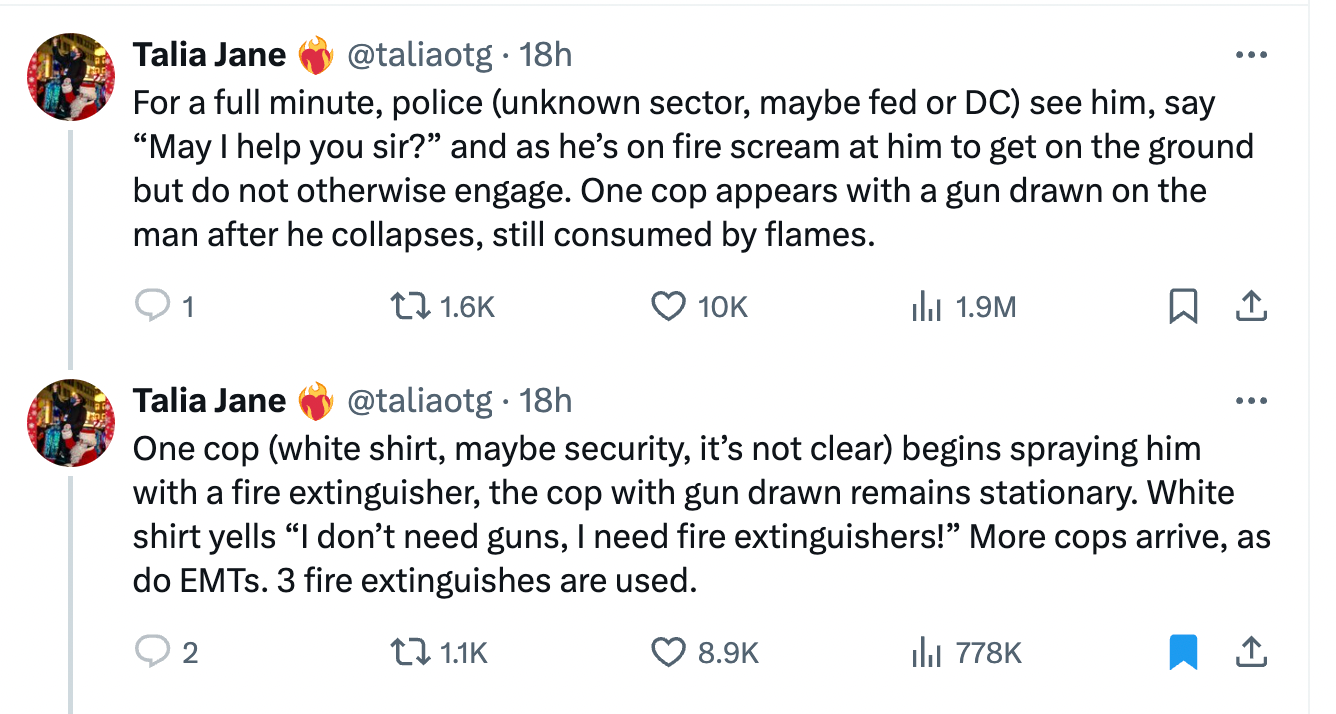

I am sort of struggling to find the words to write about this – and please skip over this part if you are sensitive to talk of self harm and suicide – but a twenty five year old active duty member of the U.S. Air Force named Aaron Bushnell self-immolated outside of the Israeli embassy in Washington D.C. yesterday. He has since reportedly succumbed to his injuries. In a video he was streaming of his act of protest reported on by Talia Jane on Twitter (and not watched by me) Bushnell said that he would "no longer be complicit in genocide." After lighting himself on fire he yelled “Free Palestine.”

There's a lot to process here but I can't help but focus on the detail of a cop of some kind holding his gun on a man as he's burning to death on the ground. You could do a lot worse in terms of nation-defining metaphors.

This too:

"I don't need guns, I need fire extinguishers!"

“I will no longer be complicit in genocide. I’m about to engage in an extreme act of protest,” Bushnell said on the stream as he approached the embassy. “But compared to what people have been experiencing in Palestine at the hands of their colonizers, it’s not extreme at all. This is what our ruling class has decided will be normal.”

Meanwhile in Gaza:

You might read this New Yorker piece from 2012 on the history of self-immolation as a form of protest.

Contrary to common belief, the practice does not originate in the Vietnam era and is not confined to Asia (where, thanks to Hinduism, Buddhism, and other religions, posthumous cremation is far more common than in the West). Rather, it is a millennia-old practice in both the West and the East, where it has long commanded mass sympathy and outrage unmatched by other forms of suicide. The sociologist Emile Durkheim separated suicides into four types: the egoistic, the altruistic, the anomic (moral confusion), and the fatalistic. Perhaps self-immolation captivates so thoroughly because it wins on all counts. It is the ultimate act of both despair and defiance, a symbol at once of resignation and heroic self-sacrifice.

...

Why? What motivated them? I put the question to any number of historians of self-immolation, but the best answer came from a scholar based in Washington, D.C., Timothy Dickinson. “Fire is the most dreaded of all forms of death,” he said, so “the sight of someone setting themselves on fire is simultaneously an assertion of intolerability and, frankly, of moral superiority. You say ‘I would never have the guts to do that. It’s not that he’s trying to tell me something, but that he’s commanding me.’ This isn’t insanity. It’s a terrible act of reason.”

Rest in peace Aaron. I wish that you had not done that. Had been made to feel that you had to do that. That only something so drastic was necessary to get the powerful to take notice. I hope that they do.

Sorry for the abrupt shift here but today's main thing is a talk with author John Oakes about his new book The Fast: The History, Science, Philosophy, and Promise of Doing Without. Although now that I think of it much of the book and our talk focuses on hunger strikes which are another political act of protest aimed at trying to force those in power to pay attention.

Oakes writes:

When implemented as a hunger strike, fasting signals purity of purpose. It signifies that the faster is sincere and allied with a higher moral power (or believes she is). In the fall of 2021, the young climate activists of the Sunrise Movement reaffirmed fasting’s relevance when they engaged in hunger strikes in front of the White House. In the same period, New York City cabdrivers called for a mass hunger strike to call attention to their crippling debt. “It’s dangerous and it’s drastic,” Bhairavi Desai, executive director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, said at the time. “And I tell you, we’ve been pushed to that edge.” The taxi drivers fasted for fifteen days before winning their case, causing city officials to renegotiate the amount due to lenders. The Sunrise strikers didn’t immediately win their cause—the environmental initiatives they were battling for didn’t clear Congress at that time, although they were resurrected months later—but they demonstrated the intensity and clarity of their purpose to a broad public and, of course, received plenty of media coverage as a result. “As a person I’m really small, and before, that might have made me feel ineffective,” said Kidus Girma, one of the hunger strikers. “But now I see that a lot of small people add up to something big, and I feel big in my smallness.” Fasting is a demand to be seen and to be heard. It provides a clear answer to the question: “How dedicated are you to your cause?”

“I’m always aware of being a flea near these giants and of my perceived inability to put convincing arguments on the table,” said Stella Jean, a prominent Haitian-Italian designer who undertook a hunger strike in protest at the racism of the fashion industry in February 2023. “I had nothing else left to barter with.” At its most basic, a fast is a refusal to plug one’s mouth with food. But that act can also be a call of sorts. In ancient Ireland, people were “fasted against” or “fasted upon,” as they still are to this day in India. In these cases, fasting becomes a means to leverage power. It opens a portal to a spiritual realm, whose powers can be summoned to aid the faster and to right wrongs... Throughout recorded history, the weapon of fasting has been adapted according to social need. From premedieval times, it has often signaled a ritual challenge, a drive for independence, becoming a threat to officialdom.

The book is a thorough history of fasting throughout world history with appearances from a wealth of notable fasters including Achilles, Augustine of Hippo, Buddha, Hippocrates, Thomas Jefferson, Cesar Chavez, St. Patrick, Bobby Sands, Franz Kafka, Abraham Lincoln, Leon Trotsky, Mark Twain and many others.

Before we get to our talk I wanted to re-share this piece real quick since it's been two years now since we lost Mark Lanegan.

I’m looking at him on stage right now. He sounds like he sounds like how you remember him sounding from two days ago when he was still alive. The casually delivered growl that sounds like a man who has lived and also very much always almost not lived throughout most of that living...

Sorry I’m making a singer’s life about me but that is the deal. You sing about your life and I take it to be about my life and then I write about it and the people reading that take it to be about theirs...

People love to respect a person on the day they die but then it diminishes incrementally over time unless they were a very big deal. Lanegan seems like the type of guy whose stature will grow after death though I’d imagine. People who sing about death and pain a lot become more important when they’re gone because now it seems like they’ve completed the final course prerequisite. It all feels even more authentic now.

Alright here's me and Oakes. We spoke on Friday at the Harvard Book Store in Cambridge. As always please consider subscribing to support this newsletter please and thank you.

I just want to congratulate John on a remarkable piece of work. I don't know if people have had the chance to read it yet, but it's really extremely well researched and it's almost, in a way, a sort of history of the world through the lens of fasting.

So John – and I'm just going to look at my questions on my phone here, I'm not checking my email – it strikes me as somewhat ironic that in writing this book about depriving oneself of food, you seem to have gorged yourself on reading, on research, on the vast knowledge of human history. When I was reading this I realized that I am very stupid. I don't know how you do this sort of thing. Is that something that came easy to you, or was it a style of research that was abetted by the very lack of food?

Well, first of all, Luke, I want to thank you very much for being here. I really appreciate it. To have somebody like you, you've written a lot of books. So this is my first one. So you've been through this before.

Well, yours is much better.

That's just not true. So to try and answer that question, fasting for me, the experience, I guess the analogy is, it's kind of like a lasagna, you know, that you have one layer and then there's another layer and then there's another layer, and then all together they form the dish. So fasting, as I got into it, and as I researched it, and as I experienced it more and more, it seemed to have all these different layers that come together in this remarkable experience, which for me was really… enlightening might be presuming too much, but it really was empowering, at the very least.

There's a line in the book, “as fasting works to disconnect us from the physical, it reconnects us to what makes us human, our thinking selves.” And, as you illustrate, there's a strong thread throughout history of fasting enabling just that for many people, revealing truths, often divine truths, supposedly. Is that something that you touched at all?

I don't know about the divine truth, but for me fasting is a way to get off the treadmill of daily life and to take a pause in the run of things. And as you know from the book, I'm interested in long term fasts. I'm not so keen on intermittent fasting, though I know a lot of people do that, I think it would be much harder. But to come back to your question, it enables you to get yourself out of the run of things, and maybe even approach a level of serenity. We're so caught up in the deluge of experiences, that fasting is a good way to take a break and to take the measure of things, and then also along the way to think about what you're consuming, what you need to consume, how you consume. And then you go back into everything, and if you're like me, you forget what you've learned during fasting, and so then you have to do it again in a few weeks.

I guess you might say it's almost a temporary enlightenment.

That happens to me when I smoke marijuana. There's a part where you can feel your senses sort of sharpening in a way. You're smelling food from far across a room. Is that your body trying to alert yourself to the presence of food would you say? Is that something that we might have biologically, we might have adapted to? We’re scavenging, and we're hungry, and the senses might sharpen. There's some berries over there, we can smell berries from across the woods, or what have you.

Yeah, I obviously don't know how it came to be, but the way a long term fast starts, at the beginning, this thing called your enteric nervous system, which is, there are about 100 million neurons in your stomach and intestines, and that's sometimes called the brain in the stomach. At the beginning of a long fast that starts yelling at you and saying, what are you doing, you've got to get me some food, you have to go hunt an antelope, and eat it real soon. But then after a couple of days, two or three days, that sort of tamps down.

And then you get this, really a cocktail of really interesting chemicals that your body starts issuing, and it is true that your mental cognition improves. Some people say that… Caesar Chavez, who was a big faster, you know, the labor leader, he said that his memory became crystal clear and he could recount entire conversations word for word. That did not happen to me, unfortunately. But it is true that you do feel… certainly your sense of smell improves. I think it's important to emphasize that it's going to affect everybody differently because we all share certain characteristics, but we're all marvelously different. And so fasting is going to affect each person in slightly different ways. But it is a medical reality that you get this sort of clarity, which is really neat. You get a heightened level of this hormone that's sometimes called the happy hormone, serotonin. There's a molecule called BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which is involved in cell regeneration. There's stuff called Orexin-A, which has sort of a caffeine-like effect, and that starts kicking in. Chemically your body starts to change, and this is all speculation, but I guess the evolutionary reason for that is, sure, it's to give you extra strength so that after this mini famine you've imposed on yourself, you can go out and hunt those poor antelopes.

It almost becomes like your Spidey-senses, like you’re Spider-Man. You mentioned Cesar Chavez. He was at odds with Gandhi about fasting or…

No it was the opposite. One of the really cool things about fasting, as I was researching the history, is that it pops up all around the world in all sorts of cultures, and it's going on all the time. You couldn't get two people from more different cultures than Chavez and Gandhi, but Chavez was very aware of Gandhi's history. And like Gandhi, interestingly, in both cases, they started a long-term fast against their own supporters. In both cases it was to convince them that violence was not a good tactic, and they couldn't convince their followers, and so they undertook a fast. There's something about fasting which conveys a purity of purpose, and it sends a message that in an extreme fast, obviously, not the sort of casual fasts some of us do, that you're willing to put your life on the line, and that of course also is some of the impetus behind hunger strikes and fasting for purpose.

I should emphasize also that when I do it, I don't do it for health, I really do it to achieve some measure of spiritual serenity. But not for religious purposes.

And how many times have you gone back now?

Since I started doing it, I guess I do it for a week at a time twice a year. Plenty of people do it on a regular basis. I think it's also very important when we're talking about fasting to remember that you're flirting with something that potentially is very dangerous. I don't really think people will slip into anorexia, which is a mental disorder, which has really genetic roots. But I think also you don't want to sort of see how long you can go. I mean, it can be very dangerous. People do die, you know, after a few weeks, your body starts to break down, goes beyond the fatty tissue and it starts eating at your muscles, and eventually it's going to eat at your heart. Usually when people are on extreme fasts and they die, it's because of heart failure. So that is something we all want to avoid. But fasting, I really am convinced that it can, even if you don't fast at all, just thinking about the process, I think you can benefit from just thinking about what it means when we unthinkingly consume. I'm going on too long.

No, no, that's great. You got the legal disclaimer in there. If anyone here fasts, it's your own choice. You talk about how fasting can be done for moral or political or health-related reasons. Maybe you could delineate those with some brief mentions of some of the more famous examples.

Sure. Fasting first pops up, an argument for fasting pops up among the Greeks starting with Pythagoras. Around the same time, Buddha, around 500 BCE, he decided to give up all his wealth and the privileges that came with being a prince, and he fasted for 49 days. Which, by the way, I think might not have been incidental, because it showed he could fast longer than Moses. I think also Elijah in the Bible fasted for 40 days. But then he came out of that deciding that was not the way to go, an extreme fast was a bad idea. But fasting is still very important in Buddhism as a way to sort of take the measure of what you're doing, but they don't advocate this extreme fasting.

So from there, Buddha is the most famous faster until around the same time Achilles also fasted. There's so many people who've undertaken fasting. Achilles fasts after the death of his partner Patroclus, and he does it as a way to prepare himself for battle. In fact that also pops up in the Bible. The Jews often fasted before going into battle and slaughtering everyone, and I think in those cases, a fast is kind of like a personal sacrifice. So there are all sorts of reasons to fast, but there are obviously different currents.

Basically every figure throughout history that I'm aware of appears in this book as having fasted at some point. And it's just kind of remarkable the way you were able to pull all those disparate cultures and periods of history together. I really like this part where you say “fasting is by its nature anti-authoritarian.” And as it relates to hunger strikes you make the point that a hunger strike can only be directed upwards. You can hunger strike against your jailers or your politicians. A king can't go on a hunger strike against their subjects. So talk about that a little bit. About the way hunger strikes and fasting are intertwined in the sort of anti-authoritarian nature of it.

I think hunger strikers would agree that a hunger strike is a method of last resort. It's a way of demanding dialogue when either you’re in jail, or, for example, the Sunrise Movement, a group of young climate activists, they went on a hunger strike in front of the White House. It's because they felt they weren't getting their message across. Or the the Irish hunger strikers of the 1980s, the most famous of whom was Bobby Sands. I spoke, actually, to somebody who was in jail with Sands at the time. I asked him if, when they entered into the strike, if this was not a suicidal impulse. And he reacted very strongly to that. He said, absolutely not. We were young men. We had our lives ahead of us. We were healthy, and we had no intention of dying. But we wanted to be heard. And, you know, the nature of jail is that your rights are stripped away, and there's nothing left, you are somewhat exiled from society. In that situation a hunger strike can be a very effective way to force a dialogue. Because either you're being ignored, and then you're left to starve, which says that the authorities aren't doing their job of keeping you alive and punishing you, or they start force-feeding you.

Force-feeding, as I'm sure some people here know, I know there's some doctors in the audience, is a very, really a brutal process, extremely dangerous, and can easily kill the people it's supposedly meant to keep alive. I think several people have died from force-feeding because, you know, they forced them. I won't go into specific details. Really, it's awful, but you can puncture your internal organs very easily. And by the way, just a footnote, the largest hunger strike, mass hunger strike that I came across, was the one at Guantanamo Bay. I think it was like 158 prisoners went on strike simultaneously demanding to be tried or set free.

Also an important point about a hunger strike, is that often they are unsuccessful in the sense that, you know, people… obviously Biden didn't come out of the White House and say I'm going to agree to all the demands of the Sunrise Movement. Bobby Sands died in jail. There are many, many examples of hunger strikers who've had to stop or who died. But still, it gets a lot of attention to the cause. And also when a hunger strike is done together with other people, it acts kind of like a binding agent. It's a physical way to express solidarity with one another.

Yeah, I was gonna say that it's probably no surprise that force-feeding was used quite a bit in Guantanamo Bay. One of the more despicable periods of American history in a while. I find it strange that sometimes… Maybe just because I'm so cynical, and you know the things that I write about power and stuff, but I found it strange how often the powers that be, jailers and so forth, seemed to actually give a shit that people were going on hunger strikes. That doesn't seem like anything I know about power. Were you surprised as well to see that it sometimes works?

Yeah, I was surprised, but it's logical, because the origins of the fast are that you're allying yourself, or you're trying to approach some sort of moral purity. Fasting really is connected at its root in sacrifice and giving something up.

If you're a prisoner you're supposed to be pretty despicable. You're somebody who's wronged society. But also, as I say, you're very subtly, and in a nonviolent way breaking the rules. So this is very upsetting to the authorities. I think you're probably thinking of… Margaret Thatcher was really furious when the Irish patriots went on hunger strike. By the way, there was a long tradition in the 20th., century of Irish rebels going on hunger strikes. But it really wasn't until Sands that something really seemed to have a huge effect, at least on an international level.

But yeah, it is a powerful tool, and it goes back in Ireland to a pre-Christian tradition. There was something called a troscead, where if you felt you were wronged by, say, somebody owed you a debt, and they wouldn't acknowledge the debt, you would go and fast on their doorstep. And then they had to acknowledge the debt, or else they fasted in turn. And so you'd have these kind of fasting duels. And fasting was taken very seriously. In ancient Ireland there were laws against illegal fasting because it was seen as opening a door to a spiritual realm. It was almost a, I hate saying this, but it was almost a magical tool. I think, you know, you get a little residue of that today too. If you fast for a while, you do go into this sort of weird realm. I don't know if it opens up a spiritual realm, but it does take you out of yourself and into some other place, which is interesting.

I love that. The image of fasting against someone. You think of fasting as something you're doing to your own body, but it's way of saying, you know, attention must be paid.

Yes, absolutely. And that's also done in India now. I think it's called sitting in Dharna. Politicians do it, people do it because, you know, the roads aren't being repaired, the police are brutal, and that's a sort of a predecessor to what we know as a hunger strike.

There's something related, another form of protest, to the hunger strikes that we're talking about. You write about how boycotting comes from a similar place, because it's a political action that is defined by not doing something, not purchasing something, not eating something. So where do those two things intersect?

Well, absolutely. I feel the boycott comes straight out of the fasting tradition. And of course, it comes out of Ireland as well. And Captain Boycott was known as a particularly cruel… he was English and he was a particularly merciless rent collector for the...

Can I just ask real quick, how many people here knew that Boycott was a guy?

No one! And his famous rival was Captain Hunger Strike, right?

So Captain Boycott was an Englishman and his job was to collect the rents for an absentee landlord who was some earl. And this is in, I think, the mid-19th century, not long after the terrible Irish famine, which killed at least two million people. So that set the stage for this. At that time, there were many English landlords, and what was grown in a devastated land was being exported to the profit of the landlords. So at some point, and it's not quite sure who organized this, but I know the famous Irish patriot Michael Collins was involved, people decided to shun Boycott. When he went into town, people would turn their backs on him, when he or members of his household went to buy stuff, people would just pretend he wasn't there. There was no violence involved. Also they refused to work for him. Boycott was outraged at this treatment. And if you look at the English papers at the time, he wrote letters, and the English were very sympathetic to poor beleaguered Captain Boycott. They raised a whole bunch of people who volunteered to go and help him harvest his fields and make sure he did his job properly for the absent earl.

This was the origin of the word boycott. And like fasting, it is, I think, a form of fasting, a withholding, or a refusal to accept somebody as a part of the community. Also evoking a moral authority, saying, we are not going to have any dealings with you, and our method of action is to step back.

You also found that there's something anti-consumerist about fasting. You found yourself sort of released, in a way from, you know, think about how many times in a day when you're out in Harvard Square, you buy coffee, you buy Dunkin Donuts or whatever. We’re always purchasing things we may not even necessarily need. So you found a sort of political righteousness to it as well, would you say? You know, like, I'm stepping back from the capitalist grind, just for now, but in that there's something that you get out of that.

Yeah, I don't know if I'd say righteousness, because I hope I don't think of myself that way. But it does have a material effect on you, because suddenly, even if you're fasting for a few hours, you're not consuming. And so you've got to fill up that time somehow, and maybe you're reading, or you're thinking about stuff. But our normal mode of being, especially, I think, in this country, is to be active and doing things, and that's, I mean, because we're human, but that's here I think expressed by buying things. And all the time we're buying things, and that's really been a feature of the last 120 years. After 9/11, president Bush told us that what we really ought to do is go out and buy stuff, which is something I still… I mean, that really is quite a way to mourn. But in a way he was right in that it gets your mind off of deeper things, and maybe more on things that are superficial. And to go back to the superficial, it's important that you buy things, of course, buying books is on the level!

Yes buying books is important. Let’s not go too far.

Woodrow Wilson was a big promoter of that idea. There's been, I know you're tougher on this stuff than I am, but I mean, there is a capitalist imperative. If you don't buy, the whole machine stops. What I found that was interesting was that until really the latter part of the 19th century, American presidents would often call for national fasting days. In moments of crisis, or when there was some natural disaster. I think Abraham Lincoln called for three days of fasting. What he called fasting, humiliation, and prayer. He did one after the Union lost the battle of Vicksburg, and he issued a national proclamation saying that we had grown full of ourselves, thinking about materialistic things, and it was time to pause and to think about what we valued and why. I thought that was interesting that that stopped. Certainly I'd be shocked if any president called for a national day of fasting. It’s inconceivable that that would happen.

No, I can't imagine that at all.

I don't think Trump would call for fasting.

We'll see! We talked a little bit about Ireland and India briefly here, and you point out that parts of the world that have a history of famine also have a rich fasting culture. Ethiopia too. What do you make of that?

I think that's one thing to ponder. Fasting doesn't necessarily mean that you have a lot to eat and that you have a lot at your disposal. The ability to fast and the decision to fast, and this goes back to a question you were asking a little earlier, that it's such a personal matter, and it's an act of agency over, asserting control over your body in a way.

But to come back to the idea of these countries which have these terrible famines and at the same time have strong fasting traditions, I think it emphasizes that the power of fasting is that when you come out of it, you really, without being sort of self-satisfied or self-praising, you really appreciate what you have at your disposal, as little as it might be. And you value it, and you think about how you're going to use those resources. It's certainly striking that the traditions are so strong in both Ireland and India and Ethiopia.

What you just said there about being conscious of what you have and what you don't have when you make the choice, it reminds me of the part where you talk about the Lysistrata. And you write this line here.

I knew you were going to talk about sex, Luke.

I'm sorry! Sorry. I was trying to be clean here. You say “withholding sex is distinct from simply not having sex in the same way that fasting from food differs from experiencing a famine. The potential of sex hovers over all discussions.” So the point here, and it sounds obvious, but there's a big difference between starving and fasting.

Starving is something that can be imposed on somebody, and unfortunately is all the time around the world. And now many people are going hungry. But fasting, you have to make a decision to do it. Even if you're part of a religious group that's fasting and it's time to fast, nobody can know for sure if you're fasting. It's something that you have to do privately. And that's a powerful thing. I mean, nobody's going to know whether or not you fast, and you don't want to go around boasting about it. But I mean, it's sort of an odd thing.

Or write a book about it.

Sorry! Sorry about that. But yeah, hopefully I don't go around self-aggrandizing in the book. I'm just talking about it.

No, you don't. You don't.

But that's why I think it's such a valuable thing. Also what's cool about it is you don't need anything to do it. All you need is yourself. It's a lot easier, of course, if you have somebody to fast alongside of you, because then you have…

Same thing with sex.

Well. Well said, Luke.

You set me up.

But with fasting, you want a partner because if you're doing the long term fast, the first two or three days are uncomfortable. I'm not going to say painful. But it's a little uncomfortable, and then you can complain to each other about it. How miserable you feel, how cranky. And then you get to this plateau that, as I say, approaches some level of serenity. And that's kind of a neat place to be.

But I'm not sure I answered your question.

That's OK. I don't remember what it was. Something I found fascinating was the sort of gendered nature of fasting throughout history. And it seems it sort of seesawed back and forth over time in different cultures. Christian ascetics, there was a particular feminine aspect to it. And then in later cultures it was considered to be a sort of masculine show of power. Elaborate on that a little bit. And then if you can talk about how it relates to how we think of disordered eating in contemporary times. And that has a sort of gendered aspect to it, for better or worse.

Yeah, I'll try. That's a multi-layered question. But for me, the process of fasting is it almost de-genders you. Because it's not a sort of a – and I’m going to slip into gender here – a “masculine” thing. You can't win fasting. There's no goal. It's just a period of withholding, that has to be accompanied by contemplation. And it moves away from a gendered space. I think that's an interesting aspect.

In the Middle Ages, it seemed to be the province, largely…there were a ton of fasting women saints. And then the church put a stop to that and said that you couldn't achieve sainthood through fasting. But I mean, you had people like Catherine of Siena who was one of the church's most holy figures, and who fasted all the time, and of course died probably of starvation in her 30s.

But for whatever reason, the church decided that this was not a path to spiritual enlightenment. But fasting continues to pop up in the west certainly. And you get this phenomenon known as “fasting girls” from the Renaissance up through the 19th century. People would pay to see these fasting phenomena. And I think many of them probably were anorexic. Some were, I think, were clearly fraudsters. But it was associated with, as I say, with girls, with women.

This is speculation, but it was associated with women as being sort of the so-called weaker sex, leaving aside the fact they go through childbirth and all of that, that we don't talk about. We just are thinking of them as lying there pallid on a bed and at the mercy of stronger people around them. And then that starts to shift, and in the mid-19th century, you get these fasting show people, like Henry Tanner, and there are whole bunch of them. People would pay a lot of money to see people fasting, and you just paid to watch them fast. Kafka's Hunger Artist comes out of that. That continued right through the 1920s.

You mentioned fraud. It struck me that there was so many of these fraudsters, as you say, but how different is that from some of the fad diets we have now? And there's all these different fasting trends, particularly among tech type guys who are doing these fasting things now.

It is fasting, but for me, it's not a really interesting kind. It's sort of fasting as acquisition, because you're trying to, in the case of people who are convinced they're fasting for much better health, you're really thinking about trying to become a super person. And there's all this stuff about hyper wellness. Fasting, it's important to emphasize, that when you stop fasting, your body sort of goes back to what it was. You should not fast in order to lose weight. That doesn't work. Up to 80% of our body weight is determined by genetics. And it's just a bad way to… you won't lose weight, except temporarily, if you're fasting. And yes, there are places where you can go and pay thousands of dollars a day for the privilege of having food withheld from you. That's not a necessary. You don't really need to do that.

All right, well, I think I was going to ask you to talk about the first thing you ate after you ended your fast, but you know what, maybe we should tease that and say you have to read the book to find out.

It's been ten years since the release of this work of Worcester, MA excellence. What a song. What an album.