I don't care where just far

I was looking through some old boxes of shit that I finally took from my parents' house a while back and it reminded me of a piece I wrote about the experience of going home to clean up your history for Boston Magazine a couple years ago. I decided to remix that piece and post it again and by remix I mean go in and take out all the commas and add in some updated jokes. You can jump to that one directly here but I'll also include it at the bottom of this newsletter as well.

Here was someone writing under my name in a voice that no longer exists and what was worse speaking at length and with no shortage of emotional conviction about things I no longer remember ever caring about. I felt the same way about the dusty boxes of memories. A strange dissociative feeling like none of this had ever happened or had happened to someone else. Someone who wasn’t me. Reading some of the old letters and emails felt like eavesdropping on conversations that I wasn’t meant to hear or at least that my clearance level should have been revoked for by now.

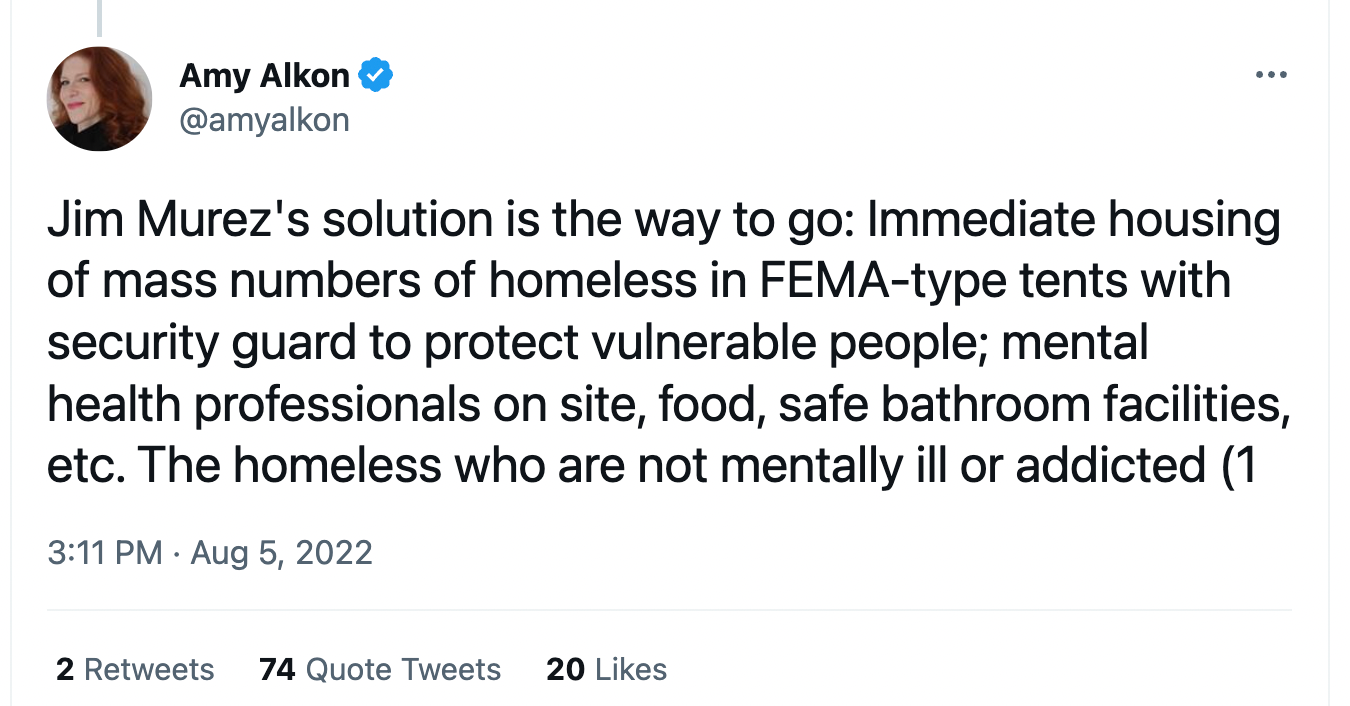

Today's feature is an appropriately furious response to the latest attempt to solve The Homelessness Question. Andreina Kniss writes that there's no such thing as a humane concentration camp. It's an idea you would think wouldn't need to be explained and yet here we are.

What if we sorted, or concentrated rather, undesirable and unsightly people into a sort of bivouac, or camp I guess you could say, in lieu of burdening property owners from being inconvenienced by their loathsomeness. https://t.co/Zs9VPIpdqA

— luke (@lukeoneil47) August 5, 2022

I spoke with Kniss a while back about her work with homeless outreach group KTown For All.

If you appreciate what you read here it would be great if you could help pay for it.

A Kinder, Gentler Concentration Camp

by Andreina Kniss

Another day, another attempt to solve the issue of homelessness by rebranding the concept of concentration camps. The latest iteration of what’s become a distressingly popular trope, particularly here in California, came from basketball commentator and former NBA star Bill Walton. Walton is a revered figure in the world of American sports, in no small part due to his status as a bona fide icon of the 1960’s “counterculture.” He’s known for his idiosyncratic, freewheeling style in calling college basketball games (think Joe Biden channeling Jerry Garcia), and as such you would like to think, even though we know better, that he’d know better. But true to form in that aging hippie style, he couched his proposal to build open-air concentration camps for the homeless – to be operated by his personal non-profit naturally – with a sense of compassion.

With these people it's always what the unhoused are doing to you, the upright protagonist of the neighborhood, by forcing you to notice them existing, instead of what has been done to them.https://t.co/Pu8nOrvvyO

— luke (@lukeoneil47) December 21, 2022

But Walton predictably finds compassion primarily for those who, like him, have to look at the homeless, and observe the deplorable conditions they suffer through in the streets of America’s cities. As usual, compassion for those actually suffering, the unhoused persons that our leaders have essentially abandoned and left to die, is in short supply. Walton decries the “lawlessness” of current day San Diego (a city experiencing some of its lowest crime rates in decades), and lays out the plan that he and other heroic San Diegans have taken up to Do Something About It. Meet Sunbreak Ranch, an as of yet empty tract of desert land on which Walton proposes to set up a mega-shantytown that San Diego can just ship all those nasty homeless people to.

Writing in The San Diego Times he describes it like so:

"Individuals can reside in a community tent, or camp on their own in a series of designated and protected areas for families, single mothers, elderly people, veterans, those with dogs, and others as needed. Sunbreak Ranch will span 2,000 acres with vast open space surrounding it. There will be portable toilets and portable showers, mess halls, medical tents, storage facilities and onsite service providers including dedicated teams of mental health professionals, substance abuse rehabilitation specialists and vocational trainers. There will be free daily shuttle service going to and from downtown San Diego — only 12 miles away. Sunbreak will have private security as well as a permanent 24/7 public police station in order to maintain a “clean, healthy, safe and secure environment” for everyone at all times.

Of course, this crisis must be “managed humanely, compassionately, and within the context of a civilized, law-abiding society.” Radical, dude. Who wouldn’t want to relocate to a tent city in the middle of the desert, where you’ll be segregated based on factors such as your age, marital status, past military service, and…pet ownership? And there will be mess halls too?!

But despite the false promise of services, freedom, and care, the stark reality underlying this fantasy is the forced removal of the unwanted from society. We the civilized (housed), stay here while the uncivilized (unhoused) go over there. Somewhere we don’t have to think or look at them, and where they can learn some respect for the Rule of Law. It’s forced separation of those people whose visible destitution spurs unavoidable cognitive dissonance for passersby who instinctively recognize the injustice that some should have so much, while others suffer and die in the streets of the wealthiest nation in history.

The dissonance is the issue being solved mind you. Not the suffering.

Importantly, the people seeking to profit from the crisis of homelessness by pushing for more mass incarceration and displacement, like Sunbreak Ranch chairman George Mullen, the co-author of Walton's op-ed, know how to spin it so all of the worries of good polite liberals and former hippies like Walton are quelled. They often say something like “This is to keep us and them safe. This is for their own good. This isn’t a concentration camp, it’s a community.”

They’re not imprisoned, they say, they just have to live in the camp and follow all the rules under 24/7 police watch. It’s not carceral, it's regimented tough love. “We have tried everything else and nothing has worked,” they say. “This is the only option we have.”

I happen to agree with Walton that it is inhumane to allow human beings to sleep, urinate, be assaulted and raped, and ultimately perish on our city streets. But Walton and Mullen seemed to have overlooked the solution staring them and America’s political leaders in the face:

HOUSE THE UNHOUSED!

House them in real apartments and homes, not on a campsite off a freeway in the desert.

For $0 I will tell you that “lack of housing / affordable housing” is the main issue and you can spend all $30mil on building new housing pic.twitter.com/C5tZl5u8c6

— Tyler Littwin (@ProfTBLittwin) January 18, 2023

Bill Walton is not the first nor will he be the last person to suggest massive displacement and exile of the unwanted. Displacement and incarceration is as American as apple pie. Slavery, the reservation system for Native Americans, segregation and redlining, forced institutionalization, the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II; the list goes on and on. Presently, you can tune into any Los Angeles City Council meeting (or any city with a large unhoused population, really) with a public comment portion. You’ll hear the “push them into the desert” or “arrest them all” idea shouted at least a couple of times per meeting. It’s the natural conclusion after being bombarded with lies from politicians and the media that the unhoused have plenty of help and services, but that they’re somehow faulty people who refuse this plentiful help due to a character flaw universally present in the unhoused. Speak to any unhoused person on the streets of LA and you’ll hear stories of being on dozens of waiting lists for housing who have told them to check back in a decade or two, of wanting a detox bed to get clean only to be told it will be a month or two before they can get a bed, of their belongings getting thrown away during sweeps setting them back and forcing them to start over every time.

The reality is we have tried nothing that addresses the housing market that leaves people without a home. Nothing but punishment.

The discomfort of seeing the unhoused living in squalor leads many to a crisis of conscience. Most don’t have the language to recognize the fact that the people on the streets are purposeful victims of capitalism. And none of us “regular folk” want to think about how close each of us really are to finding ourselves out on the street, struggling to survive. So we end up telling each other that it's their own fault, or that these people live on the streets by their own choice. We end up concluding that the unhoused are bad people who purposely shun the plentiful help available. That we have so generously offered. In this alternate reality, recreated daily by city leaders looking to avoid accountability for the ballooning of the unhoused populace, it is the homeless themselves who must be fixed. No further analysis of our economic system or societal values needed. It’s a comfortable and conscience-easing conclusion. And when you come to believe it, then you can be reconciled to the idea that your unhoused neighbors are not part of your community at all. They are threats to society rather than victims of its fundamental structures.

It is also no coincidence that the desert is always the chosen location for these concentration camps. California has a knack of pushing all things bad into the desert. The high desert is a landscape of agriculture, concrete, massive warehouses, truck stops, meth, poverty, exploited migrants, and vast expanse of nothingness. This is in juxtaposition to the lovely picturesque coastline where 80% of the state’s residents reside. The desert is our waste bin where nuclear testing, military bases, and industry goes to hide. Most Californians’ singular exposure to the desert areas occurs only when they drive to Vegas. It is a whole different world out there. Out of sight out of mind. And it is no surprise that the desert is already where unhoused people are ending up. After cities have taken the position of criminalizing the unhoused, people are pushed out further and further, out where they can get some sleep without being awakened by a cop handing them a ticket for being poor on the street that they’ll never pay off.

To address and ultimately solve this crisis requires a process of societal self-reflection and a reimagining of our entire economic system. This is not only hard to imagine for most people, but directly conflicts with the interests of the wealthy like Walton and Mullen. Not one proponent of the mass displacement and incarceration of the unhoused has been able to explain why people cannot simply just get treatment and housing here in society with the rest of us. Why is building a homeless-only camp in the desert more realistic than building an apartment building in a city where there is space and plenty of vacant units and empty hotel rooms? Why do they have to leave? If we can’t help them adequately now in a city environment with all of the resources it holds, why should we trust that Sunbreak Ranch can build a flawless support system with a fraction of the funding opportunities in the middle of nowhere where it is regularly 100 degrees? This is not to mention the complete dehumanization that takes place when you refuse to recognize the unhoused as people with friends, family, jobs, and doctors in the city they might need closer access to, social connections that they’d like to preserve. Instead they are infantilized with a smug paternalism that the wealthy excel at. They don’t take the time to talk to these people, and certainly not to listen to what they need. To them, the crisis is an opportunity to make a buck off government contracts. They know what they need; it's a prison camp, and it doesn’t matter where it is as long as it's far away from here.

Andreina Kniss is an organizer at KtownForAll, an all volunteer unhoused rights and outreach organization that supports and advocates for the unhoused community in the Koreatown Los Angeles neighborhood.

Kind of at a loss for words for this next bit but here we go anyway. On Tuesday of this week the Republican Women’s Club of South Central Kentucky held a fundraiser in Bowling Green. The guest of honor for the event was a man named Jonathan Mattingly a now ex-Louisville police officer who you may remember as one of the cops who killed Breonna Taylor (and was shot himself) when they raided her apartment in March of 2020. Mattingly published a book last year detailing that night titled "12 Seconds In The Dark: A Police Officer’s Firsthand Account of the Breonna Taylor Raid" which was published under an imprint of The Daily Wire! In it he continues to blame Taylor's boyfriend Kenneth Walker for everything that happened.

This is all bad enough already but it gets worse.

After the original host of the event canceled it because of controversy over Mattingly's appearance and a Republican candidate for governor pulled out another location was found at a place called Anna’s Greek Restaurant according to Spectrum News 1.

What happened at the event is where this all goes from routine nightmare Hell World shit to another level I wasn't really prepared for.

So apparently one of the cops who killed Breonna Taylor was invited to a Bowling Green restaurant by a GOP group, whereupon he played footage from the raid on Taylor’s apartment to a restaurant full of people who were unaware he would be holding an event there pic.twitter.com/aJV0fxadNm

— Tarence Ray (@tarenceray) January 20, 2023

They held a fucking screening of footage from the night Taylor was murdered by one of the guys who did it.

Like a fucking director touring his little short film.

All the while regular diners unconnected to the event were unwittingly subjected to what was happening according to the Bowling Green-Warren County NAACP.

"These patrons had to see and listen to graphic descriptions of the incident which killed Breonna Taylor because Mattingly was provided video equipment, a microphone, and a speaker and was able to be heard throughout the restaurant," a statement the group put out yesterday explained.

"It was impossible to hear each other over the sound system blaring above and the applause," one diner in attendance wrote on Facebook.

I will never eat at Anna's Greek Restaurant again. What started out as a wonderful evening with friends, morphed into...

Posted by Cayce Johnson on Tuesday, January 17, 2023

"They also expected us to be quiet as we dined below. Then the bodycam footage started. These people had paid $40 for a buffet and a cash bar, to sit down and watch the final minutes of an innocent victim's life while they supped. Breonna Taylor was murdered and these people were celebrating her murdered and his new book."

The Republican women's club sent a statement to Spectrum News. “These events may be controversial, however, we believe Sgt. Mattingly has the right to share his experience…” they said. “Other individuals with firsthand experience relating to this case are welcome to request an opportunity to speak to our organization as well.”

That sounds good. People should definitely go and speak to them.

How to Throw Your Life Away

The ceiling in my childhood bedroom is so low. You could jump and hit your head on it and knock yourself out if you really wanted to. You could break your neck. I'm not going to do that but I could is the idea.

The room itself is so small too it feels as if the walls are closing in. Part of that might be the way that everything in the home you grew up in seems smaller when you come back to it as an adult but it’s also probably because when the room was built a few hundred years ago people didn’t have as many useless possessions to hold onto forever as we do now.

They were a lot shorter then too in general hence the ceiling situation.

The guy who built the place back in 1766 was a son or a grandson of the first governor of Plymouth Colony. If that makes it sound like it’s some fancy preserved historic home or something that people would want to come look at it wasn’t it was a piece of shit when we moved in in the 1980s. There was an actual outhouse still attached to it and the room where my mother smokes her cigarettes now didn’t have a floor back then it was just dirt.

There’s a big rock out back with a plaque on it to commemorate the historic significance of the area anyway but I forget most of the details now.

They were born and then they lived and then they died.

I used to climb onto the rock when I was young and unbothered by history standing on top and looking out at the farm next door that had a total of one horse and one cow. It always seemed like the loneliest farm in the world to me but maybe it was just an exceptionally efficient one.

Every year around the start of spring I get a call from my mother asking me to come contend with the entire history of my youth which has been jammed into this room for almost twenty years. It’s like the persistent alerts you get on your phone saying you’re running out of photo space and it’s time to upgrade your storage but even phones don’t (yet) have the power to guilt you into action like mothers do. This year I finally gave in. I was in the neighborhood anyway to celebrate the birthdays of my niece and sister two people at various stages of their own object accumulation so I trudged up the alarmingly steep and uneven staircase where the wood of the walls has warped outward under the compounding pressure of the centuries.

Inside the bedroom was a mess. I found box after box filled with the detritus of past. There were old comic books my mother insisted must be worth some money and projects dating back to elementary school and high school and college essays. There too were some morbid poems written in an unrecognizable scrawl that I’d bound together into a book with a flowery wallpaper covering. I must have recently read Emily Dickinson’s “Because I Could Not Stop for Death” for the first time when I made it because one verse was clearly a rip-off. I laughed because at least it was proof to me that I’ve remained consistent in my miserable brooding all these years.

I found a treasure trove of cassette tapes as well including some I’d even listen to right now—Dinosaur Jr., Liz Phair, Alice in Chains—and some I wouldn’t such as a Hootie & the Blowfish live bootleg from 1992. I don’t know what to tell you man the 90s were weird.

Then some postcards from girls I no longer remember and long desperate letters from ones I always will. Pictures of friends whose names are lost to me and pictures of friends who I still see all the time and posters of concerts I’d been to by bands that haven’t existed in decades. There were Boy Scout badges and photos of me and my friends looking like we were in a 90s boy band and photos of my dead friend who actually was in a 90s boy band and photos of people I’d thought at the time would be in my life forever and of course would not.

I found my old shit in other words which feels like an appropriate term because I found it all surprisingly foul.

By coincidence I wasn’t the only person staring down a personal history. A high school buddy came to visit me while I was going through my old things—I’d found a mixtape he’d made me in the pile—and he showed me his latest project. It was thousands of archived emails that our group of friends had sent each other beginning in 1996. At first I was thrilled about the prospect of being able to read what we were talking about back then and I jumped into the messages but the excitement didn’t last long. Here was someone writing under my name in a voice that no longer exists and what was worse speaking at length and with no shortage of emotional conviction about things I no longer remember ever caring about. I felt the same way about the dusty boxes of memories. A strange dissociative feeling like none of this had ever happened or had happened to someone else. Someone who wasn’t me. Reading some of the old letters and emails felt like eavesdropping on conversations that I wasn’t meant to hear or at least that my clearance level should have been revoked for by now.

It all engendered something like a sense of revulsion.

Throw it all away I told my mother. I don’t want any of it. It’s not mine I said which hurt her feelings something I seem to be very good at doing lately. Why wouldn’t I want to dig through it all for hours and pick out the things I want? she asked. The honest answer is I don’t know.

The repugnance I felt for my belongings seemed off to me. Based on what I gather from the famous Netflix show about organizing – which I haven’t seen but have read roughly 10,000 posts about so therefore am an expert on – it’s supposed to be hard for people to let go of their sentimental clutter right?

I asked some other people how they felt about the process of spelunking into their own historic bullshit.

Cara Hogan of Malden told me she’d been tasked with a similar project by her parents recently. She rediscovered an old Walkman with her first cassette (Whitney Houston) and a pair of vintage white Vans she said she’s going to start wearing again plus some old Bath & Body Works raspberry perfume.

“I took one sniff of it and flashed back to being an awkward 13-year-old,” she said.

“But best of all were the folded-up, triangle-shaped notes my friends and I passed back and forth in school that I had saved.” She laughed at the notes and took photos of them to text to friends and tossed the things she didn't want like band T-shirts she had purchased at a mall so long ago the mall doesn't even exist anymore. Most of them don't I suppose.

She tried to be brutal she said but had trouble letting go of things such as letters her friends wrote her from summer camp.

She didn’t share my disconnect she said but the process of digging through those belongings did play weird tricks on her brain. “I felt like every small, odd artifact I found opened an old door in my mind that I hadn’t opened in years,” she said. “I do feel like part of me is still that awkward, shy girl who spent most of her time reading…. I may be getting older and gray, but I can appreciate where I came from and where I’m going now.”

For others sorting through old things can make their memories feel more fragile. A couple of years ago when she was about to move to Ohio Nick Maggiore’s mother came to Watertown to drop off a station-wagon load of his stuff. There were school papers dating back to third grade and tapes from 1988. “I went through everything and tried to remember the stories of these things,” he said. “I tried to think of the reason my mom would have kept them.”

The more he looked at the things though the less real his memories actually felt.

Broken instruments and tapes went into the trash he said and old toys went to thrift stores in the hopes that someone else might be able to make new memories with them. He sold enough Magic cards to fund a vacation to Italy he said which makes me think I might have screwed up just now by throwing most of my collectors’ items away. I really should listen to my mother more often.

Maggiore said he put fliers from old rock shows into a binder that now sits above his computer and that he has a pile of role-playing books that he can’t bring himself to toss. “They remind me of old friends and of nights spent rolling dice and drinking Mountain Dew,” he said. “Part of me is afraid that if I give up those talismans of my youth, I’ll forget.”

Of the people I asked only Henry Druschel who now lives in DC but grew up in Boston seemed to share my general ambivalence when it came time to clean out his childhood home. “It did not all feel familiar, which I imagine is why it was so easy,” he said of his old things most of which he happily threw away. He said his sister had gone to college a year earlier and really agonized over what to do with her stuff. “I think she ended up getting a storage unit near her college, which was, and is, bonkers to me. I did not have nearly the same level of difficulty dealing with my belongings and that made me wonder if I was supposed to.”

That’s a good question. Are we supposed to?

Developing attachments to things is a normal part of the human condition although it varies across the developmental stages of life as Jerrold Pollak a clinical- and neuropsychologist at Seacoast Mental Health Center in Portsmouth, New Hampshire told me. But by and large there’s nothing all that peculiar about it. “We can easily get attached to many things that other people would say are irrational and ridiculous,” he said. “A lot of attachments are irrational fundamentally.”

But the process serves certain psychological needs—it helps us cope with and adapt to the world.

People keep stuff for all kinds of reasons. Some do it because they feel loyalty to the person who gave it to them and think throwing the item away would be a sort of betrayal. I have had a number of old letters my beloved grandmother sent me stashed away for over a decade now because disposing of them would feel like desecrating her grave in a way. She doesn't have a grave we poured her ashes into the water off the coast of Maine in a spot that she loved but you know what I mean.

Maybe other people feel that getting rid of something would be a break from the past that they don’t want to go through with?

This impulse to retain a connection with the past is about giving us a sense of continuity over time Pollak said. Where we came from and our roots and our identity. In general this is fine and even healthy he said but there are other hazards to clinging to the past. For some people he said "these are not possessions so much as albatrosses around their neck. But they don’t recognize it."

A smaller number of people go in the exact opposite direction. They want to erase their past and leave absolutely no evidence of it. They get rid of everything. That’s not quite me. I don’t want my past to disappear I just don’t want to have to spend too much time thinking about it. I’ve got just enough psychological damage in the present to keep me busy.

“People who literally incinerate their past, that’s probably a defense against a lot of bad feelings about their life and maybe a kind of almost-revenge against family and experiences from their childhood,” Pollak said. “I think some judicious holding on to certain basic things is important.”

It’s about balance then which is always the boring answer when it comes to anything having to do with psychology. “I think there’s a hierarchy of what feels important and is important and that can evolve over time,” Pollak said. “At twenty you might keep something that had to do with your childhood, and by forty you know this is just not relevant to you anymore. It means nothing to you, and you’re sort of unloading.”

In other words going through old boxes can mean unburdening yourself of feelings that you’ve kept inside for a long time. If that sounds like psychotherapy there’s a good reason. It is in fact why people often seek help from folks such as Carleen Eve Fischer Hoffman who has been a professional organizer for twenty years and runs a business called the Clutter Doctor based in East Longmeadow. Her three-step approach for clients—examine, diagnose, prescribe—tries to drill down beyond emotion into more-practical terms. Take ancient school papers for example. Rather than holding on to all of them pick out the ones that could be useful in the future like papers relating to a degree or with professional value she said. With other items like old books she tells people that if they can find a way to let them go to a good home—churches, schools, veterans’ groups—it can make the transition a lot easier.

None of that means you need to obliterate your past in one fell swoop Laura Moore said. She's another organizing expert who runs a business called ClutterClarity in Concord. Her approach incorporates emotional-management skills. Most of her clients feel crushed by some kind of impending pressure be it a move or a death or a divorce. “That’s enough to flatten most of us,” she said. “There’s a misconception that we declutter one time, once and for all. But you should declutter and organize as your life changes.”

It’s not that the inherent value of an item has changed over time but rather that we ourselves have changed.

Disassociation of the kind I mentioned often exists she said. “It can be a form of resistance,” she said, “but it can also be a form of saying, ‘This doesn’t belong in my life anymore.’”

A few days after I sifted through my childhood belongings I called my mother back to ask her if she’d thrown everything away yet. Don’t I told her. There are a few more things I want to keep. I needed to return to take another pass at editing down my story. I’d already taken some photo albums with me and a scant few books including the Emily Dickinson that had inspired my young doggerel and most likely helped trigger my eternal melancholy.

My mother is a quilter. When someone dies his or her family often brings leftover possessions to her—T-shirts and sweaters and so on—to stitch together into a blanket that they can wrap themselves in weaving together the literal fabric of a life into something tangible. Often times there’s simply too much so decisions must be made. It’s similar to how we have to deal with our own lives as we go along: You can’t hold every memory in your head at once—it would be maddening. Instead we pick and choose which memories to keep sometimes subconsciously or sometimes by deciding that a certain day or a certain interaction or a certain smell or a handful of objects among hundreds will be the ones we think we will want to remember forever. And then we put the rest in a little box somewhere and bury it in the earth. And then one day we crawl into the box too.