How to live an intentional and ethical life

RIP Steve Albini

Today Trevor Shelley de Brauw, a Real Chicago Guy, of the band Pelican and others, returns to write about the too short life and unbelievably prolific work of Steve Albini, a Real Chicago Guy, seeing Shellac, recording in his studio, and trying to live an ethical punk life.

Trevor previously contributed to The Cure top 5 songs series.

Please consider a free or paid subscription to help pay for independent media.

First some preamble from me.

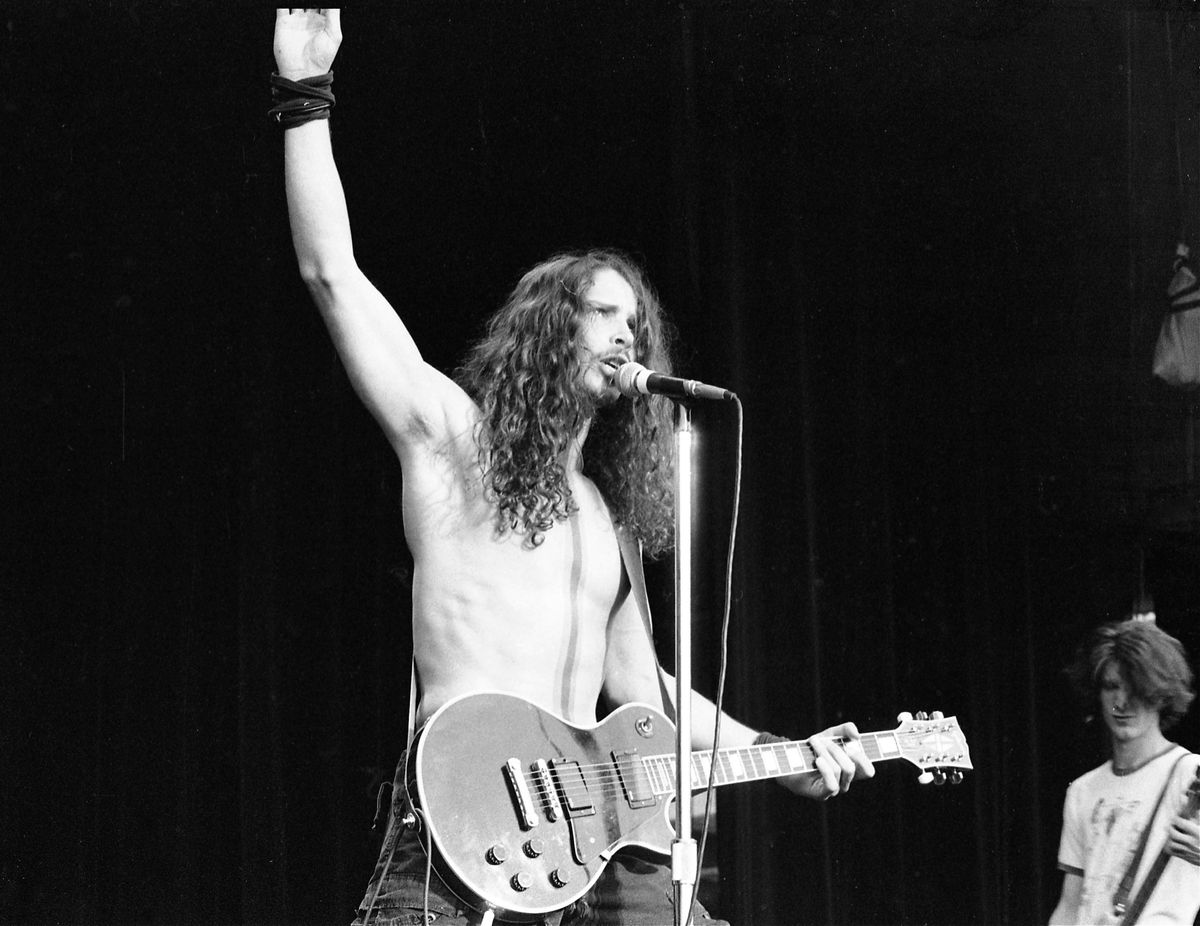

We all love Pod and Surfer Rosa and In Utero and 24 Hour Revenge Therapy and Things We Lost in the Fire and The Magnolia Electric Co. and Rid of Me and Goat, but I'd just like to remind everyone that Steve Albini also worked on Bush's 1996 sophomore effort Razorblade Suitcase and the hit single Swallowed and I sincerely love that song very much. He (surprisingly) admired the band as well and his liner notes for the 20th anniversary reissue of the album are worth reading.

If you read this newsletter you know that it's The Magnolia Electric Co. record for me above all the others though. A perfect record. Farewell Transmission being maybe the greatest song ever written. In Jason Molina's words "one of the most heroic recording moments of all time."

We quoted this story in the Molina retrospective but here it is again from an interview he did in 2010.

JM: “Farewell Transmission” must be one of the most heroic recording moments of all time, because I called in people that were not already scheduled to be in the band and I was like, “Oh, now we’re going to have a violin player, and we’re going to have an extra singer.” I called out all of these things, much like a conductor does – and trust me, I’m not a conductor. I’m the break man. I will not fuck you up if I am the break man, I just don’t want to move anymore.

We put, I think, about 12 people in a room and recorded that song live, completely live, and unrehearsed. I showed ‘em the chord progression, they had no idea when it would end, and we just cut it. Steve [Albini] did a beautiful job. I noticed that at one point when it was a little too loud or a little too soft he came and opened a door to make it work, because it was just an ambient recording. When you hear that song kick off everybody knows it, and what’s so disturbing to me is the way that I ended it is I was dictating to the band and Steve—I go “Listen. Listen. Listen.” And then at one point they all stop. It’s great.

JT: I can’t even believe that was done live and improvised. That is absolutely stunning.

JM: I got all my favorite friends from Chicago, and my favorite, good musicians and we just did this record, and it has lasted. It’s got weight, I’m talking 500 pound weight; something you ain’t going to be able to lift too easy. You have to understand we’re working on a string, and Steve is throwing us a bone, giving us the studio and everything, and we are terrified about how expensive it is and he just went the extra mile. That’s the way it works and that’s where I come from. You get the job fucking done.

There are too many other pieces of musical magic to mention and too many other pieces of writing and posting done by Albini to even begin to capture a fraction of it all but here are a couple of things I saw shared the other day that I wanted to pass along. The first is the famous letter he sent to Nirvana before recording In Utero. The one where he refused royalty points and said he wanted to be "paid like a plumber."

Steve Albini. pic.twitter.com/DzYjvJykdx

— Nirvana (@Nirvana) May 9, 2024

This short essay about the magic of record stores is great as well.

Back in 2009 Reckless asked Steve to write something about record stores for record store day. He agreed & wrote this. We published it in the Chicago Reader as an advertisement pic.twitter.com/mNt2rCNQSe

— matt jencik (@mattjencik) May 8, 2024

Also watch this clip of Albini talking about his views on capitalism with Anthony Bourdain.

Hope these two get to have a reunion and share steak sandos again up there (or like wherever they are).

— L. ➶✧.* (@KatieHawkBishop) May 8, 2024

Anthony Bourdain and Steve Albini at Chicago Ricobene's for Parts Unknown S07E02. pic.twitter.com/QCtMC26Dmp

Here's Trevor. RIP Steve.

How to live an intentional and ethical life

by Trevor Shelley de Brauw

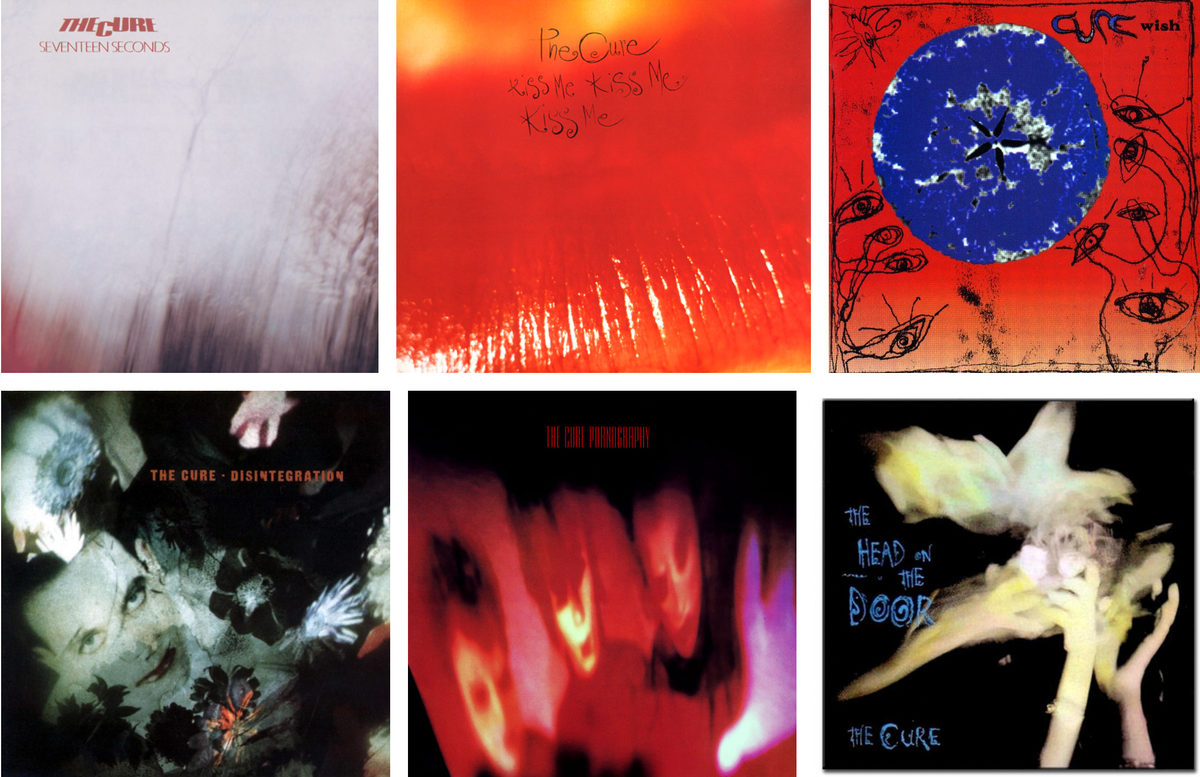

I will never forget the first time I saw Shellac live. They were sandwiched on a bill between Blonde Redhead and Fugazi at Congress Theater in Chicago. It was May 8, 1998, exactly 26 years to the day that the news broke of Steve Albini’s untimely passing at the age of 61.

There were a litany of reasons that the show was unforgettable, from the impeccably curated bill of three bands at their absolute peak, to Fugazi’s Ian MacKaye eloquently eviscerating a heckler that wouldn’t stop calling out Minor Threat song titles, to meeting my future wife (my personal highlight). It was literally a life altering show. But few things are burned so distinctly in my memory as Shellac’s unnerving performance of Didn’t We Deserve a Look at You the Way You Really Are. The band looped the song’s core two-note riff on bass and drums an innumerable amount of times with Steve hovering around the microphone as though he was plotting the perfect moment to strike. Instead he held back and just let it go on and on. At first it settled into a hypnotic groove, with the audience closing their eyes and swaying. But the initial lull gave way to rising discomfort when the short refrain continued to repeat endlessly with nary a note of guitar or vocal in sight. Little by little the demeanor of the audience began to shift as the tension in the room grew palpable and, eventually, subsuming. As the repetition stretched on toward the ten minute mark people started to shout, screaming and pleading for them to stop or to change or for just anything to happen. Inevitably it did, of course, but it’s those long minutes that are crystallized in my memory – the absolute discipline of those musicians and the collective will to torque people’s discomfort to Stravinskyian levels, creating a capital-M Moment that everyone in that room shared, and like me, will probably remember forever.

There’s something of that aesthetic that carries across everything Steve touched, from the recordings he engineered, to the music that he created, to the essays that he wrote, to the conversations that he had, right on down to his acerbic and often hilarious social media posts. At the core of his interdisciplinary work was an unwillingness to gloss over the ugliness and banality of the world. Given his skillset, intellect, and notoriety, he could easily have pandered to an audience, but he opted for a rockier road – willfully shaking people out of a complacent stupor with songs and screeds about the many, many ways we are exploited by those we trust, and urging us all (including himself) to be better, more ethical people.

Though he often publicly claimed not to have an aesthetic as a recording engineer (he famously compared himself to tradesman, like a plumber or electrician), there is inarguably a distinct sound to his work that carries this same spirit – eschewing meticulously constructed productions in favor of capturing the sound of a band playing in a room right in front of you, warts and all. People tend to use words like “raw” or “confrontational” when they’re discussing Albini’s recording work, but those aren’t quite right. He was much less an instigator than someone who commanded engagement; his work asks you to be present, aware, contemplative. His recordings are not a construction so much as they are a moment in time captured on magnetic tape.

The first time I encountered Steve’s name was in connection with his recording of Nirvana’s swansong In Utero. I distinctly remember the music media expressing shock over the choice, given that Nirvana were at the peak of their popularity and set to record the follow up to Nevermind, which had upended the landscape of mainstream music. The pundits were baffled – the established trope would have been to hunker down with a big name producer for months to buff their rough edges to a luminescent sheen (see Metallica’s Black Album, released the month prior to Nevermind), so why were they going with an indie rock scrub like Albini? Compounding the media’s confusion was the tidbit that Albini had only begrudgingly agreed to do the album, insisting all communication about the session be directly between himself and the band with no label involvement. The kicker: He wanted to be paid a flat fee for his time and not receive royalties for the album, leaving an unfathomable amount of money on the table, because, in his mind, that would be taking money out of the band’s collective pocket for their artistry. “I think paying a royalty to a producer or engineer is ethically indefensible,” he wrote in a lengthy letter to the band, laying out his terms before committing to the album. “The band write the songs. The band play the music. It's the band's fans who buy the records. The band is responsible for whether it's a great record or a horrible record. Royalties belong to the band.”

The next time I encountered Steve’s name was in college in the late 90s. The internet had altered discourse and suddenly content once lost to the sands of time was reemerging online and circulating through the culture. And so it happened that I came across Albini’s scathing screed about the parasitic structure of the music industry The Problem With Music, which helped me to understand the mindset he brought to negotiating the Nirvana session. It was revelatory, digging into the minutiae of the economics of the industry and lambasting the dilettantes that lay in wait, poised to shove their hands into the pockets of any act they saw on the rise. Its critique underscored the realization that had taken root in me since my immersion in the Chicago punk scene, that the DIY and indie underground was not an alternative to corporate music so much as its own parallel world. That the emphasis on community, mutual support, creativity, and independence were not just features of an ecosystem trying to sustain itself with limited resources, but, in fact, a template for how to live an intentional and ethical life.

It makes sense that his business practices were informed by this sense of community because it was the very thing that set him on his path. In his early years in Chicago’s punk scene, Steve struggled to find a studio that was willing to record his music. Studios of the era were wary of punk bands and/or didn’t know how to properly capture their sound, so he took it upon himself to rent a 4-track recorder and some microphones and learn to do it himself. When the word got out that this was a new skill he’d developed, other bands started asking him to record their music. Anyone who has spent time in a burgeoning scene recognizes this pattern. Each person develops some skill or asset that they can lend to the others. Maybe one person works at the copy shop and can print the fliers for free/cheap, one person owns a van and can rent and transport the PA for gigs, one person has a garage or basement where the shows can happen and so on. Before long bands from out of town started booking him as more and more caught wind of his proclivity for making great sounding punk records, which was key at a time when very few engineers knew how to because they simply didn’t know what it was supposed to sound like.

It was a long-ascending path that led him to recording In Utero, and he surely could have followed the map that has played out so many times in independent music: parlaying minor victories in the DIY world into bigger and bigger opportunities, each a rung on a ladder that leads to wealth and prominence. But the words I see coming up again and again in the many remembrances circulating about Steve are not “strategic” or “ambitious,” they are “generous” and “principled.” With the new resources and opportunities opening up to him, Steve reinvested in the music community by building Electrical Audio, a world class recording studio that he made available at what amounted to bargain rates. The impact of that decision is immeasurable. It is no understatement to say that it quickly became a cornerstone of the Chicago music community and a sonic stamp on more records than one could listen to in a lifetime.

His generosity and commitment to being a decent human being didn’t begin and end with the studio or the music scene. In recent decades he and his wife Heather have run a local Letters To Santa initiative, staging an annual 24 hour music and comedy event that raises money to distribute gifts to Chicago’s most under-resourced families. But his altruism didn’t blind him from recognizing his faults. In 2021 he had a public reckoning with how his pursuit of abrasiveness and tendency for shit-stirring had unwittingly contributed to a hateful strain of discourse. “It’s been a process of enlightenment for me to realize and accept that my very status as a white guy in America is the product of institutional prejudices, that I’ve enjoyed the benefits of them, passively and actively,” he told Mel Magazine that year. “And I’m responsible for accepting my role in the patriarchy, and in white supremacy, and in the subjugation and abuse of minorities of all kinds.”

When I first stumbled into punk as a fresh-faced 14 year old in 1992 there was a lot of talk about how it was more than music, that it was a framework for how to carry oneself through the world in an independent and ethical way. Over time I came to realize that the development of this ethos was not something that happened concurrent with punk’s emergence as a music genre, rather it was a seed that was planted and cultivated by the most thoughtful and visionary of its early adopters, Albini among them. They saw a spark of a better world in the scenes they built and structured their entire world around nurturing it and helping it flourish. Part of what is so powerful about the punk ethos is the way that it feels like it taps into something that is timeless and intuitive. As Minutemen put it “our band could be your life.” There was hardly a purer expression of the potential of punk to render the world a better place than how Albini carried himself in life.

I can’t claim to have known Steve well, but he was always just around. I’ve recorded something like nine records at Electrical Audio, and hopefully there will be many more to come. I remember when Pelican made our first recording there in the Spring of 2004, amid the excitement of recording in a “real” studio after a decade of basement studios and home recordings, feeling a rush of anticipation and jitters. Would Steve be there? Will we meet him? What I came to realize and relive over the course of 20 years was that, yes, Steve was pretty much always there, working, repairing things, drinking coffee, watching TV, mastering poker, playing billiards, fielding calls. But when I ran into him that first day I couldn't have known that, so I reverted to blubbering fan mode and began punishing him ad nauseam about that Shellac show in 1998. I told him how it had felt to be in the audience when people started losing their minds, how I’d met my wife there. He was cordial, but seemed distracted and perhaps disinterested. I knew I was making an overeager first impression. I figured he would forget about it as he had much more important things and much more important people to contend with. But I didn’t realize that Steve’s attention was not hierarchical, and that I’d go on to see him generously give his time and focus to so many people for many years to come.

The next day I walked into the studio’s kitchen while our drummer Larry was talking to Steve. By some coincidence he was telling him about the very same show I had talked his ear off about the day prior. In that moment I pictured his life as a revolving door of people telling him variations of the same stories again and again, regurgitating his life back at him in an infinite loop, perhaps even an unconscious inspiration for Didn’t We Deserve a Look at You the Way You Really Are. I was listening and imagining how all these various retellings must wash together into an indistinguishable blur of anonymous faces and life details when Steve cut in, “Yeah, that was a fun show. Trevor got laid, you know.”

Trevor Shelley de Brauw is a punk parent, experimental rock musician, and insufferable bore based in Chicago sometimes known for his work in Pelican, RLYR, Chord, and beyond.

More in Hell Word on artists that left us way too soon:

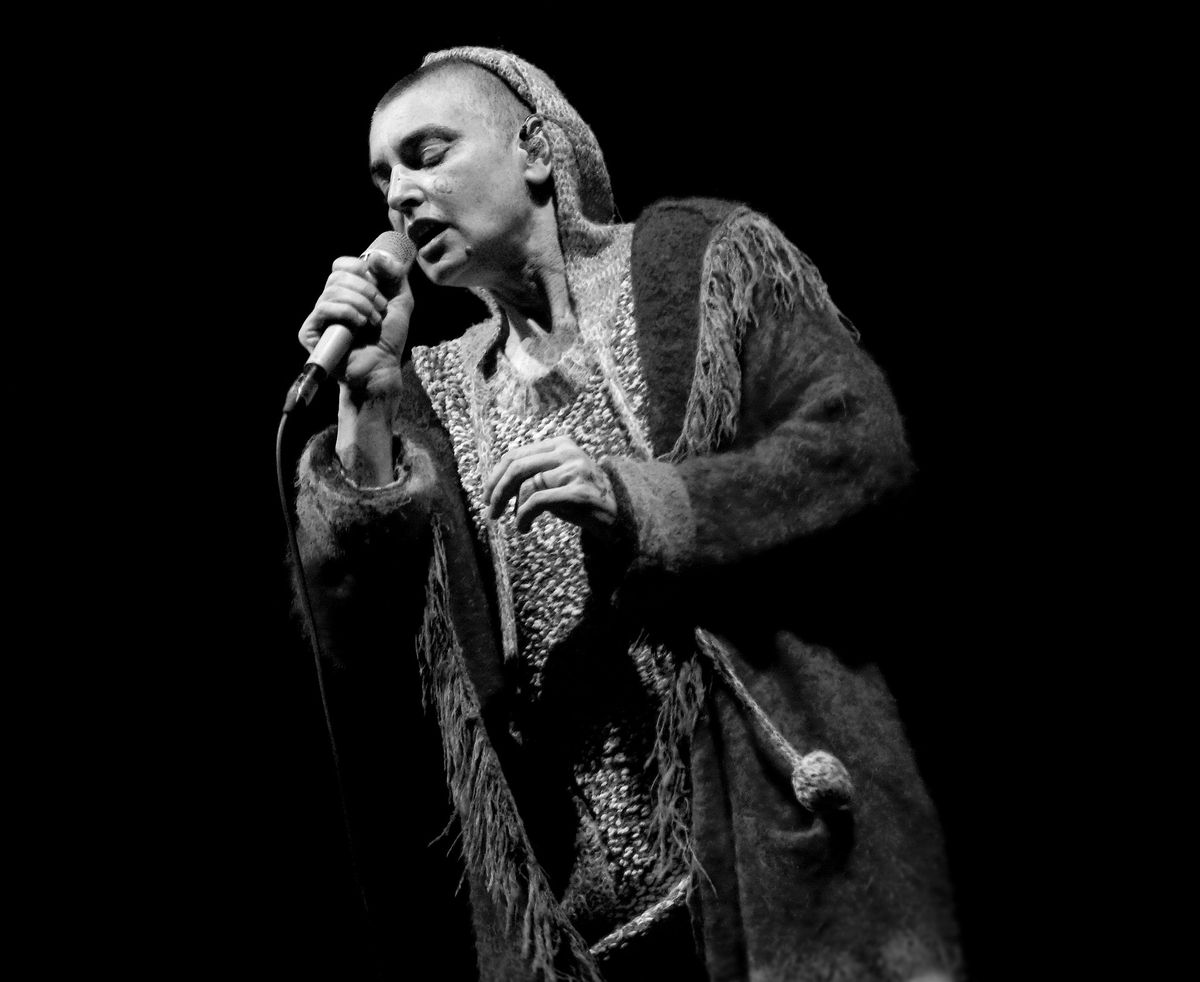

Sinéad O'Connor

Mark Lanegan

Kurt Cobain

Elliott Smith

Jason Molina

David Berman

Rick Froberg

Chris Cornell