He wanted to see his paintings move

The life and art of David Lynch

I gotta stop smoking one of these days.

Corey Atad writes today on the life and art of David Lynch. Most recently for Hell World he wrote about the 1995 David Fincher film Se7en, the fraught decision to have children or not in times like these, and whether the world is still worth fighting for.

More from me about another loss below.

The great artist

by Corey Atad

Filmmaker is too narrow a description for David Lynch, who directed movies, but whose work even in cinema broke the bounds of the medium. He was, in fact, an artist in the real sense. A multidisciplinary conjuror of singular expression. The Art Life is what Lynch dedicated himself to, his work pouring out in all directions, using whatever media he could get his hands on. Lynch had wanted to be a painter, and early on was influenced by the European avant-garde, pursuing the discipline at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art in Philadelphia alongside his friend and future production designer Jack Fisk. The story goes that he made his first short film, 1967’s Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times), because he wanted to see his paintings move. It’s a scatological film, an animated painting of a group of figures, their insides visible, fluid filling up and spewing out of their mouths. One minute of footage, looped for a four-minute running time, eerie and ugly and beautiful to look at, and oh so Lynchian.

More shorts would come, despite Lynch’s wariness of film, its difficulty and expense. In 1968, using money from a failed commission, he made The Alphabet, further melding the tools of animation and live-action photography. In 1970, with a grant from the American Film Institute, where he would eventually study, he made the 33-minute The Grandmother, about a boy growing up in squalor and abuse, who literally spills his seed and grows a grandmother out of a giant plant on his bed. The startling thing about watching Lynch’s early shorts is witnessing his singularity arrive fully formed. Each represents an expansion of his toolkit, but his expression is clear at the outset. This is perhaps why Lynch had the remarkable career he did, struggling always to produce his films, but finding backing nonetheless, his artistic genius so plain to see it inspired good will at times even from the most heartless studio executives.

Lynch never stopped painting. Or sculpting. Or directing. Or making music. Indeed, he made himself into a kind of artwork, crafting the image of a true eccentric. The hair, the suits, the cigarettes, the way he spoke. He had the manner of a huckster, and the sensibility of one, too. The great American artist and salesman, gleefully mum on the meaning of his work, but always ready to hawk it. He had as much William Castle in him as Stan Brakhage. Not to be confused for a sellout, Lynch embodied the impulse of creation embedded in the entrepreneurial American spirit. When he directed commercials, they were unmistakably his, no different from any of his other art. Whatever avenue presented itself was an opportunity for boundless creativity. He was mercenary in the most wonderful way. Cinema became his great medium only because it combined all of the others.

It may sound hyperbolic, but it would be hardly out of place to claim Lynch was the great artist of the last half-century or more. I’d be pressed to name more than a handful of others about whom the same could plausibly be said. Eraserhead, that midnight movie sensation, the product of years of labour by Lynch and his collaborators, stands as a turning point in the history of cinema and art. It’s not like surrealism was anything new in 1977, but in the story of a man suffering the torment of raising a deformed baby, Lynch created something like a whole universe. How many filmmakers are recognizable just by their sound design? He pinpointed something real and upsetting about the human experience. Taboo, even. What stuck out then was the nightmarish quality of his art, undercurrents of ugliness and evil pervading all in dreamlike horror. What sticks out now is its earnestness.

More than most other filmmakers, Lynch’s artistic practice was one of feeling first. He was famously a devotee of Transcendental Meditation, which he discovered in the early ‘70s, and which became a lifelong pursuit. He tells the story of his sister recommending it in his 2006 book Catching the Big Fish. In that book, Lynch explains how his meditation practice became key to his art life, lifting from his mind any fears, making room for a totally freeform imaginative exploration. The dread and darkness in his work, all those fears expressed of society, machinery, people, were but one facet of a grander, more endearing vision of humanity. There is no good without evil in Lynch’s world, and the full expression of one demands the other.

Learning the sad news of Lynch’s death at 78, I spent much of my day in a stupor, though I knew I would find solace in watching some of his films. I put on The Grandmother, and Eraserhead and Mulholland Drive. Not much needs to be said about any of those masterpieces but to recommend watching or rewatching them yourself. I also put on The Elephant Man, which might be among the most heartfelt films ever made, right alongside Lynch’s later film The Straight Story. Scene after scene in The Elephant Man feels purpose built to make you cry. It makes me cry. And I cried. It’s a film about the cruelty of the world, and about the meaning of dignity. “It’s finished,” says John Merrick, after signing his name to a model cathedral he’s constructed from the sight of a spire out his window, using his imagination to fill out the rest. He then prepares his bed to lie down and pass away. His life in his hands, his expression fulfilled, and his suffering finally ready to be alleviated.

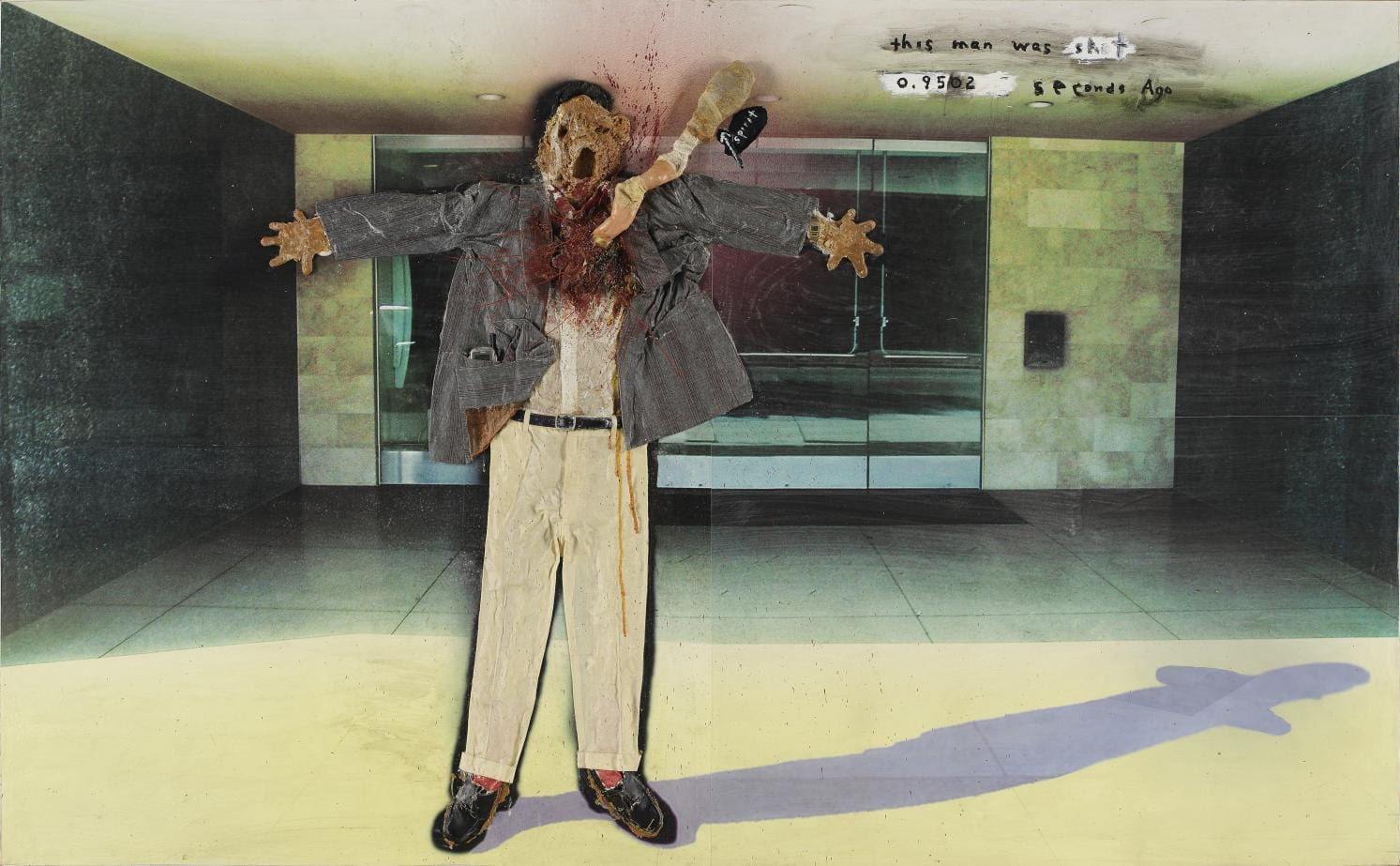

When I think about Lynch, I think a lot about death. He was consumed by it himself, in a fashion superficially described as morbid. Look no further than his multimedia painting This Man Was Shot 0.9502 Seconds Ago from 2004, an image of a terrifying figure, his chest exploding as his spirit physically departs his body. It’s violence and death, captured at the moment of impact, bracing in its immediacy and haunting in its gross and uncanny cartoonishness.

In 2017, Lynch and collaborator Mark Frost gifted us Twin Peaks: The Return, which even at the time felt elegiac. There were the actors unable to come back because they had died. And there were those who died in between the series’ production and its premiere. Since then, others have died, too. And now Lynch. “You know about death, that it's just a change, not an end,” says Catherine E. Coulson’s Log Lady in The Return. Hooked up to oxygen and looking frail from cancer, it was Coulson’s last collaboration with Lynch after the two first met in 1971 and worked together on the 1974 short The Amputee. She died in 2015, nearly two years before The Return aired. Violence is violence in Lynch’s world, but not death. Death is but a change, another step on the path of The Art Life. Coulson lives forever now, and so does Lynch.

In 2020, during the pandemic, the housebound Lynch gifted the public with his daily Los Angeles weather reports. His last one, on December 16, 2022, predicted partly cloudy skies. “Everyone, have a great day,” he said with his trademark optimism. It was just days after his longtime collaborator, composer Angelo Badalamenti had died, and only months after their fellow collaborator, the singer Julee Cruise, had also died. “Today I was thinking about the song The World Spins,” he said in the weather report, recalling that it was their favorite song they’d made together. He offered no further explanation.

Corey Atad is a freelancer writer living in Toronto

There are way too many to choose from but this story about Lynch as told by Peter Wolf of the J. Geils Band always delights me every time I come across it.

I never finished high school and spent a lot of my time hitchhiking around the country. I would show up at different colleges and universities pretending I was an art student. During a hitchhiking visit I dropped off some paintings at the Museum School, which was affiliated with Tufts, and they accepted me.

The first day I arrived back in Boston, I stayed at the Y.M.C.A. for one night, because that's the most I could afford. The next night I spent sleeping on the Charles River. The third day, since it was raining, I knew I needed to find a place quick. I spent a good deal of time at the school’s hallway bulletin board looking over the “roommates wanted” list, when a voice behind me asked if I was looking to find a roommate. That person turned out to be David Lynch. So that night I moved into his one-bedroom apartment on Hemenway Street.

It was a small apartment with a bunk bed. We were pretty much like “The Odd Couple.” I was a heavy smoker and enjoyed a drink or two, or sometimes even three. I was pretty much a sloppy person, and I believe David liked things a bit more orderly. (One “Lynchian” moment I remember was when David realized there was a cockroach on his toothbrush while he was brushing his teeth.)

But what bothered David the most was my delinquent rent payments. It was a great surprise to me one day, when I came back to the apartment, to find that the lock had been changed. But a changed lock doesn’t stop a Bronx street kid. By using the fire escape, I unlocked the windows and took out all of my belongings.

About 20 years later, David and I were having lunch in Los Angeles. It was just after he made “Blue Velvet.” We had a very enjoyable afternoon reminiscing, but he also politely reminded me that I still owed him $43.20 for back rent.

David Lynch – just like everyone always says – was a true Boston icon.

I have taken this piece out from behind the paywall. You should read it if you didn't get a chance to. It would be nice to still pay for it if you can though.

Read Jonathan Katz here on the alleged ceasefire.

Finally, even if the deal is ratified, Israel’s track record of honoring ceasefire agreements is not good—a fact underscored by its relentless assault across Palestinian lands even as its negotiators have agreed in principle to ceasefire terms. Last night alone, the Israelis killed at least 53 people, most of them women and children, in a single strike in Gaza City, while simultaneously carrying out deadly airstrikes on the occupied West Bank. The Hamas-run Gaza health ministry says that 81 people were killed and 188 wounded over the last twenty-four hours, Haaretz reported. (Hamas has also historically broken ceasefires, though they hardly seem to be in a position to in the near term.) Israel will still control the sea and skies. And under the draft agreement, their ground forces will remain inside the borders of Gaza, likely including the so-called Netzarim Corridor — a line of occupation bisecting the strip from which they stage attacks and control the flow of people between the north and south. At the slightest provocation, or even without one, it can all start up again.

I certainly hope it is real but I will believe it when I see it. I don't currently believe I will.

I am sitting in a waiting room right now none of us ever want to be inside of crying about an old friend I'm not entirely sure is even dead yet. The telephone game both figurative and literal going on among friends. I called him to no answer hoping this was all a misunderstanding and then texted to say "you alright ?" to no response and then felt the curious mix of shame and devastation that I had just texted a dead man.

I guess I was expecting some kind of miracle.

I noticed the last time we had texted was two years ago when he sent "Nollaig shona duit" and I said "Happy Christmas to you too old buddy."

He was from Ireland but had been here for twenty five years or more working in the hospitality business in the Boston area and he hired me for a restaurant job I would have for many years that changed my life in both good ways and bad. I had some of the best and absolutely most disgusting nights of my life with this man. Sitting in the closed down restaurant all night chain smoking under the heating vents. Going across the city at 4 in the morning to get another bag that neither of us really wanted and certainly did not need. I cannot believe we lived through some of that shit and now I guess one of us did not.

He was sober for many years after we no longer worked together and I was very proud of him for that. While sober he was one of the more charming – and fitting his profession – hospitable people I knew. He was always sort of my boss in the way that someone who was once your boss and is a bit older is always your boss. He was proud of me too for my writing accomplishments while endearingly not ever having any clue about how online media or social media specifically – which he was always pestering me for help with at every new restaurant he was running – worked.

He lived around the corner from us in Watertown and would have Michelle and I over for the most lovely dinners. He knew so much about wine. He'd delight in pouring us important sounding bottles and not have any for himself during the good years there. I'm not going to sugarcoat it he struggled very badly with substance abuse. Oftentimes you probably wouldn't want to be around him unless you were that drunk too or that coked out of your mind and maybe not even then but that is how that all goes. A nice person can become an unbearable one so quickly. I have so many friends like that. Maybe that's me too. I don't think so but I wouldn't know would I? That's the other version of me and we are at odds with one another.

It all feels even stranger because just before I heard that my friend may or may not have passed I had been having a little cry about David Lynch and then my own David was either dead or was not. Restaurant families like the one we were a part of are a fractured fragile thing and I don't know if I know anyone who would know right now. My one friend said their one co-worker said it happened this morning. I hope it's not true. It would be awkward if he has to read this and be like what the hell man? I hope he still can.

--

I wrote that yesterday and now I know he won't. I posted the news to Facebook and everyone is saying how much he made them care about the fine details of working in a restaurant. How he made them more of a professional. He did that for me too. Yes restaurant labor is terrible in many ways but hospitality? That's something else. That's something to take pride in. That's humanity.