Everywhere is the gallows now

We went through the same level of rigor that we've done for years and we took a strike

I have forgotten 9/11. Literally I mean. I remember waking up in my yellow bedroom in my shitty seven loser flophouse in Allston with the brown standing water in the bathtub and the maggots in the pantry and the empty pizza box ashtrays everywhere and watching it on our fucked up little TV like everyone else did that morning. I remember walking in a sort of stupor with one or two of my roommates across the bridge to get coffee on a bright and clear morning and then… it just turns off there like a blackout. Were the streets quiet and empty or am I retroactively imagining that? I have no idea what we did next or if we did anything at all. What were the birds doing that morning? A better writer would’ve made a point of noticing what the birds were up to and I apologize for that.

“You woke me up to tell me I should come downstairs,” my friend just told me when I asked. “I thought you were waking me up because I was late for work. We all huddled around that shitty TV watching the footage before returning to our bedrooms to try and get online. All the phones were down. They would either ring forever or give a busy signal. We used AIM to try to get in touch with our friends in NYC. At some point we walked to Herrell’s…We tried to tell jokes because we didn't know how to process anything. The streets were pretty deserted…I don't think we went out that night. I think we just went back and read the internet and wrote long emails.”

Not much different than today I suppose. The last part anyway.

Michelle just told me about waking up and driving into school at UMASS Boston and listening to Stern on the way in and seeing the sky pregnant with aircraft circling and circling nearby Logan airport just across the water there frantically waiting their turn to land and I thought that was a much more symbolically rich tableau if you were trying to be a writer about the whole thing.

“I saw the towers on fire as the B train was going over the bridge,” another friend just told me. “Everyone on the train had been underground without service and then just as soon as we could register that both towers were smoking we were plunged underground again, having learned nothing.”

That train detail. Like coming up for a gasp of utterly confusing oxygen only to go right back under.

But for me it’s just… blank. I remember a vague feeling of dread about what was about to come next as if some kind of total war was imminent I think or maybe I’m also inserting that in after the fact. That came true in a way but not in the way I thought it was going to.

Don’t do a lot of cocaine in your twenties I guess is the lesson here.

If you appreciate what you read here please subscribe. Thank you very much for reading either way. In fact if you subscribe to the full yearly price of $69 I will send you a copy of one of my books of your choosing. Let me know!

Speaking of shitty apartments every time I see this post the lobe of my brain that tries to make order of the universe keeps going come on man that can’t be real and then I think about any slumlord I ever had and it becomes very believable.

That doesn’t really have anything to do with 9/11 I suppose. Today’s main piece doesn’t either it’s a report by Bill Shaner from a prison abolition protest which you can and should read below or jump straight to here if you want to skip me not-remembering 9/11 very well for a while first.

This other piece is about 9/11 though. Most of you probably read it by now but in case you haven’t or if you want to read it again like the 9/11 version of watching It’s A Wonderful Life here you go.

Bill Moro remembers 9/11 fondly.

He’d gotten up early that morning to go to work at the paper mill like any other day. Tucked into the southwest corner of Massachusetts, not far from the New York and Connecticut borders, the area around Great Barrington, where Bill has lived his entire 67 years on earth, was once one of the centers of paper production in the country but not so much anymore due to they closed all the plants. Bill’s plant, now known as Onyx Specialty Papers, the last mill in the area, sits on the Housatonic River, which travels 150 miles south from there and winds its way down into the Long Island Sound. If he’d picked up a copy of the Berkshire Eagle that morning Bill would’ve seen headlines that didn’t seem all that out of the ordinary. Pittsfield’s Postmaster transferred, read one. Experts say Mideast talks already in doubt another.

And then it was 9/11.

“I was at work when it happened,” Bill said. “Of course we didn’t have a television there, but we had a radio and a newsflash came across the radio. So of course everything was dead silence.”

Bill and his co-workers finished out the day, and not knowing what else to do he said fuck it, let’s go bowling, and man is he glad he did because it was the best game of his life. He’d never bowled so well in decades of trying. He’d never bowl so well again. Amidst the chaos and fear and uncertainty of the world changing in ways neither he nor the rest of us yet understood, Bill Moro went and bowled a perfect damn game on 9/11.

I’ve been thinking all morning that one of the most lingering and troubling remnants of 9/11 is that many of us still to this day think of it chiefly as a personal and insulting affront that violence could be delivered to us the Americans to whom violence is not supposed to be delivered. We’re supposed to be on the other end of the bargain. And then of course we were for the next twenty years.

The New York Times has a great video investigation of one last drone strike for the road on our way out the door of Afghanistan.

“While the U.S. military said the drone strike might have killed three civilians, Times reporting shows that it killed 10, including seven children, in a dense residential block,” they reported.

“Sad that evidence points to the final act of the war being the U.S. killing civilians and likely lying about a car having an IED in it,” Steve Beynon of Military.com wrote on Twitter sharing the piece.

“We’ll see about the ‘final act’ part,” Wesley Morgan, author of The Hardest Place: The American Military Adrift in Afghanistan’s Pech Valley replied. “But yes, both sad and par for the course. General Milley summed it up better than he probably meant to when he said ‘We went through the same level of rigor that we've done for years and we took a strike.’”

You’ve probably seen this New Yorker article about the women of rural Afghanistan being shared by now but you should read it if you haven’t.

“They would drop leaflets saying, ‘Stay in your homes! Save yourselves!’” Shakira recalled. In a war waged in mud-walled warrens teeming with life, however, nowhere was truly safe, and an extraordinary number of civilians died. Sometimes, such casualties sparked widespread condemnation, as when a nato rocket struck a crowd of villagers in Sangin in 2010, killing fifty-two. But the vast majority of incidents involved one or two deaths—anonymous lives that were never reported on, never recorded by official organizations, and therefore never counted as part of the war’s civilian toll.

In this way, Shakira’s tragedies mounted. There was Muhammad, a fifteen-year-old cousin: he was killed by a buzzbuzzak, a drone, while riding his motorcycle through the village with a friend. “That sound was everywhere,” Shakira recalled. “When we heard it, the children would start to cry, and I could not console them.”

…

Entire branches of Shakira’s family tree, from the uncles who used to tell her stories to the cousins who played with her in the caves, vanished. In all, she lost sixteen family members. I wondered if it was the same for other families in Pan Killay. I sampled a dozen households at random in the village, and made similar inquiries in other villages, to insure that Pan Killay was no outlier. For each family, I documented the names of the dead, cross-checking cases with death certificates and eyewitness testimony. On average, I found, each family lost ten to twelve civilians in what locals call the American War.

That ellipses I inserted there skips over seven human being’s deaths and I’m sorry about that.

I was awoken in the middle of the night last night by what I thought at first was someone moaning in the street then I thought in the way in which you can’t ever think straight when you’ve just woken up that it was someone taunting me specifically outside my window and then I went outside and realized it was people at a party singing Man! I Feel Like a Woman by Shania Twain very loudly and poorly and drunkenly and I assumed it was my next door neighbors and at that moment I wanted to go over and pummel them but it wasn’t even them doing the singing they were just in bed too probably being similarly annoyed. Instead it was some other unrelated group all the way somewhere else down the street. But in that moment I wanted to act so rashly. I wanted someone anyone to know how fucking pissed off I was. I wanted my dumb sleepy errant revenge.

Instead of that what I did was I took a muscle relaxer and went back to bed to dream about a man with no eyes standing over me that wouldn’t let me scream out in terror no matter how much I needed to.

Sometimes I worry that it might seem like I don’t take 9/11 seriously but I very much do I cannot overstate the horror it must have been but at the same time I think maybe the reason it has become such a fertile ground for half-joking conspiracies and memes and so on is because of how truly and confoundingly absurd and idiotic and brutish our reaction to it as a country was after the fact. Gallows humor sometimes feels like the only response to such a nightmare and then we went and built a whole massive globe-spanning gallows for millions of people to stand on for decades waiting for the fall. Everywhere is the gallows now whether it’s because of our imperialistic wars or a deadly still ongoing pandemic.

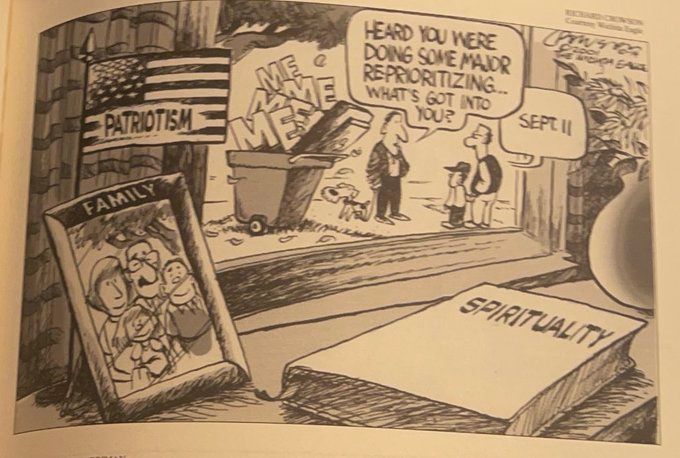

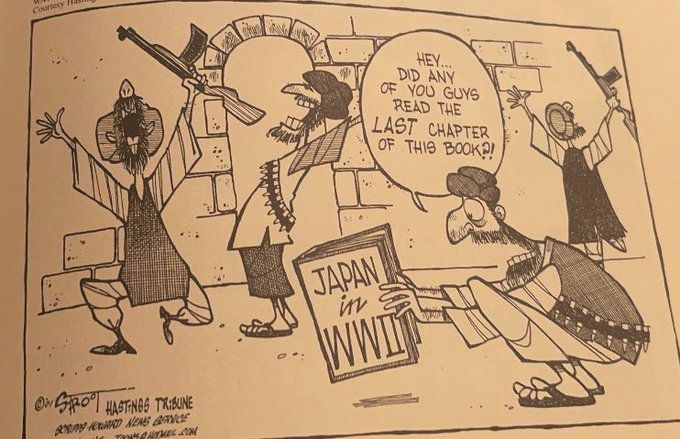

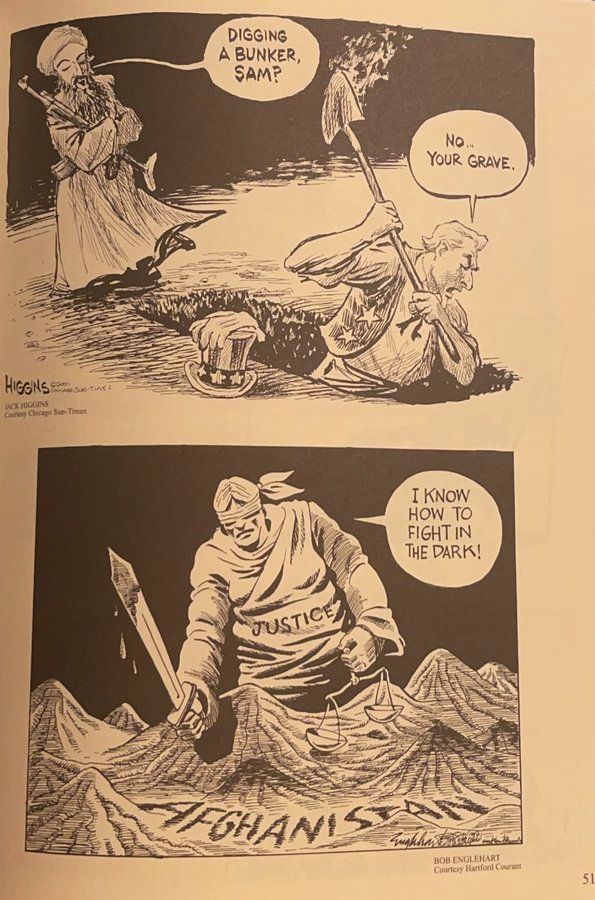

Check out this thread of political cartoons from shortly after 9/11 if you want to remember what the prevailing consensus was like back then.

It’s impossible not to compare 9/11 to the situation we’re currently in with Covid right now. Here look at this: This week “the daily average of deaths rose to 1,579, up 28% from two weeks ago and the most since March 9... The seven-day average of people hospitalized was 100,610, up 1% from two weeks ago and the 14th-straight day that it has topped the 100,000 mark.”

“The responses to 9/11 and the coronavirus pandemic make for an instructive comparison,” Ryan Cooper wrote in The Week today. He compares 9/11 to the death toll of other much more bloodier days in history throughout the world before rounding back to Covid.

Most tellingly of all, at time of writing, the official toll of Americans killed by COVID-19 stood at over 656,000. Given that a study published in May estimated that the true toll was over 905,000 (thanks to many COVID deaths being missed), it is likely that COVID has claimed the lives of something like 1.1 million Americans so far, with no sign we are anywhere close to the end yet. That means the pandemic has killed somewhere between 0.2 and 0.3 percent of the American population — roughly between a 190 and 310 times greater share of the population as died on 9/11.

A recent Twitter thread of post-9/11 political cartoons is a good representation of the deranged mindset that took hold of American politics after the attacks. It was supposedly an event that “changed everything,” and it was worth spending any amount of money to prevent from happening again. Yet when that same number of Americans are dying every two days from an easily preventable illness, conservatives not only don't care, they react with furious outrage at efforts to halt it. When President Biden proposed a vaccine mandate for businesses with more than 100 employees, conservatives threw an instant tantrum, including at least one veiled threat of violent insurrection from a high-profile GOP politician.

I tried my hand at weighing the costs of both tragedies at once back in February of this year in this paid Hell World.

This coming Sunday is the anniversary of the first American death from the pandemic. The first of 500,000. How do you feel about that number? It just kind of sits there in its grandiose heft for me. Like if you saw a dinosaur come to life emerging over a hill into a clearing its immense stupid body unfurling in front of you you wouldn’t go oh look at its little nose you’d behold it all in its uncanny size at once and be struck dumb. I can’t personally make much sense out of it. 500,000 dead now in under a year. What is that? It makes my brain feel slow and dry like when you’re struggling with an especially dense philosophical text or something or like when your fight or flight reflexes kick in and you instinctively know that you’re somewhere you shouldn’t be. It’s when you go down in the basement. It’s an ejector button for comprehension. You cannot hold the deaths of 500,000 individuals from a pandemic in one country in your brain all at once it overloads the system. It’s Lovecraftian and just as if not more racist. …

One thing I was always suspicious of regarding the counting of the dead was the way people started using 9/11 as a point of comparison. I suppose at first it made sense because that was the most recent example of death on a massive scale in one fell swoop in America from the same singular event but there was always something so absurdly comical about it as if “One (1) 9/11” was a standard unit of measurement recognized in the death tabulating community. Besides that it completely misses the “meaning of 9/11” in that it is specifically a day most of us vividly remember in detail and can very much comprehend and all of these deaths these 500,000 friends are amorphous and impossible to corral into a moment in time. 9/11’s novelty was what built its meaning.

And then more on the shittiness of my memory I suppose.

I have a very hard time Quantum Leaping into moments of my own life and I’m not sure if that’s something unique to my particular frame of consciousness or if it’s more universal. I can remember the contours of my surroundings and what things looked like — for example I remember very well the morning of 9/11 and a dazed sort of aimless walk with my roomates to the coffee shop (RIP Herrell’s in Allston baby) — but I have no fucking idea what the specific thoughts I was experiencing at the time were aside from nebulous notions of anxiety. Are people able to do that? Can you pick a moment in time out of your life and remember what you were thinking in complete sentences?

I am not sure either if this is something I was still able to do before social media before we offloaded our memory files to elsewhere but the backwards expanse of my life was much shorter then so maybe.

I don’t remember.

I am fairly certain I was looking forward to a long and normal life at that point. A certain moment in time arrives — and we don’t know that it’s happening as it’s happening — when your thoughts stop being about the life you are expecting you are going to have and they become about the one you have now and the one you had before and will never have again.

When I try to remember 9/11 or anything else momentous there’s a camera hovering over my shoulder watching me watch what was happening elsewhere on a television. Just now I had this shudder of another memory of watching some bombing or other…(Kosovo? There have been so many in my life who can keep track) on a low definition TV in its sickeningly green night vision filter. People were very excited about that at the time. I watched that in a room across the hall from my dorm room I think. I remember we watched the Patriots lose to the Packers in the Super Bowl on that same TV. Both memories are flattened together into just some thing that happened somewhere while I was busy worrying about the next next five and ten and twenty years of my life all of which have already passed me by at this point. How amazingly lucky that there’s very little remarkable to ever have had seared into my memory in all that time. May we all lead such unhistoric lives.

Wait I don’t know how this is possible but I just had another memory remembered for me by another friend. Apparently my old band played at O’Briens in Allston the night before 9/11. No one was there he said except for maybe our one friend at the time who went on to become more famous and successful than everyone else we knew back then. A week before that we had flown to Los Angeles to make a record that we were sure was going to be our big break he said. I remember doing that of course but I had no idea it was so close to 9/11.

“I’ve always thought of TGN and 9/11 together in that the band started in 2001 and we went to LA with so much hope the week before — the engineer at that studio said ‘oh yeah you’ll definitely get signed from this’ — only to come back to the world and music industry having completely changed.”

Then he said the flight we took was American Airlines Boston to LA. Lol what the fuck? How do I not remember that? Well there you go. Everything that has ever happened is about me after all just as I’ve always suspected I just couldn’t remember why.

No New Women’s Prisons

by Bill Shaner

Today Bill Shaner reports on an anti-incarceration march in Massachusetts organized by Families for Justice as Healing among others. In April he reported for Hell World on the (still ongoing) strike by nurses at Saint Vincent Medical Center. He writes the newsletter Worcester Sucks and I Love It.

If you can look past the inherent cruelty it’s a simple question of math.

A woman in prison costs the state about $100,000 a year. There are, give or take, 135 prisoners in MCI-Framingham, the only state-level women’s prison in Massachusetts. So back of the napkin we’re at about $13.5 million a year.

The state is considering spending $50 million to construct a new prison for these women, where they will continue to cost the state $13.5 million a year, only somewhere else. Somewhere cosmetically different.

What’s the point?

That’s the essential question asked by a coalition of abolitionist and prison reform groups which yesterday embarked on a statewide march in support of proposed legislation to put a five-year ban on all new prison construction, effectively spiking the construction of a replacement for MCI-Framingham.

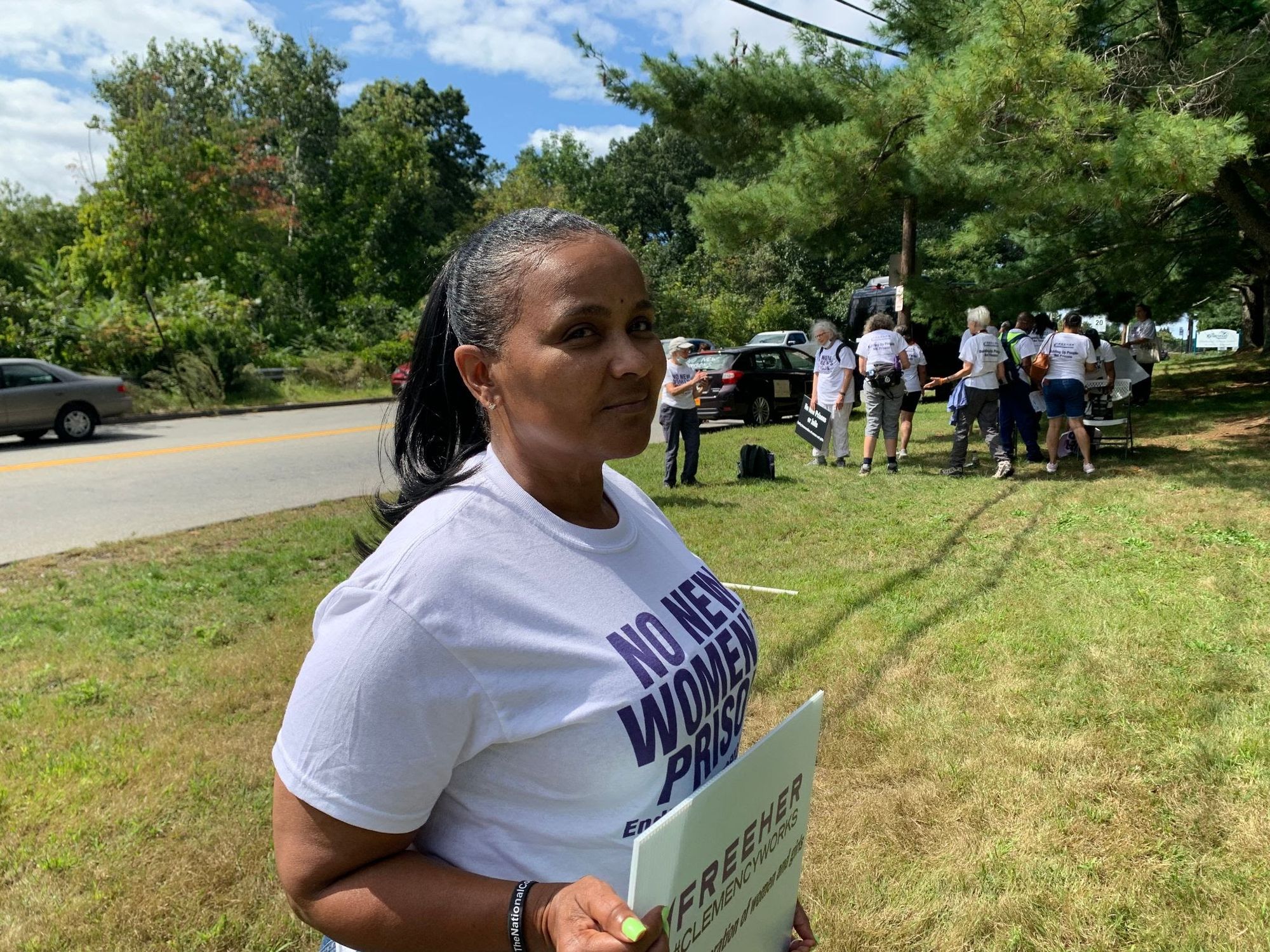

They began yesterday morning in Worcester with a rally outside the courthouse. Then they embarked on a six-mile march to the Worcester House of Corrections, a county jail tucked unassumingly in a woodsy suburb just outside city limits. I caught up with the group halfway through the march and found them stopped on a patch of roadside grass for a break. Several dozen demonstrators held signs and waved to a steady line of passing drivers in mid-day traffic. They all wore white shirts sporting a message in bolded all-caps and purple font reading “No New Women’s Prisons: Ending Incarceration of Women and Girls.” Songs of freedom and abolition and also Walk on The Wild Side at one point, because why not, blared from speakers in the back of a pickup truck.

The march is the brainchild of Andrea James, a formerly incarcerated woman and the executive director of the National Council for Incarcerated Women and Girls, as well as the local organization Families for Justice as Healing. Since her release from prison in 2011, James has made the decarceration of women her life’s work.

“We’re here to say that the last thing we need in Massachusetts is another women’s prison. We have one of the lowest incarcerated populations in the country,” James told me during one of the few moments she could step away from organizing the march. “We have 135 women in our state prison. And we should be creating what ‘different’ looks like.”

Indeed Massachusetts’ female incarceration rate is well below a national standard that is, by measure of the rest of the world, egregious. A 2018 study by the Prison Policy Initiative found that the U.S. accounts for 30 percent of all the world’s incarcerated women, despite having just 4 percent of the world’s female population. The female incarceration rate in the U.S. as a whole is 133 women per 100,000, according to the study. It’s the highest rate in the world, followed by Thailand, El Salvador, then Russia. By state Oklahoma has the country’s highest rate at 281 per 100,000. Twenty six states have a higher female incarceration rate than any country in the world. Massachusetts’ on the other hand is just 40, higher only than nearby Rhode Island’s rate of 29.

Massachusetts’ relatively low population of incarcerated women is exactly why James and company feel it’s so important that the state not invest any more money into new prisons.

“We’re not a California. We don't have 1,000 women just in one prison,” she said. “Total, if you throw in the county jail sisters, we've probably got 500 women in a cage somewhere. If we can't figure out what different looks like and be a model for the rest of the country, with apparently what is millions and millions of dollars that they have to spend on this, then shame on us. And that’s why we’re here.”

As I spoke to James some passing drivers honked and cheered for the demonstrators. The driver of one car honked more emphatically and for longer than the others, so much so that I drifted away from the conversation to take a look. There was a young white woman in the passenger seat, visibly in the middle of a red-in-the-face hard cry. She looked at the demonstrators and nodded her head slowly in approval, tears streaming down her face. Perhaps, I thought, she was on her way to the Worcester House of Corrections, just down the street, to pay someone she loves a visit. Someone who’s been there too long. Someone who could have benefited more from a different approach to justice and restoration.

It was the start of the “The Long March for No New Prisons and Jails in Massachusetts,” a weekend-long event in opposition to the construction of a new women’s prison. Today demonstrators held a press conference outside MCI-Framingham, the only state prison for women in Massachusetts, and marched from the prison to Wellesley Town Hall. Tomorrow, the march picks back up on the Cambridge Common at 10 a.m., and at noon they’ll set off to the Suffolk County Jail for a 4 p.m. standout in memory of Ayesha Johnson and Rashonn Wilson, who both died in custody at the South Bay Jail. On Monday, the demonstration culminates in a march from the Suffolk County Jail to the Massachusetts State House for an 11:30 a.m. rally in support of the legislative push for a moratorium on new prison construction.

The legislation is called “An Act Establishing A Jail and Prison Construction Moratorium” and it was filed in late March. If passed, the measure would prohibit the creation of any new prison, any expansion of capacity in existing prisons, or the reviving of any dormant facility. Basically, it would bar any sort of spending on anything besides the maintenance of existing prisons for five years.

For the past several years, state officials have targeted MCI-Framingham for demolition, saying it’s old, dilapidated and beyond saving. They want to rip it down and build a new shiny prison, to the tune of about $50 million, in Norfolk, on the footprint of a former men’s prison called Bay State Correctional Center. Right now, the center is used only as office space for Department of Corrections employees.

In 2019, the state started seeking bids for the design of a new women’s prison with the goal of moving prisoners by 2024. An inspection from that year found dozens of violations at the Framingham facility, including shoddy plumbing, dirty kitchens, moldy and rusted showers, rodent droppings and a lack of toilets, among other things. The prison, opened in 1877, has fallen into a state of obvious disrepair, or such was the takeaway of the Department of Public Health inspection. The state tasked potential contractors with a design that sets “a higher standard for women’s correctional centers.”

This April the DOC chose the architectural firm HDR for the project after a three hour presentation followed by brief public comment in which abolitionist activists were roundly ignored. HDR is a national architectural firm with a long track record of designing prisons and courthouses, and promised a prison which offers “trauma-informed care” and “an environment with natural light, access to views of nature, normalized furnishings and finishes, in addition to soothing colors [that] can help reduce anxiety, fear, anger, and depression,” according to its proposal.

All of the people I spoke to at the march yesterday scoffed at the idea a prison could adequately provide “trauma-informed care.” When I asked James about the idea, she launched into a heated rant. The culture of incarceration—from the trappings of the system itself to the attitudes of the guards to the simple psychological diminishment of confinement—do not change with a new building, she said.

“We know there’s no such thing as a ‘trauma-informed prison,’” she said. “They want to paint the walls pink. They want to put in gardens. They want to increase the time that children spend in prison with their mothers, and we're like, ‘Hell no.’ First of all you're talking about our children. You're talking about the same families from the same communities. You're not talking about shifting and looking for people from Newton to lock up. And so you're not going to build a new prison for our daughters and our granddaughters to land in. And you're certainly not going to indoctrinate our children by allowing them to spend more time in a prison.”

When James says “our,” she means Roxbury. It’s where she’s from, and it’s where most of the activists at the march were from. She called it the most heavily incarcerated corridor in the state, so much so that parts of it made it onto the landmark 2012 “Million Dollar Blocks” study of poor neighborhoods ravaged by the criminal justice system and constant cyclical incarceration. What Roxbury and neighborhoods like it need is fewer police, less criminalization, and more resources, she said.

“We know that it’s been a level of austerity in investment in our communities. And what they've done instead is invest in police and in prisons,” she said.

Stacey Borden, another demonstrator, aims to do the opposite. She launched New Beginnings Reentry Services, a Dorchester-based home for women reintegrating into society after prison time. Borden herself spent the better part of 30 years in MCI-Framingham and is now a licensed clinician and trauma specialist.

“I was in and out of Framingham for years and I owe it to the sisters back there to bring them home,” she said.

Via partnerships with local non-profits, colleges, and the public schools, New Beginnings aims to offer a way out of the criminal justice system and, ultimately, a model for how to rehabilitate people without it.

“We want to build the women up to go back into the community and bring the resources that our community needs and deserves. Because we know we're most directly impacted. That's it.”

James and Borden both approach the issue from an abolitionist framework. In their ideal world the prison as we know it does not exist, replaced by a more humane, just and effective system. And they work in tandem.

“I met [James] back in 2012 and I said ‘you get ‘em out and I'll keep ‘em out,’” said Borden. “It’s my job to keep them out.”

Both talked at length about how $50 million could be better spent than on a prison building that simply replaces an old one.

“That $50 million should be going to those community-based programs that are directly impacted,” said Borden. “And we could do a lot better to serve women, allowing them to heal outside of a prison and inside a community.”

The perception that prisons do not—and categorically cannot—rehabilitate inmates for a healthy life on the outside was at the forefront of the minds of everyone I talked to. But perhaps none more so than Danielle Metz, a New Orleans resident who flew up to accompany Jones in the demonstration despite a home left in shambles by Hurricane Ida. Metz, who spoke with a thick bayou drawl, spent most of her adult life in prison, sentenced to three life sentences on drug charges when she was 26. Through the advocacy of James and others, she received clemency from the Obama administration in 2016. Now, a free woman, she lends herself to the cause when she can.

“You know, I'm free but I'm not free until they're all free,” she said. “Because you sort of have survivor's remorse.”

Like James and Borden, Metz scoffed at the idea a prison could be designed to be more humane and more sensitive to trauma.

“Nothing you can put inside of a prison to me can be ‘trauma informed,’” she said. “It’s almost like you have PTSD when you come home because you've been through a traumatic experience in prison. So you can’t build that in a prison. Why can’t we build that in the community?”

As of yet, the bill to ban new prison construction hasn’t really gone anywhere. Sponsored principally by Northampton State Sen. Joanne Crawford and Roxbury State Rep. Chynah Tyler, it’s been referred to a subcommittee and was scheduled for a hearing in July. But that’s it. There’s been no significant action to bring it toward a vote. Still, the bill enjoys a fair amount of support: Twenty-eight state reps and 22 state senators have signed on to support the measure. But it’s entirely possible the bill could go the way most bills tend to go in the state legislature, to languish in subcommittee and die a slow, quiet death.

When it comes to why the state is pushing so hard to replace the prison, James is deeply skeptical of Governor Charlie Baker. Throughout our conversation she often pondered why now, and why this prison?

“This man is just intent on moving ahead like a steam engine in building this prison,” she said. “We can only chalk it up to he owes people favors and this is how he'll start to repay the favors before he decides what else he wants to do with the rest of his life. But he's not going to do it by building a prison that kids in my neighborhood could potentially land in when we have much better ways.”

As we walked to the Worcester House of Corrections, where we’d be greeted by barbed wire, heavily armed guards, a drone overhead, and disconcertingly friendly prison brass, I talked at length with James’ daughter Sashi, who marshalled the march and took pictures. Both her mother and father had spent time in prison and I asked her what it was like, growing up with incarcerated parents.

“Well I didn't know what Father’s Day was until I was about twelve and then when my mom went to prison I was headed to college, I was a little bit older, and I was also under the impression that at the end of the day we all end up in prison, so I thought that it was just my mom’s turn, and then eventually I would be in prison at some point,” she said. “But I didn't understand that really we were under a system of oppression until my mom came home.”

Bill Shaner used to work at an alt weekly called Worcester Magazine but it was bought by a media conglomerate and destroyed so now he writes a newsletter called Worcester Sucks and I Love It.