Approaching perfection

The best of David Berman

Hello and welcome to the latest in the Hell World Top 5 Songs thing. Today we're talking about the late great David Berman. This one is even longer than usual so I'm sorry or you're welcome about that. Thank you as always to another great lineup of contributors. I'm lucky to have so many talented friends and/or colleagues.

If you missed previous editions check out the pieces on Jason Molina, The Cure, Elliott Smith, R.E.M., and Weezer.

If you appreciate what you read here please consider a free or a paid subscription. Thanks for reading either way.

Here's a playlist to listen along to.

Allie Pape

David Berman was one of us. Moved in with his buddies from college, worked as a museum security guard. Went to grad school for poetry, published a small-press book that few people read. Had a drug problem, got sober. Got married, split up. Owned a failing small business. Was big into the Tennessee Titans. Anonymously argued with strangers about politics on Reddit. Yes, he made acclaimed records, but they were never all that successful; for most of his career, he was considered a satellite act to his old roommates' band. No one thought he was an outstanding technical musician, least of all him. He didn't tour or play live shows until he was nearly 40. Even being the subject of a documentary didn't raise his profile. He is the rare artistic success story who actually got to live his life, largely untouched by either fame or the ache of its lack.

The elliptical nature of Berman's music attracts a certain type of person, one who's close with their words, quick to defuse with a joke, a bit of wry wisdom. Whose mirror of the world can reflect magnificence or barbarity, but rarely both at once. When he passed, I was taken aback by how many writers and musicians I admired, of varying tastes and sensibilities, emerged to express heartbreak. It seemed like an invisible substratum comprising everyone and everything that mattered suddenly turned visible, flashing a notification that its central node had vanished. Nearly five years on, it still feels like something crucial to the world's understanding of itself is missing.

5. People

The sonic companion to my favorite of Berman's poems, The Charm of 5:30. A perfect summer day really can solve everything, if you'll only let it.

4. Margaritas at the Mall

With hindsight, many believe the Purple Mountains record was a suicide note; I think that's wildly simplistic. But this song absolutely is. It is uncompromising in its heartbreak and rage at a feckless divine. It came into my head after watching both The Zone of Interest and Barbie; its despair has range.

3. Room Games and Diamond Rain

The first verse might be the most exquisite expression of love ever put to song. The rest is about the terror and inevitability of fucking it up. Any relationship worth a damn will die and be reborn a thousand times, until it's six feet under or you are, and that's the best we could hope for.

2. How to Rent a Room

Berman quit music after revealing what he called his "gravest secret": his monstrous father, a corporate lobbyist who fought environmental and labor causes so viciously that he was nicknamed "Dr. Evil" in a 60 Minutes story. He never wrote a song that was overtly about his dad (even as he beautifully memorialized his mom), but for anyone raised in an abusive home, the quiet anguish in "Should've checked the stable door for the name of the sire and dam" is impossible to miss. The chalk outline where a decent parent belongs should mean a lot less than this. It never does.

1. The Wild Kindness

The present moment crystallizes every time I hear those hopeful, hesitant keyboard notes. On one of the hardest days of my life, they emerged like handholds. The world did not keep its word to David Berman, but his words always keep theirs to us: the horror, the magnificence, the compassion, the mystery, they're all part of a target that we can't see. Someday, we'll never have to be scared again.

Allie Pape is a features editor, most recently at Business Insider, and a freelance critic whose work has appeared in Vulture and the San Francisco Chronicle. She is currently looking for work after BI's layoffs, if you happen to be hiring.

Sarah Larson

People

People, from American Water, is to me perhaps the ultimate Silver Jews song, and probably my favorite-favorite in a sea of favorites. It’s funny and wise, you can groove to it, it’s full of wry, brilliantly observed details, a perfect blend of everything I love in David Berman’s music. It describes some real pleasures – “It’s sunny and 75 it feels so good to be alive,” a rainbow from a garden hose – and wry aren’t-we-humans-funny moments. My favorite of all his lyrics is in this song:

People ask people to watch their scotch

People send people up to the moon

When they return, well, there isn't much

People be careful not to crest too soon

Beautiful, gently hilarious, so him. The more I age with these songs and these lyrics, the more I think about sensitivity and its role in Berman’s life, and in my own; his songs have many references to staying in, going out, embracing or escaping the world outside, and trying to reckon with emotions. Here, we have “You can’t change the feeling but you can change the feeling about the feeling in a second or two,” some staring at the ceiling, a quixotic notion of painting the dining room and having people over. But the song ends on a note of “Come on baby don’t stay inside, everybody’s comin’ out tonight,” so things are going in a good direction.

Candy Jail

Candy Jail, with its peppermint bars, peanut-brittle bunk beds, and marshmallow walls, might be the Berman song that most overtly displays his gift for alchemizing pain into beauty, humor, color, palatability. It evokes addiction – the warden knows your favorite brands, and he really listens and understands – and makes me think of anything we use to escape; candy is bright and pretty and fun but also it’s also gross, an illusion of joy that can quickly feel bad. (He does something similar on Margaritas at the Mall – we don’t have God or meaning, just purple, orange, acid green, peacock blue, and burgundy, in booze, and at the mall.) Like so many great Berman songs, it also, to my ears, has a frisson of a classic earlier song – in this case, in the early ooh-ooh part, Roy Orbison’s I’m Hurtin,’ which, imagined or intentional, delights me. And hurtin’, of course, is what directs us to candy jail in the first place.

Trains Across the Sea

I first became aware of Berman at UMass Amherst, where he was an MFA poetry student and I was an undergrad, around 1994. The poetry program, orbiting around the great James Tate, was fantastic, and the grad students brilliant, and it was a heady time, with English-major creative-writing hopefuls like me, many of us into terrific and shaggy indie rock, taught by the likes of Berman and Joe Pernice. Starlite Walker, recorded with local and beloved members of New Radiant Storm King, felt like poetry set to music, and it excited me then and still does now, making me grateful for that time, those people, that place. Trains Across the Sea feels like a dream and a poem and a song that all take flight together – much like a train across the sea would have to, I imagine. The lyric “In 27 years, I’ve drunk 50,000 beers, and they just wash against me like the sea into a pier” remains goofy-profound, as does “Half-hours on earth, what are they worth? I don’t know.” In later lyrics, Berman would go on to have some good ideas in that regard.

Horseleg Swastikas

I love all of Berman’s albums, but for many years I made the mistake of not listening to Bright Flight enough, considering it too depressing – not enough levity and musical joy to balance the tough stuff, I thought. After he died, in August 2019, I spent time with other fans and friends, many of whom politely indicated that I was nuts and should get into Bright Flight, which I did. It was almost like having a new Berman album. Its songs, including this one, have become obsessions. It is depressing – drunk on the couch in Nashville, every single thought like a punch in the face—but when he wrings beauty out of it all, it hits wonderfully hard. There’s also plenty of fodder for ruminating, again, about sensitivity, depression, addiction. The narrator is inside a lot – he could tell you things about this wallpaper that you’d never ever want to know – and he wants not to care. “I want to be like water if I can, because water doesn’t give a damn.” Listening to it in the summer of 2019, after months of heavy Purple Mountains rotation, it always put me in mind of the wonderful and devastating That’s Just the Way That I Feel, and its desire for the end of all wanting—an even bleaker lyric set to a jollier tune.

I Loved Being My Mother’s Son

I Loved Being My Mother’s Son might be Berman’s bravest, rawest song, mostly free of defenses, metaphors, whimsy – it speaks simply and directly and so unguardedly that it can be emotionally devastating, summoning the exact mixture of love and pain and sorrow that grief contains, each intensifying the other. It feels like it’s narrated directly by him, rather than by an amusing him-like character, and is so agonizing and beautiful that I don’t listen to it too often because I can’t always put myself through it. But its love and vulnerability is inspiring—to be a fan of all the other things he did so well, and then to hear him singing straightforwardly about his mother’s devotion and kindness, reminds us that artists can find power and create beauty in new ways. (And I love that he has a “I loved her to the maximum” in there, a note of Punks in the Beerlight, reminding us that he’s still his same old self.) In autumn of 2019, I discussed I Loved Being My Mother’s Son with a friend and his mom on a quiet Canadian island, looking out at the water, and during this conversation my friend’s mom pleasantly announced that she would be happy to have the song played at her funeral. My friend and I recoiled at the intensity of this idea, and then all three of us chuckled at the beautiful agonies of life, which seemed just about right.

Sarah Larson is a staff writer at the New Yorker.

Justin Sayles

5. Send in the Clouds

There are like five American Water songs that could’ve taken this spot: We Are Real (I’ve been meaning to get a “All my favorite singers couldn’t sing” tattoo for for a while), The Wild Kindness (a song I’ve long felt is one of Dave’s best, which was confirmed by Bill Callahan and Will Oldham covering it), People (as my friend and fellow Berman head Zak reminds me, “I love to see a rainbow from a garden hose lit up like the blood of a centerfold” is just perfect, just perfect) – hell, even Night Society (that riff gets stuck in my head at least once a week). But today, being forced to commit, I’m going with Send in the Clouds, one of the hardest songs in Dave Berman’s catalog – and the one that includes the all-time line: “I feel insane when you get in my bed.” (Extra immortalized in one of the great LVL UP songs.) That drum break, that guitar, that soi disantra shout-along at the end – it’s Berman and Malkmus at the peak of their collaborative powers. Good thing monsters can get along sometimes.

4. All My Happiness Is Gone

I had tickets with a few friends to see Dave in fall 2019. It would’ve been my first time catching him live after more than a decade and a half of listening to him. In the months before he was supposed to play that show, he released his first album in a decade: the self-titled Purple Mountains record. The songs on it were excellent in a way his always were, but more direct than much of the classic Silver Jews stuff. There was a strange dichotomy listening to those songs: musically beautiful, lyrically pitch black, as he sang about depression and loneliness in more naked terms than he ever had before. In the light, perhaps we should’ve seen it coming. But it still hit like a cannonball to the stomach when news came that August that he died by suicide. A day later, the venue refunded me for the tickets. I put the money toward getting the opening lines of this song tattooed on me, along with rolling purple hills.

3. We Could Be Looking for the Same Thing

Dave Berman doesn’t get enough credit as a romantic, but for my money, songs like Tennessee and I’m Getting Back Into Getting Back Into You are top-tier mixtape-for-a-girl fodder. It’s probably no coincidence that they feature his wife, Cassie, on backing vocals. Same goes for the sweetest song in Dave’s catalog, the last track on the last record he released under the Silver Jews name, We Could Be Looking for the Same Thing. It’s a plea for sprawling domestic bliss, as ”the days turn the weeks into months of the year.” But it’s a soft-sell for spending eternity together, predicated on the idea that the object of his affection is “not seeing anyone.” That it comes against the backdrop of a pristine, saccharine Nashville production, likely made some Joos fans who arrived at Dave’s music via Pavement bristle. But to my ears, it only adds to the romance and makes me wonder what could’ve been had he chosen to fully steer into that lane.

2. How to Rent a Room

One of the best songs in his catalog is also among his most important biographically. How to Rent a Room is first and foremost raw invective aimed at his rotten lobbyist dad. (Even if it’s not the most vicious thing he said about him publicly.) But it’s also the opening song on the record where Silver Jews became more than just that Pavement side project. The Natural Bridge is littered with the kinds of brilliant one-liners that turned Dave into a reluctant folk hero, and nowhere is that more apparent than on How to Rent a Room: “No, I don't really want to die. I only want to die in your eyes” may be the best album-opening couplet in the Silver Jews discography (and given the next song on this list, that’s saying a lot).

1. Random Rules

I tried everything in power to not put this song on this list, or even not at number one. It’s too basic, too obvious. A real fan should have The Wild Kindness or Trains Across the Sea, right? Except here’s the thing, Dave wasn’t just approaching perfection with Random Rules, he achieved it. It’s one of the great American songs, anchoring one of the great American albums. I don’t know what I can add to the conversation about a song that’s so haunting, yet so inviting that I’ve even heard multiple stories from friends about Tinder bros putting the opening line in their bio. (Happy upcoming 40th to all those guys, I guess.)

I got into Silver Jews the way I imagine many of us did in the pre-Obama years, on the recommendation of a friend in college. He had previously tried to get me into Spiral Stairs and Sebadoh, and they were great, but they didn’t stick for me. But when I bought a copy of American Water at Newbury Comics and put it into my busted Altima’s CD player, it took me only one verse of Random Rules to know this song and this artist would be a part of my life forever – or, to borrow one of this songs many brilliant aphorisms, that no highway could bring me back.

Justin Sayles is a writer, editor, and producer at The Ringer.

Em Cassel

There’s a track I love on LVL UP’s 2014 record Hoodwink’d – an album I played so many times at home and on long drives I once had an honest-to-god fight with my roommate about it – that opens “‘I feel insane when you get in my bed’ is something sweet that the Silver Jews said.” That’s what led me to American Water, and I was happy to drink. Its meandering, jokey rhythms were right for afternoons spent biking around Somerville, MA, getting drunk at Highland Kitchen and Trina’s and doing whatever else, but there was also the mournful current running through it, a melancholy that hit me right in the ennui of being 23. It was matter-of-fact about sadness; sadness was a matter of fact. And then, you know how it goes, I sought out David Berman’s other Silver Jews albums, I thought about getting a tattoo of a cricket or a rabbit or a depressed pony, I tried and tried to find a print edition of Actual Air. Your early twenties are also when funny guys with substance abuse problems are their most captivating although in my experience that never really stops being true.

My friend and colleague Jay Boller was one of the last people to interview Berman in 2019, in the short time between the release of the Purple Mountains record and his untimely death. Jay had just gone through a really hellish few months himself– “my year of dead friends and personal woes innumerable,” he called it in the preamble to their conversation – and that colored the interview, which was conducted over email per Berman’s preference. He talked about his backyard in Nashville. He sounded forlorn. He said he wished he’d written the Toby Keith line about not being as good as he once was but being as good once as he ever was. He was having trouble playing the new songs without weeping. He gave the email interview an A- grade.

“Final question,” Jay wrote. “Think I’ll ever be happy again?”

“I am certain of it,” Berman replied. “It's going to be such a surprise.”

By the time we published the Q&A, he’d already killed himself. Four and a half years later, I still think about that interaction almost every day.

Anyway, here are the songs:

1. Long Long Gone

Berman is our patron saint of wry couplets, and it’d be a fool’s errand to try and rank them, but,

O Lord! Please come down from the mountain

Some of us are broke and having problems

would for sure be in my top five.

2. Advice to the Graduate

I’m a sucker for tracks in which dubiously qualified lyricists dole out their wisdom for living (Composite Character, Thou Shalt Always Kill, etc.). Advice to the Graduate is a more abstract and non sequitur-y entry in this canon which is as it should be. Plus, like, the way Malkmus and Berman’s voices overlap and weave around one another… ASMR for sad sacks. Just perfect. Although the third drink has never led me astray personally, don’t know what that could be about!!!

3. That’s Just the Way I Feel

I’ve spent a lot of time (too much!) wondering whether and to what extent Purple Mountains was intended to be a coda to Berman’s career (and life), and it’s maybe too easy to look back on the record knowing what we know now and give its lighter moments greater gravity than he intended. That being said, this jangly, funny, wordy number used to strike me as one of the “more” “upbeat” songs on the record, but I’ve been thinking a lot about all the ways you can interpret “the end of all wanting is all I’ve been wanting.”

4. I’m Getting Back Into Getting Back Into You

No law against loving a straightforward little love song.

5. Like Like the the the Death

Everything on American Water is perfect, but the repetition and the imagery and the ruminating on death have always made this one a particular favorite. Besides, someone else is bound to pick Random Rules, because that’s the most perfect one. Make sure Random Rules goes on the playlist.

Em Cassel is a Minneapolis-based writer and editor and one of the cofounders of Racket MN.

Jesse Locke

Suffering Jukebox

In my early 20s, I lived in a downtown apartment in Calgary, just off the main drag, where most days began with the sound of my roommate Keith’s bong rips. Keith probably could have been a professional music journalist if he wanted to be, so he jumped at the opportunity for a phone interview with David Berman around the time of Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea. That album was the first one I heard by the Silver Jews, and it will always hold a special place in my heart. Despite the Babars on the cover, the goofball humor of Candy Jail, Party Barge, and San Francisco B.C., or even the romantic contentment of We Could Be Looking For The Same Thing, there’s a dark current of emotional turmoil flowing just below the surface. This is surely by design, five albums deep into the discography of a cowboy poet dressed up as an indie rocker who loved undercutting devastating lyrics with punchlines.

The second verse of Suffering Jukebox is my favorite moment on the album because it taps into a kind of depression that initially feels specific to Berman, but ultimately applies to any artist wallowing in their own misery until it subsumes them. If you think of yourself as a “suffering jukebox,” perpetuating personal trauma for the sake of artistic expression, “all that mad misery must make it seem true to you.” There’s some trademark self-deprecating, tongue twisting wordplay when DCB hopscotches through “You got Tennessee tendencies, and chemical dependencies. You make the same old jokes and malaprops on cue.” Yet that use of the word “malaprops” is pretentious on purpose, potentially alienating the listener in the same way as the artists he’s critiquing. Such a sad machine.

The Wild Kindness

After spending time with Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea, I quickly waded backwards to American Water. At that point in my life, I was a skateboarding journalism student taking creative writing classes and trying to figure out my whole deal, so naturally Berman’s poetry spoke to me. There are probably going to be a few other people on this list who include American Water’s Random Rules and its immortal opening lines: “In 1984, I was hospitalized for approaching perfection.” Instead, I’d like to shout out the album’s final song, closing its thematic loop with lyrics that are just as impressively evocative.

When Berman sings about “oil paintings of X-rated picnics,” “dying his hair in a motel void,” or even “four dogs in the distance,” my brain pops up those images faster than DALLE-3. But when I dig a bit deeper into his feeling of being “perfect in an empty room” (at his most content when he’s alone and there are no expectations on him) and the strength it takes to “spurn the sin of giving in” (knowing about his previous suicide attempts), The Wild Kindness takes on a whole other quality of resilience. The four horses of the apocalypse aren’t here just yet.

Punks In The Beerlight

In 2005, I was still going to college while starting my days of feast-or-famine as a freelance writer: reviewing albums, interviewing bands, and trying to develop a voice like my hero Byron Coley. That same year, Berman linked back up with the members of Pavement and guests like Will Oldham for the country-fried drinking album Tanglewood Numbers.

You could probably call the album’s opening song Silver Jews’ biggest “hit,” if such a thing exists, but there are a lot of reasons why I wanted to pick it. First of all, “I loved you to the max” is one of the greatest gang chants of all time. Berman slyly revisited that lyric in the Purple Mountains song I Loved Being My Mother’s Son (“I loved her to the maximum”), which not a lot of people seemed to notice. In Punks in the Beerlight, he references “smoking the gel off a fentanyl patch,” then boldly declares “Adam and Eve were Jews.” No one else could do that and get away with it.

Best of all are the lyrics duetted with his then-wife Cassie, creating a domino effect with each tumbling tile: “If it gets really, really bad. If it ever gets really, really bad. Let’s not kid ourselves. If it’s really, really bad.” Few other artists have sung about their struggles with depression and addiction so openly, never mind channeling them into a timeless, cathartic, totally ripping indie rock anthem.

All My Happiness Is Gone

I think it’s fair to describe American Water as the masterpiece of the Silver Jews era. Yet much like Twin Peaks: The Return did for David Lynch, Berman’s comeback as Purple Mountains allowed him to create a culmination of his work by removing it from the vacuum of cultural contexts or expectations. When the Purple Mountains album was first announced with All My Happiness Is Gone, I fell in love with the Mellotron-drenched motorik pop jam immediately, even going so far as tattooing “friends are warmer than gold when you’re old” on my arm. Knowing that the chorus hook is an interpolation of I Melt With You makes it even better.

I wrote a 5/5 review of the Purple Mountains album for my local alt-weekly, which Berman responded to with a “thank you, sir” tweet that still warms the cockles of my heart. Then, he was gone. To grieve his passing, I organized a tribute show with the help of my brilliantly talented ex Kritty Uranowski, Berman’s friend Vish Khanna, the Grundy brothers, and the dozens of other musicians who took part. A Stone for David Berman happened on the night Purple Mountains were supposed to perform in Toronto, and it was a perfect way to sit shiva.

A Cowboy Overflow of the Heart

I struggled for most of 2023 with my own depression, finding it harder than ever to spurn the sin of giving in. Listening to Berman’s voice during that time was bittersweet, and returning to Purple Mountains seemed almost impossible. Those songs reminded me of the mistakes I made in my last relationship, the hurt I caused, and how Berman responded to similar challenges only a month after his comeback album was released. Needless to say, Nights That Won’t Happen was too much to take.

Robbie Chater from The Avalanches spoke about his own struggles in a 2021 Facebook post, two years to the day that Berman died by suicide. Referencing his experiences in “another hospital, another detox” and how corresponding with Berman pulled him back from the brink, Chater shared the origins of their collaborative song. A Cowboy Overflow of the Heart sets DCB’s poetry to a classic Avalanches backdrop of dreamlike melodies punctuated by children’s cheers, and it features some of his finest lines.

Late in the day

When the options are gone

When the seatbelt’s the only hug you’ve felt in weeks

When wrong numbers are the totality of your social life

The obscure strategies of wildlife

Only flummox the hell out of you, kid

What I’ve learned from the experiences of pushing everyone in my life away is that we’re all beaten down by the world sometimes, but we’re stronger when we tackle it together. Don’t let a quest for personal perfection become an enemy of the goodness that’s inside you, kid.

Jesse Locke is a writer, drummer, and skateboarder living in Vancouver, BC. He writes for Pitchfork, Bandcamp Daily, The Wire, Aquarium Drunkard, and elsewhere.

Keegan Bradford

1. Trains Across the Sea

2. The Wild Kindness

3. All My Happiness is Gone

4. Inside the Golden Days of Missing You

5. Suffering Jukebox

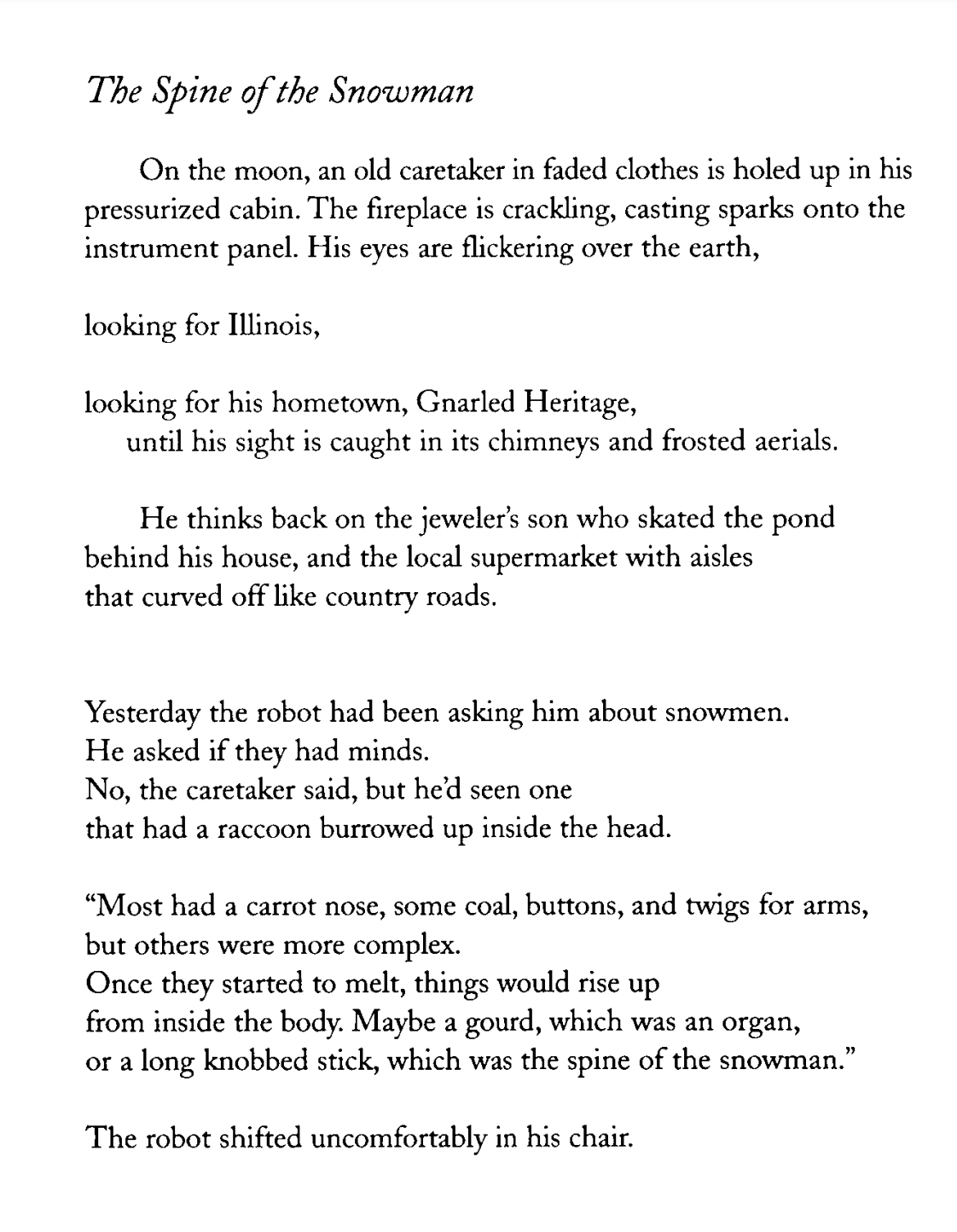

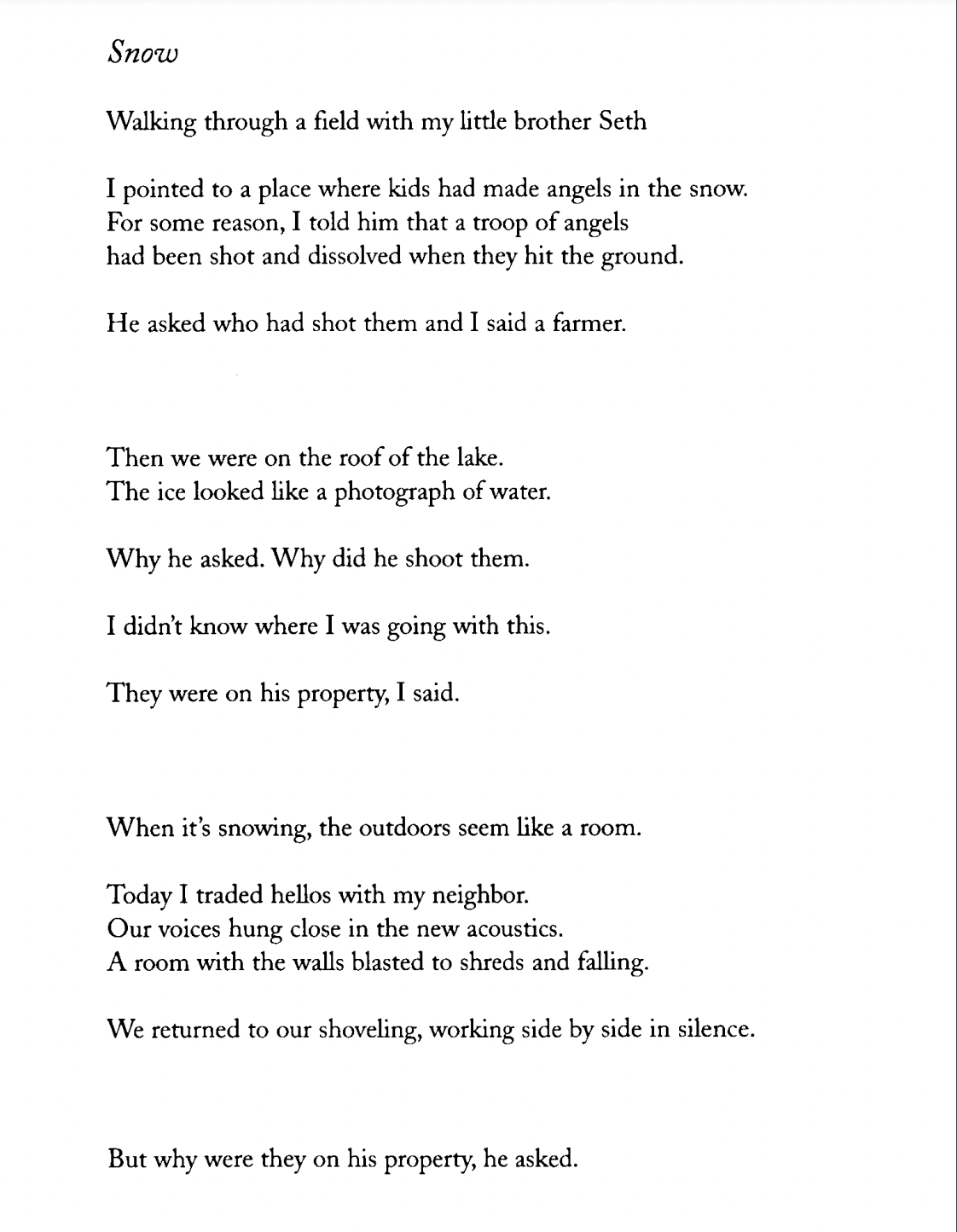

Some people say music lyrics are a kind of poetry. That is wrong. Lyrics are a totally different thing and I wouldn't want to read them on paper. David Berman is pretty much the only exception to this. He is the only person who was as funny as as he was sad, and he was really sad. The best song is Random Rules. It's one of the best songs ever written in the English language, and I assume all of us will have it on our lists. So assume that that's my ghost man on first. Dave wrote a poem about snow that I read to my class every year when I was a teacher. You should go read that poem and then walk around a little bit and get a coffee or a beer or whatever and just be quiet. Some writers make me want to write; Dave always just made me want to listen.

Keegan Bradford is a writer and musician living in Portland, OR who plays in the band Camp Trash.

Marianela D’Aprile

I always hear in David Berman’s music a very dudely, self-consciously un-self-conscious bravado. I love feeling full of that when I listen to it. It’s funny because I also think of Berman’s music as suffused with an amorphous resistance to the performance of gender, originating in that very first gender-full relationship with his union-busting, working man–hating father. It was strained at best; in a 2009 open letter titled My Father, My Attack Dog, Berman more or less says that he brought Silver Jews to an end because he realized they’d never make up for the harm his father was doing to the world. Meaning that whatever music-making he had been doing for the previous two decades – the Jews had been playing together since 1989 – was motivated, if not solely, then substantially, by the desire to atone for his father’s sins. As though he could. As though they were his own. Into that impossibly black, gaping, endless abyss, Berman threw his music and, eventually, himself. The tragedy of his death laces every single one of his songs now; I can’t listen to them without thinking about where he ended up with all of it; of the pain of growing up and being grown without anyone to emulate, of having to figure it out himself and, as if that weren’t difficult enough, also take on the moral debts of the person who left him so unmoored in the first place.

How to Rent a Room

I don’t think it’s a stretch to say Berman here is singing to the elder Berman, burdened by the task of living so far, unable to get out from under the boulder placed on his shoulders by an original sin committed on his behalf. This song is like swimming in a waveless ocean: so pleasant, so even and easy – until your leg goes through a cold current or grazes a piece of seaweed.

Tennessee

I spent the back half of my childhood in Tennessee and generally associated it and its attendant institutions with the horrid, stifling conservatism Berman chafed so hard against, so when, after he died, the Tennessee Titans paid tribute to him on their Jumbotron – “Nashville (and the world) will always love David Berman!” – I cried a lot. It was a little miracle, and maybe a testament to Berman’s not-unwavering belief in music’s capacity for transcendence.

We Could Be Looking for the Same Thing

There’s a funny little hope, a playfulness in this song. A sense that it doesn’t all have to be so hard. Are we looking for the same thing? We could be! Let’s try to be, maybe?

We Are Real

This is my favorite Berman song. I don’t know what to say about it other than I listened to it a lot when I was in a relationship with a man who was married and pretended I didn’t exist except for when it was convenient or useful for him to do otherwise. The dogged insistence of that line, “we are real,” over and over like a prayer, felt exactly like my own.

Snow is Falling in Manhattan

I dare you to listen to this and not feel like a drifting snowflake, swaying easily from side to side, hovering high above the city until you fall down into a bed of a trillion of your closest friends.

Marianela D’Aprile is a writer. She lives and works in New York City. You can see her work compiled on her website and read her Substack.

Luke O’Neil

Advice to the Graduate

New Orleans

Trains Across the Sea

The Wild Kindness

Imagining Defeat

Horseleg Swastika

Random Rules

Margaritas at the Mall

You have to sneak up on it.

Writing I mean.

No that’s not right. Let it sneak up on you is the thing. Turn your back to it. When you’re trying too hard to fall in love the universe senses it. Forestalls you. Hamstrings you.

“Your third drink will lead you astray. Wandering down the backstreets of the world.”

There's a pocket of time between one and three drinks of an evening where everything I’ve ever really written was written. A kind of powering up. Super hero serum. I know that this is a dangerous lie but you understand me.

The only thing that can defeat me is my nemesis the fourth drink.

I'm inside of there as I write this but I’m a scuba diver with a depleted oxygen tank.

The intervals between the steps have tightened of late.

Half hours on earth

What are they worth?

I don't know.

In 27 years

I've drunk fifty thousand beers.

And they just wash against me

Like the sea into a pier.

A half hour when you’re drinking is nothing but a half hour when you are not is 27 years.

25 tops.

Here’s something I wrote once:

“Yesterday was our wedding anniversary which I spent like I have the last four of them thinking all day about suicide. Now hold on a minute I say that because it's the date of David Berman's passing.”

That’s not really anything.

I’m going to repeat some things I’ve said before because it’s getting hard to breathe and I need to surface.

David Berman was a poet which sounds weird to say because we don’t really have poets anymore. Whenever I think about him a couple lines come to mind from the poem Imagining Defeat in his book Actual Air that went like this:

I reached under the bed for my menthols

and she asked if I ever thought of cancer.

Yes, I said, but always as a tree way up ahead

in the distance where it doesn't matter.

I used that line as the epigraph to one of my books.

That’s not really anything.

I would have read Actual Air in 2000 or so when I was just breaching into all of this just after college which is around the most devastating time you can read a devastating collection of poems. It’s like how they say drugs and alcohol are particularly bad for young brains because they aren’t fully developed yet and it works sometimes like that with poetry too. Poetry much like drugs and alcohol is a delivery system for either despair or exultation or both at once and if you’re too young you don’t know what to do with either of those things.

If you’re old too.

That poem just now reminded me of this bit I wrote in one of the chapters from the Hell World book I’ve plugged too much on here sorry but it went something like this:

“Everything we do today comes at the expense of the future. That can be little things like how last night I basically ate an entire loaf of bread…Or it can be taking pleasure or comfort in all the things you know you shouldn’t do but nonetheless feel good right now in this moment and tomorrow is not your problem. Someone else is going to have to deal with it and even if that person is actually you it’s still you tomorrow and you don’t know that guy so let him figure it out.”

I guess tomorrow isn’t David’s problem anymore and that is still unmooring to everyone who loved him and loved his work but I am personally glad I still have tomorrow to not worry about today and I hope you are too because you never know it could actually end up being really good?

No one can tell you that it’s not going to be a really good day. Tomorrow that is.

“I'm gonna shine out in the wild kindness. And hold the world to its word.”

All our beloved sad dead boys were so funny but David was the funniest of them all. I said something like this in the Jason Molina piece. There’s nothing much funnier than being dead I guess. The last joke. The one single joke whose punchline we all get.

Are forced against our will to get.

“On the last day of your life don't forget to die.”

I don’t want to say this next one is his funniest line because there are far too many to pick – and I also have the biting and bitterly hilarious Margaritas at the Mall on my list – but one of the funniest lines comes in New Orleans.

“There is a house in New Orleans. Not the one you've heard about. I'm talking about another house.”

I don’t want to be too prescriptive here but Random Rules is the keystone to all of this we’re talking about. If the opening lines – very obviously and widely celebrated and in my opinion up there with Molina’s Farewell Transmission – of “In 1984, I was hospitalized for approaching perfection. Slowly screwing my way across Europe, they had to make a correction,” don’t immediately grab you then maybe you aren’t going to get his whole deal and that’s absolutely fine.

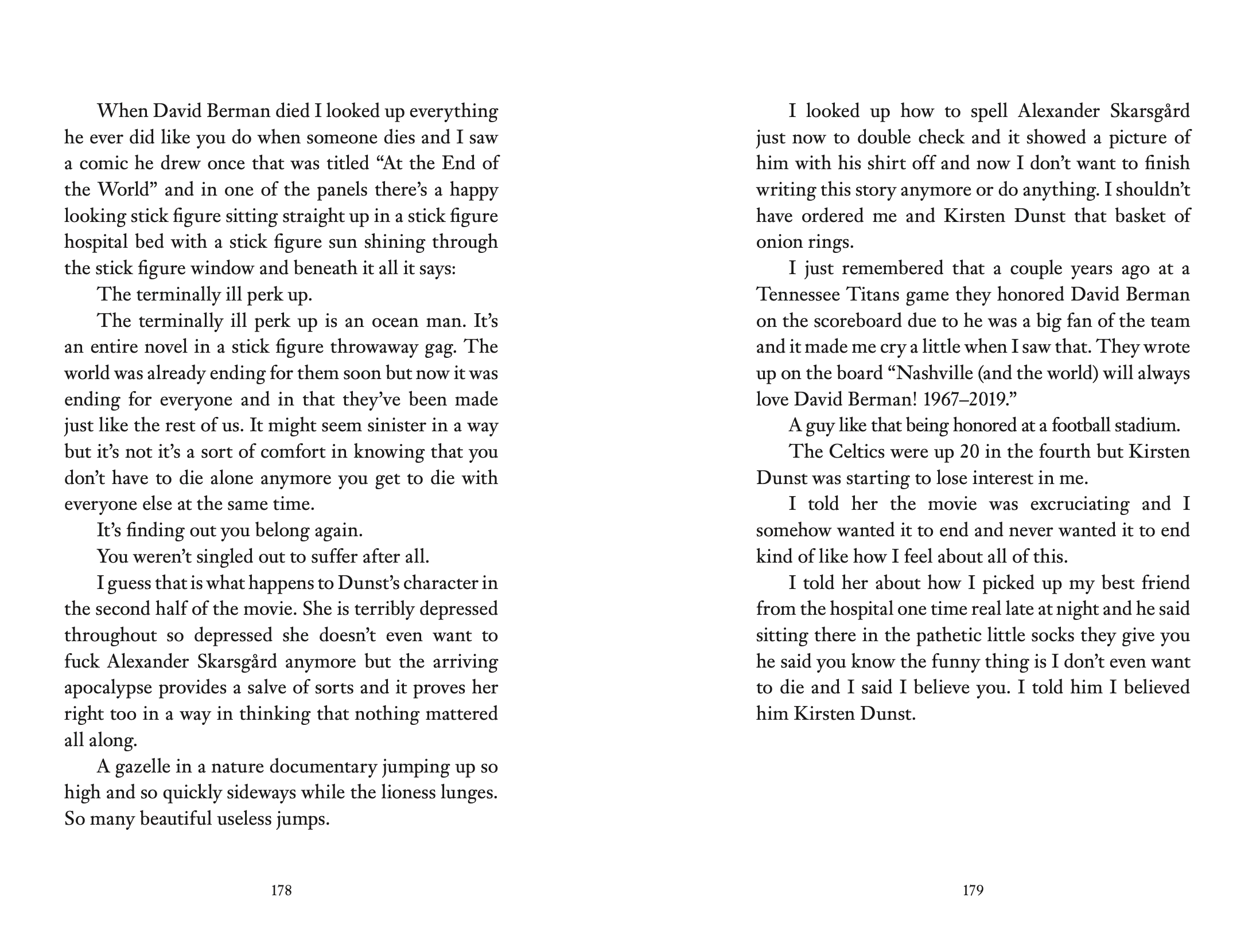

I only reference a handful of celebrities and such in my book A Creature Wanting Form – unless you count God and/or Jesus Christ who come up more than is seemly – but two that figure in one story I like a lot are David Berman and Kirsten Dunst which is a pretty good measure of the kind of brain I’m dealing with. Not unlike Berman’s in a way I suppose. Morose and horny. Or sort of morosely horny rather.

“But nothing can change the fact that we used to share a bed”

One of the stories – A stick figure throwaway gag – goes in part like so:

Margaritas is such a masterclass in walking the line between existential despair and visceral disgust at the garishness of late Americana.

This section here I believe might be his finest work. Out of everything. All of the poems and all of the songs.

How long can a world go on under such a subtle god?

How long can a world go on with no new word from God?

See the plod of the flawed individual looking for a nod from God.

Trodding the sod of the visible with no new word from God.

It should not hit as hard as it does. Typically an identical end rhyme scheme comes off as lazy and sounds off-putting to me but here it’s a continuously landed punch. Thudding and thundering. An effect abetted largely by the internal rhymes disrupting our ear. Obfuscating.

“Such a subtle god.”

“The prophets had something I didn’t have, which was a line on God,” he said in an interview published a month before his death.

“They had communication. That’s why I call it a ‘subtle God.’ I’m being sarcastic. It’s kind of angering – you get to the point that if you do believe in God, you get angry at God, and then nothing happens. Although I’ll never rule anything out; I’m not an atheist in any way.”

It’s been two thousand years since we’ve heard anything. I think maybe that was the only word we were ever meant to get. We have to settle for prophets like David Berman now and that seems like a fine trade.

Luke O’Neil runs this newsletter. His most recent book A Creature Wanting Form is good and you should read it.

Rachel Yara

That’s Just the Way That I Feel

I first listened to David Berman almost too late. It was summer 2019 and I was 20, working at a bagel & coffee shop so self-consciously branded with Gen X indie rock nostalgia it was literally named Pavement. We were young and rowdy and mostly just hanging out with our friends, spilling liquid eggs on our band T-shirts and taking any lull in business as an excuse to run to the back and queue up a few more songs. Purple Mountains’ first and only record played often.

Some songs are so upbeat, you almost forget the lyrics are so depressing. This isn’t true of That’s Just the Way That I Feel. Over propulsive rhythm and Pentecostal piano licks, his despairs are cataloged plainly:

You see, the life I live is sickening.

I spent a decade playing chicken with oblivion.

Day to day, I'm neck and neck with giving in.

I’m the same old wreck I've always been.

His dry voice cuts through, with no elaborate metaphors offering plausible deniability. And yet, in a workplace where “I am going to kill myself” was code for “I’m going to go smoke a cigarette when the rush is over,” his lyrics felt like inside jokes and we talk-sang along.

Blue Arrangements

Berman’s death sent me into obsession, and his dense lyricism gave me plenty to untangle. Is Carbon Dioxide Riding Academy a joke about blue bloods? Does “a boy raises himself” refer to his disavowal of his lobbyist father’s work? How did he feel about Malkmus’s voice dominating words that feel so personal to him?

Sometimes I feel like I'm watching the world

and the world isn't watching me back.

But when I see you, I know I'm in it too.

The waves come in and the waves go back.

American Water careens between looking outward and inward, between historical allusions and intimate flashes of memory. It makes me want to write a dissertation but also it just sounds awesome and it rocks.

Dallas

Oh Dallas, you shine with an evil light.

How did you turn a billion steers

into buildings made of mirrors,

and why am I drawn to you tonight?

Berman loves to work out his comorbid disgust for and fascination with a changing American landscape. He also loves to cut the tension with a cum joke. When asked about this, he said “The Natural Bridge has a lot of privacy issues going on inside.” Vague, but I take it as a comment on the extremes of exteriority and interiority, on his preoccupation with place and the self that lives there. You look in someone else’s window, and see yourself reflected back.

The Charm of 5:30

I am cheating by including a poem, but it is my favorite poem ever written. A perfect day, the kind where you find a knickknack in your pocket that feels like a treasure hidden by your previous self. The kind where you hold the soda you drink every day up to the light and discover its red hue. Where everything is new and beautiful.

Still, Berman’s happiness seems to register as surprise at misery’s absence:

It all reminds me of that moment when you take off your

sunglasses after a long drive and realize it’s earlier

and lighter out than you had accounted for.

This is what a good day feels like in the midst of depression. The world is suddenly bright and full. And you desperately cling to it, document it, try to sear it in your mind, because somewhere in the future the world will feel gray again and you will need to remember having a beer in the park with your friend.

New Orleans

In an interview he said that being remembered is scarier than being forgotten "because you’re frozen." This song feels like a reckoning with that, with living with ghosts and knowing you will be among them someday, haunting someone else. It’s also fun – fuzzy, silly, anthemic. If I could be trapped inside a song, it would be this one. "You can’t say that my soul has died away."

Rachel Yara is a bookseller and writer living in New York.

Harry Cheadle

Random Rules

American Water is like Berman 101 so it makes sense the opening track is like an intro text. Everything we love about Silver Jews is here — the laid-back vibes, the fun little guitar riffs, the elegant wordplay, the depressed-guy horniness (“Baby we’ve got two lives to give tonight.”) There are too many lines here to quote but my personal favorite is “I asked a painter why the roads were colored black. He said Steve it’s because people leave and no highway will bring them back.”

Suffering Jukebox

I like the old low-fi records Berman put out, but I just find the slicker, more produced later albums a little easier to return to. This is a song I first got into because of the neat-o guitars that remind me of Dire Straits or some shit, but the metaphor at the center is fairly complex. Not only is the titular jukebox sentenced to play sad songs, it’s stuck in a happy town that doesn’t want to hear its downers. The jukebox is an artist, “all filled up with what other people need” but nonetheless walled off from the world because the “people in this town don’t want to know.” Damn.

Sleeping Is the Only Love

“I had a friend, his name was Marc with a C. His sister was like the heat coming off of the back of the old TV.” An incredible, all-time description of young lust, casually tossed off.

I Remember Me

This is maybe the clearest story Berman even wrote, and on its surface the stupidest — a saccharine love song interrupted 80% of the way through (spoiler) by a truck hitting the main character. But it’s not a story about the random cruelty of life, it’s a story about how much life just keeps on happening to you. You fall in love at a party, a truck knocks you into a coma, your love leaves (for Oklahoma, on account of the rhyme), and you keep on living for a full verse and chorus longer, long past the point of it fitting into any kind of narrative sense.

There Is a Place

Berman appeals to me, and I suspect to a lot of Guys (non-gendered) Like Me because he confronts existential dread with humor and wit. Fear of death, or really the great unknown that lies beyond death, is conquered for a few minutes by cleverness. Depression is undercut by humor. Darkness is lit momentarily by the Bic lighter of love. Even on that Purple Mountains album I can’t bring myself to listen to anymore, soul-crushing misery is lightened by straight-up puns. But there are no jokes on this song. It’s not explicit but at the same time it is quite clearly about suicide, or about the feelings that could lead one to suicide. Even Berman can’t describe it beyond a few lines, and he gives up on witticisms — by the time he’s screaming “I saw God’s shadow on this world!” at the end, I have chills, or something deeper than chills.

Harry Cheadle is a writer and editor living in Seattle. You can find his newsletter Life Inside the Bubble here.

Alex Fatato

People

I think the first time I heard a whole Silver Jews song was in a basement in Boston at a Halloween house show. The bands were doing cover sets and my friends played the song People. I moved to Nashville a couple years later, and listened to it most days biking to work, hungover, repeating, “it feels so good to be alive.” David Berman lived a couple miles north of that commute. I don’t think he crossed over from East Nashville into the college campus, country music award territory of the city often. I was too worried about being 20 to go looking for him or do anything but skim the top off that song. There are David Berman songs I listened to for years but didn’t hear until the 5th, 30th, or 100th listen. “The drums march along at the clip of an IV drip like sparks from a muffler dragged down the strip” took a couple listens to freeze me up. But the song was fun every time. Later, I’d repeat a different line to myself: “You can’t change the feeling but you can change the feeling about the feeling.”

Trains Across the Sea

I decided to listen to every Silver Jews album in order and found Trains Across the Sea. Then I bought the Drag City repressing of Actual Air. The book showed me what poetry could be. I tried to read everyone David said he liked and then read most poets who said they liked him. David wrote those poems around the time he was writing Trains Across the Sea, which he says is his “first” song he ever wrote. A Wallace Stevens interpolation folds into a measurement of time and beer in what might be the greatest lyric ever written. It’s two chords the whole way.

Friday Night Fever

When David died I scraped the internet for every interview he’d ever done. There was a lot of Johnny Paycheck worship and classic country playlist curation. My mom listened to a lot of George Strait growing up, but I tuned it out. I didn’t hear him until the Silver Jews cover of Friday Night Fever, which I didn’t know was a cover for a couple of years. Through my youth I turned my nose up at country. I grew up in Boston. Songs like Black and Brown Blues and the Strait cover opened up country the way that Actual Air opened up poetry. He gave me permission to explore and enjoy a lot of music I wouldn’t have found without him.

Horseleg Swastikas

I teach 11th graders in Boston. My favorite fad in education lately is the buzzphrase “productive struggle”. Teachers roll their eyes at this stuff. But it’s often a helpful reframe in my classroom. You have to be uncomfortable to grow and learn. Poetry, country music, and David’s voice all made me uncomfortable at some point. I recoiled the first time I heard the name “Silver Jews” and recoiled the first time I heard “Swastikas” in an indie rock song. I didn’t immediately get the scriptural or philosophical references, but that’s okay. They were there to wrestle with, work through, and love. Horseleg Swastikas is a hangover song that is anti-wallow. It hurts to be worse, and it hurts to want to be better. Wanting is the first step.

Darkness and Cold

I visited Nashville again for a week in July of 2019. I opened Youtube on my friend’s Xbox and showed him the music video for Darkness and Cold. I grinned on the edge of the couch and turned and repeated the lines to him after David synced them on the TV. The music video shows him behind his real life wife, since separated, as she gets ready to go see another man. The syllabic rhythm is perfect, almost iambic. It’s tight. It’s brutal. It’s funny. David said he wrote about an excruciating prospect to “model the imminent experience…When I’d be tormented by those thoughts I’d remind myself how much I like the song.”

I got a tattoo after David died of one of his Portable February drawings - three birds in a circle holding hands, a bird under a storm cloud, and the words “Difficult Freedom.” I’m sure he was, maybe directly, referring to a book of essays on Judaism’s significance in European philosophy. But the two words represent a throughline in his work and my life. Just because it’s hard, doesn’t mean it’s not funny, universal, or good.

Alex Fatato is a teacher in Boston that writes and performs music as Alexander.

Steve Kandell

Any attempt to write about David Berman songs inevitably turns into an exercise in writing about David Berman lines. He of course was a generational songwriter who thought about form, but no one’s canon boasts a better ratio of moments that make you move the needle back to make sure you really heard what you thought you just heard. I don’t know what this stat is called. He was a poet, but nothing felt flowery or purple, it was cocktail-napkin philosophy. The bon mots and deadpan epiphanies are invariably plain-spoken but not so plain that you’d be able to come up with them yourself.

These are some of the lines that have stopped me at various points in the past 30 years, which is so many years. There are so many others. Other people on here may be writing about the same ones; that is because they are really good.

Trains Across the Sea

“Half-hours on Earth, what are they worth? I don’t know. In 27 years I’ve drank 50,000 beers and they just washed against me like the sea into a pier.”

If David Berman in his entire too-short life wrote nothing but these two lines, he would have been worth lionizing. They are mic-drops packed so close to each other at the end of Trains Across the Sea that you don’t even have time to pick up the mic before having to drop it again. I do not read a lot of existential philosophy, is it much more effective than this? It definitely seems longer. Life may or may not mean anything so we do things to pass the time and amuse ourselves but those don’t really mean anything either, it’s all just a lot of sloshing around. Then the song ends because what are you supposed to say after that.

We Are Real

"All my favorite singers couldn’t sing."

I have only ever heard this line as a lightly shrugging apology but it was also his secret weapon. He couldn’t really sing, but in the best possible way; this could give the impression that lyrics he wrote were casual and off-the-cuff, just a guy sayin’ stuff. His favorite singers were good at this, too.

People

“It’s sunny and 75, it feels so good to be alive.”

Even the tritest move-to-LA-ass sentiment sounds like the saddest thing in the world now.

Maybe I’m the Only One for Me

"If no one’s fond of fucking me, maybe no one’s fucking fond of me.”

God, he was funny. Maybe I’m the Only One for Me is the last song on his last album and it’s a cheerful-sounding honky-tonk ode to being resigned to abject and unending loneliness. It’s weirdly hopeful (“I’ll have to learn to like myself”), but mostly the entire song lives in the long shadow of that turn of phrase. In a perfect world, no one capable of thinking of it would ever have a moment of self-doubt in their lives but this is not that world.

Steve Kandell is a writer and editor in Los Angeles.

Michael Metivier

My first exposure to the work of D.C. Berman was an essay he penned for the liner notes to The Early Year, Sub Pop’s compilation of the first two Scud Mountain Boys albums that was holy to me in college (still is). In them he dropped a line (“suburban kids with Biblical names”) I would later recognize in a Silver Jews song. It prefigured loads of other songs and poems with his elbow-throwing cadences and late-capitalism obsessions (“light-studded medical cities,” “crows wired to the sky like marred pixels”), and spoke directly to my soul by invoking “the justifiably uncelebrated Massachusetts sky.”

I didn’t know at the time that D.C. Berman was a poet like I wanted to be, a songwriter like I was desperate to be, I just knew that he nailed it. That by dissing the sky I knew so well, its dinginess hanging over so many strip-mall Friendly’s restaurants and Bradlee’s discount department stores of my youth, he was actually celebrating it, justifiably, it seemed to me.

Berman’s bit of snark at the Commonwealth’s expense remains emblematic of what I love most about his many gifts – his knack for seeing the country so clearly and rendering it so honestly. Even, and especially, when it hurt, because the particulars and peculiarities of our times can also – and often do–make us laugh.

5. Long Long Gone

This song off the Tennessee EP features a stone-cold classic country one-liner, speaking of the intertwining of sad and funny (and clever), that’s right up there with the best of them: “If cars could run on teardrops I’d be long, long gone.” The musical setting is something else, however – woozy, jangly verses building toward a horn-soaked chorus that’s impossible not to sing-shout along with: “Oh loooooooooooorrrrrrd, please come down from the mooouuuuuuuuntain. Some of us are broke and having prooooooblems.”

It’s at once self-effacing and defiant, joyous and deeply anxious. Choosing this song for my top 5 over say Dallas or K-hole or Party Barge (or any Purple Mountains song) was tough, but I needed at least one pick that was chooglin’.

4. Room Games and Diamond Rain

I took Bright Flight (and Tennessee) home as a perk for interning at Drag City in Chicago in 2002. I think it’s the Silver Jews’ most beautifully recorded album. Lambchop’s Mark Nevers engineered and produced it, and a few other Lambchop alums play on it – I’m assuming the guitar solos and the electric piano solo at the end of Room Games are courtesy of William Tyler and Tony Crow, respectively, but regardless they are perfect. Of course, the words are also divine, splitting the difference between translucent and opaque. “You can make me feel like drinking wine in the shade all afternoon.” So sweet and smitten and perfect amid all the f-stops and electrified reindeer.

3. Buckingham Rabbit

Like so many others, I’ve committed a staggering amount of David Berman lyrics to memory, and a great deal of them from American Water, which is the first Silver Jews album I bought and is perfect all around. But I love Buckingham Rabbit just as much if not more for Malkmus’s loping guitar solo. My blood pressure instantly drops into a healthy range when I hear it, like it’s the first warm night of spring when I can roll my windows down and hear peepers as I drive the winding backroads, the air smelling of petrichor and the “pine perfume of hill town floors.” I want to live in its vibes forever.

2. Pretty Eyes

It’s telling, to me, that the opening lyrics of the very first Silver Jews album (from Introduction II on Starlite Walker) are, in their entirety: “Hello, my friends. Hello, my friends. Come on (in) have a seat. Come on in my kitchen. My friends take it easy. My friends have a seat. My friends don’t you know that I never want this minute to end (and then it ends).”

It’s sung with affection by two buddies, Berman and Malkmus, and it should instantly dispel any notion going forward that the Silver Jews is another sneering, irony-drenched product of the mid-1990s. It’s pretty damn heartfelt! And both its welcoming sentiment and earnest desire for connection permeate the catalog. Pretty Eyes, from The Natural Bridge, I think, is quintessential Berman. It’s got a lovely, bittersweet chord progression; a few goofy, eyebrow-raising rhymes (“blueprints, shoe prints,” “cowboy, now boy”); references to municipal/federal figures and institutions (“when the governor’s heart fails, the state bird falls from its branch”); ponderings of death and infinity; and genuine stunners like the closing lines: “though final words are so hard to devise I promise that I'll always remember your pretty eyes.”

1. The Wild Kindness

I don’t know what a “classic nitrogen afternoon” is, or if the “bluebirds lodged in an evergreen altar” are alive or wired to a Cornell box like marred pixels, among other mysteries in The Wild Kindness, but it doesn’t matter, because I never tire of wondering, of trying to understand them, maybe even coming close before the answers slip away like dreams in the first few seconds after waking up. (I might have a handle on “it is autumn and my camouflage is dying,” though – it’s related to Drag City labelmate Bill Callahan’s observation that “winter exposes the nest.” I’ve felt that.) And that’s why this song is as eternal to me as what I feel is its ultimate subject matter: the infinity embedded in every moment that we don’t want to end. And then it ends.

Michael Metivier lives in Vermont with his wife and daughters. His poems and essays have been published in Poetry, Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner, and elsewhere, and he is an editor at Merriam-Webster.

Amanda Larson

The kids have worlds inside their worlds, little clicks of glass. I know this when I sit down with them at tables, at the school I teach at, to revise their poems and stories. You have probably seen more images on a screen today than my grandparents have seen in their whole life, I tell them, and I constantly tell them to read and listen to David Berman. No other writer, with perhaps the exception of DFW, could simply cope with the reality of such virulent multiplicity of images, to use them to form a meaning that is both blasé and revelatory, a kind of neat little prayer that feels to me like a real communion with God, who is also there, I guess, all of the time.

NOW II

I am not in the parlor of a Federal Brownstone.

I am not a cub scout seduced by Iron Maiden’s mirror worlds.

I’m on a floor unrecognized by the elevator,

Fucked beyond understanding

Like a hacked up police tree

On the outskirts of town.

You could be in the parlor of a Federal Brownstone or you could not be; this phrase “I am not in,” could be followed by any location on Earth other than the one you are currently in. Berman’s poetry is inherently deconstructionist, in the breaking down of the binary not just of place, but of perspective. I am not a Cub Scout. I am not the elevator, either, who doesn’t recognize me. The poem goes on to say that turtles are screwed in the snow, and rather than be devastated by this fact, which is the sheer number of perspectives of things that seem screwed, it concludes in call to song:

Dear Lord, whom I love so much,

I don’t think I can change anymore

I have burned up all my forces at the edge of the city.

I am dressed up to go away,

And I’m asking You now,

If You’d take me as I am.

For God is not a secret.

And this is also a song.

You can tease out the tiniest thread of prayer from anything, the anything splintering down into Now II, the second now what follows now, which is impossible, because it’s another now, and now another.

Death of an Heir of Sorrows

I have not avoided certainty

It has always just eluded me

I wish I knew

I wish I knew for true

I wish I had a rhinestone suit

I wish I had a new pair of boots

But mostly I wish, I wish I was with you

The song, for Rob Bingham, is filled with wishing for what the dead can’t do. It’s not exactly an elegy; it’s not exceptionally mournful, it’s a little bit funny, as most things are. I started listening to this after learning of a death the circumstances of which were comically awful, and it was all I could listen to that sweltering July, in a certainty that continually avoided me.

Snow is Falling In Manhattan

On the Sabbath, as it happens—

Coming down in smithereens.

The song arcs and splits into chimes. The same as in Berman’s poem, Snow – “When it’s snowing, the outdoors seems like a room,” and then, “a room with the walls blasted to shreds and falling.” Like physical spaces, the definitions of words shift. The world shifts into snow, what melts. The selection of Manhattan, the busiest place on Earth, doused in stillness; the very phase itself, Snow is falling in Manhattan a declaration of peace.

Random Rules

There is no guidance when Random Rules, and here he is, leading us across it, and more importantly the other, she, is leading us across it. There are the multiplicity and the people you find across it, and the people who do not recognize that you have found them across it. Of all that shifts and changes in Berman’s lines, the almost permanent dislocation I feel across them, I think this is the only time he says, “Nothing can change,” and the follow up being “the fact that we used to share a bed.” The blistering intimacies that corral us into narratives. How horrible, they make so you can’t shake hands when they make your hands shake. Still, I love the tan line on your ring finger, what signals even if you don’t want it to, the question I have to ask about it.

Trains Across the Sea

Troubles, no troubles on the line,

and I can’t stand to see you when you’re crying at home.

I tell the students, all of the time, to be careful of where you put the I, be careful of what you declare, because too much I runs the risk of a dramatic self-assurance you can’t have at sixteen. I love how he uses the I to say what he can’t say, here. The syntax of the lines showing the variety of ways you can measure your life, the power you can feel or not. It can be evening all day long, if you say it is.

In 27 years, I’ve drunk 50,000 beers

and they just wash against me

like a sea into a pier.

Nothing has been more true than the sensory; the beer washing into you, the sun on your face on a hill in Virginia, picturing the ideal of the hill, becoming totally real.

Amanda Larson is a writer and teacher based in New York. Her first book, Gut, was published by Omnidawn Publishing in 2021.

Sam Hockley-Smith

David Berman was always going to die. I don’t mean that in the “mortality comes for us all, death is a cruel mistress” way, but in the way that the man spent so much of his career grappling with the specter of death, both in his art and in his actual life. Everyone dies, but certain people are surrounded by death’s aura even when they’re alive. We get lucky when these people give us a window into their minds, because in their death-obsession, we get glimpses of an unvarnished look at a hostile world, a lesson on how to navigate through the bullshit from someone who has it embedded in their brain that they were always going to fail (wait, is Berman the Denis Johnson of indie rock?).

Berman’s music is powerful because he always met that despair with laconic good humor and a sort of warm sarcasm that feels at once piercing and non-judgmental. In other words, to listen to David Berman, to read David Berman is to, for a brief moment, feel good about feeling bad. These five songs are not listed in any order. I wrote them and then I moved a couple around because it felt better to do them in that order. My only recommendation is that you should listen to these songs in any order, but put The Walnut Falcon last because it’s really lo-fi and probably alienating.

Smith & Jones Forever

I had this friend who, after we graduated high school, traveled the world and then came back to the states with awkward white guy dreadlocks. I think he got them in New Zealand. It was kind of funny, and if you asked him now I’m sure he’d be like “oh, haha, those embarrassing dreadlocks,” but at the time I was sort of jealous of the way he was living his life, seemingly unencumbered by societal judgment. Not that I wanted dreadlocks or anything. No offense to white guys with dreadlocks, but you don’t really want to be a white guy with dreadlocks. I’m trying to think of an instance where it’d be a good look, and I’m coming up blank.

Anyway, we lost touch for a while, then reconnected when he moved to New York, coincidentally right around the corner from the shitty black mold-encrusted ground floor apartment in South Williamsburg I was living in at the time. The dreadlocks were gone, and he’d traded his obsession with Raekwon’s Only Built for Cuban Linx for an obsession with the entirety of the Silver Jews album American Water, which he loudly but reasonably claimed was not only the best Silver Jews album, but also the best thing David Berman made. A zonked-out indie Americana bummer classic. The whole thing is great, but Smith & Jones Forever is an obvious highlight – with Berman deadpanning a story about, I assume, the Depression-era American West. It’s bleak – trousers are being held up with extension cords, shoes are made of duct tape. The song ends with an execution via electric chair, but Smith & Jones don’t fade into the vast expanse of nothingness that comes with death, instead “something is added to the air.” They live on. No lesson is learned, but there’s a bunch sitting right there.

The last time I listened to this song with my formerly-dreadlocked friend was one of the last times we hung out (he’s still alive. He just moved and we lost touch. No big deal. It happens a lot when you get older). You could still buy Four Loko back then. He drank like two-and-a-half in a single sitting, stood up in an alarmingly lucid way, and then crashed through his glass coffee table. He was okay. It felt like I was witnessing Berman’s version of America.

Punks in the Beerlight

I didn’t know what to do with this song when I first heard it. It was an anthem, yeah, but it was also awkward and dark (the sentiment “I love you TO THE MAX” sits right next to lyrics about smoking gel off Fentanyl patches). Was this song embarrassing or amazing? The early-20s version of me could not figure out what to do with the layered approach to songwriting, so I just listened to it on constant repeat, puzzling over how it made me feel. Now that I’m pushing 40, I feel like I get this song: the exhaustion of hard living, speaking about personal trauma at a distance, putting big emotional gestures right next to beer-soaked moaning. At one point, Berman engages in a call and response with his then wife Cassie, who sings "If it gets really really bad, if it ever gets really really bad…" trailing off as Berman comes in with a defeated response: "Let's not kid ourselves, it gets really really bad." His voice dipping so low on “bad.” It’s a revelatory moment: hitting bottom doesn’t have to sound like hitting bottom, it just has to sound real.

People

And we’re back to another one from American Water. This time Berman’s writing about the fucked up give and take of nostalgia better than anyone out there: “I love to see a rainbow from a garden hose lit up like the blood of a centerfold. I love the city and the city rain. Suburban kids with biblical names. People ask people to watch their scotch. People send people up to the moon. When they return, well, there isn't much. People be careful not to crest too soon."

The Walnut Falcon

This is from the lo-fi early Silver Jews days – Berman’s voice buried under blown out guitars and cheap microphone fuzz. At one point in this song, it sounds like a door or a chair or something is creaking. The guitar stumbles over itself and Berman’s signature deadpan is more emotive and a little bit naive, but you can hear where he’s going to go. There was a time in life when I’d say that music this rough was for completists only, but now Berman is gone and we’ve got what we’ve got. There’s gems to be found even in the roughest material.

Margaritas at the Mall

It is still bonkers to me that my friends in the great band Woods made this perfect song on a perfect record with Berman – just a real all-timer record made by a bunch of brilliant musicians. It felt like the beginning of something, and then Berman died and it was over and the lone Purple Mountains album got turned into a sort of totem of death – one of those records that was great before but takes on a whole new heft after the main guy dies. Margaritas at the Mall was the first single from the album, and it’s one of the best things on there (I feel like All My Happiness is Gone has lately become the consensus favorite. It’s great for a lot of the reasons Margaritas is great, but I still come back to this one.)

The thing about this song is it’s Berman distilled: getting drunk in a garish mall, watching the world go by, everything tinged with neon-lit melancholy – “Magenta, orange, acid green, Peacock blue and burgundy” – but also the fact that it is so quintessentially Berman makes it hard to listen to now. How could we hear lyrics like, “Drawn up all my findings, and I warn you they are candid. My every day begins with reminders I've been stranded on this planet where I've landed beneath this gray as granite sky. A place I wake up blushing like I'm ashamed to be alive” and not realize what he was telling us? Not realize what was coming. Songwriting isn’t always 100% true, sure, but also, there’s always some deep truth embedded in every song. How could there not be?

Sam Hockley-Smith is a writer and editor based in Los Angeles. He helps make Victory Journal, an annual magazine that is basically a coffee table book, reviews books about music for The Southwest Review, writes occasionally for the few publications that are still going, runs a sporadically updated newsletter called Gross Life, and hosts a monthly radio show for Dublab.

Mike Young and Gion Davis

If Christ had died in a hallway we might pray to hallways

or wear little golden hallways around our necks.

How can it still be unwarmed after so many passings?

An outdoors that is somehow indoors.

- If There Was a Book About This Hallway

David Berman, among both poets and musicians, holds a prayer card kind of space. A saintly and mythical one. A totemic presence. A strung out Jesus standing in the hallway of our hearts in his sunglasses, fishing for his keys in his jacket pocket. He shows up on the bumper of your friend’s car as a sticker that says “Honk if you’re lonely tonight!” He arrives in the empty bar during a set that the DJ seems to be playing only for himself, spinning Tanglewood Numbers songs between reggae. He fails to appear in the digital jukebox where Caroline types in “Silver Jews” and then “The Silver Jews” to no avail.

He sings “And why am I drawn to you tonight?” while you sit in the parking lot outside the grocery store in your rural hometown, waiting for an ex-boyfriend to tap on your window, startling you, forever unrecognizable and familiar at the same time. David dies while you are trapped in the bathroom at the grotty punk house you lived in the summer after you graduated from the same MFA program he went to because he went there and then you are in the hallway beside him with everyone else who loved him, waiting for him to walk up the stairs, past the tangled bicycles of your hearts and knowing he won’t.

1. Punks In The Beerlight

How can you not love this song? If you’ve ever been a punk, if you’ve ever loved someone, if you’ve ever been a burnout, if you’ve ever stood in the pale, ugly light outside the bar drunk and shouting you love someone to the max. Berman invokes French art nouveau painter Toulouse-Lautrec, who painted barflies and lonely drunks wilting on their chairs in the bar light. Beerlight. He also painted posters advertising cabarets and people hungover in bed in the mornings. Punks In The Beerlight is the opening song on Tanglewood Numbers which, like Lautrec, democratically washes over all aspects of nightlife (and begrudging daylife) of being a musician and poet amongst other musician poets.

2. Smith & Jones Forever

David Berman was always looking for the footnotes instead of the paragraph. In Smith & Jones Forever, we are introduced to a wild west story song that is as much a love song as it is about outlaws, even though as it goes on, we realize it’s just about people living in drugs and poverty being seen as criminals. “Are you honest when no one’s lookin? Can you summon honey from a telephone?” are incredible lines to start a song with by themselves but they are also questions that ask us if we are good at the rules of society rather than are we worthy to live simply for being alive, which is also called into question in Random Rules immediately before it on American Water. Being a socially “good” person versus being a person deserving of care regardless of who they are and what they do is core to American Water and all of Berman’s work.

3. Sleeping Is the Only Love

I love this song and its definitions. It is one of the best versions of Berman’s sound, the simple and crashing drums, the smooth steady bass, the bell-like guitars ringing through and arcing up like a song you’d hear in a sweet movie about being in love. And the lyrics are dark and strange like his voice but tender too, like waking up from a bad dream into a warm soft morning beside someone you love.

4. The Silver Pageant

It’s so easy to get caught up in Berman’s lyrics that I think many of us often neglect his arrangements and his instrumental tracks. The Silver Pageant starts out with a recording of a party where people cheer and laugh and speak. You can’t really hear any specific words even as the party continues alongside the instrumentals. The song itself is jazz-adjacent, smooth and insistent with the instruments coming in one by one the way people enter a party. The party noise filters in and out, almost like a chorus or lyrics. As my friend Caroline Rayner (the preeminent DCB scholar of my life) said “the party sounds and voices work like lyrics to me and speak to a kind of like, random and inconsequential but extremely poignant joy and just like, delight in being together that speaks to David Berman’s poetic generosity.”

5. Self-Portrait at 28

Is it cheating to use one of his poems? Does that count? We can’t talk about Berman without talking about the poetry. After all, he was a poet first right? Self-Portrait at 28 is probably one of his longest (that we know about). It sprawls and moves in a way a song cannot. It is a portrait of a life but also a world that is slipping through the speaker’s hands. A world becoming unrecognizable in the way it does when you reach the end of your 20s. Berman writes

I can’t remember being born

and no one else can remember it either

even the doctor who I met years later

at a cocktail party.

It’s one of the little disappointments

that makes you think about getting away…

And that’s the crux of it all, the little disappointments and heartaches and also joys and victories and how they weigh against each other. It was the constant question he was asking in all of his work, one that we now are charged with answering.

Mike Young and Gion Davis perform in the band Clementine Was Right. Listen to their recent singles There Are No More Almond Trees or Takes Tall Walks.

Donald Borenstein

"Oh sure, this will be easy," I told myself. "I'm sure I can just fire these off," not knowing I'd spend an evening cutting this down from a top 25, most of which at some point I had in a version of my top 5. This list flows like the tides, because there is a Joos song or Berman poem that has been there for me at nearly every emotional inflection point of my adult life. After Luke jokingly asked me "not to make it 6000 words" after the Stop Making Sense piece I wrote for Hell World I... promptly wrote 3000 almost involuntarily. So I threw that out and kept this "short." Nothing I write can come close to doing his work justice, songs that mean more to me at this point in my life than those of likely any other artist. My thoughts will be clunky at best, accordingly, so forgive me - when it comes to Berman, the line between criticism and diary dissolved for me a long time ago.

5. How to Rent a Room

The Natural Bridge is my favorite SJ record, and it opens with a gorgeous, elliptical diss track (almost certainly against his father) that is among the earlier of many, many lyrical jousts with The End that would find their way into Berman's couplets. "You're a tower without a bell. You're a negative wishing well" is as cutting as insults get, but the part that always sticks with me is "Read the metro section (3x). See my name."

4. Smith & Jones Forever

Berman's lyrics are often described as inscrutably indirect (an assessment I disagree with for a lot of reasons), but Smith & Jones is as descriptive and evocative for me as any short narrative song, even if it trades in clear plot beats for moments in our two characters lives, engaged with as foggily as memory itself. It is a tribute to the joyful, rudderless friendship of degenerate youth, bumbling through the ecstasy and indignity of life with even fewer dollars than undamaged brain cells. "When they turn on the chair something's added to the air forever" is maybe the single best line Berman ever wrote, an accolade I don't use lightly.

3. Punks in the Beerlight

"Let's not kid ourselves - it gets really, really bad." The national anthem for dropping out of life for a little bit, Punks in the Beerlight is the kind of inverted love song that I gravitate towards the most – a pained, honest missive from the brink, driven forward by an undefeatable profession of love that, well, almost was defeated. It's about as close as there is to a real barn-burner in the Joos' catalog, ending in a loud cataclysm that makes the most of the robust lineup they had for Tanglewood Numbers.

- Dallas