Another villain who's taking all our money

Usually Hell World is a political newsletter, and sometimes it is a music site, and sometimes, as with today's two-parter, it is both. For paid subscribers we have a talk between the great labor and metal writer Kim Kelly and Maha Shami of the D.C. hardcore band NØ MAN about her new record and being the child of Palestinian refugees. You can jump directly to that piece here or read it down below.

"I’m Palestinian and a woman so not surprisingly challenging oppression and fighting for our right to exist are repeating themes," Shami said of their new record Glitter and Spit. "Recently I’ve been more mindful of the importance of radical love, both in my personal relationships at the community level. Meaning, how do we love one another fully without boundaries or strings attached? Conditional treatment doesn’t really show up until you’ve poked the bear and you’re confronting the status quo. It happens to women in punk protecting their scenes and calling out abusers. It’s happening now when folks preach equality and remain silently complicit during a genocide. Glitter and Spit is about not letting someone dehumanize you by distorting your reality to fit their fantasy."

Here's a 7 day free trial if you're not able to support Hell World with a subscription at this time.

Previously Kim wrote for Hell World about her Last Normal Day before covid, and we talked here about why cops do not belong in the labor movement and the leftist case for arming ourselves.

We also chatted about my Lockdown book for Teen Vogue a couple years ago.

Now let's talk about music streaming payments.

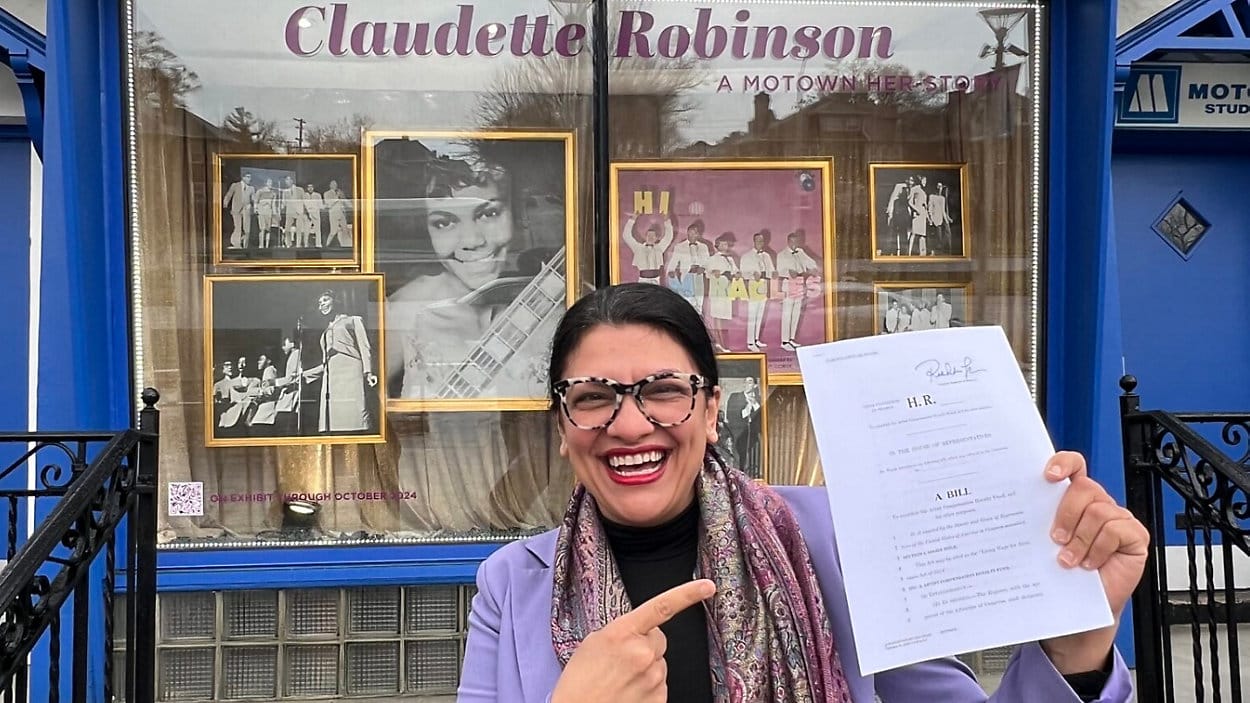

Earlier this month Representatives Rashida Tlaib and Jamaal Bowman introduced the Living Wage for Musicians Act.

“Streaming has changed the music industry, but it’s leaving countless artists struggling to make ends meet behind,” Tlaib said. “It’s only right that the people who create the music we love get their fair share, so that they can thrive, not just survive.”

Crafted in cooperation with the United Musicians and Allied Workers group, the bill hopes to increase payments to musicians up to one cent per stream (right now Spotify pays around $.003). The new money would be drawn from an increase in subscription prices, which might sound like a pain in the ass for users, but in this case that increase would be pooled into an Artist Compensation Royalty Fund and distributed back to the artists themselves, instead of how usual price increases go which is that some rich asshole just takes it. There would also be a 10% levy on streaming companies' non-subscription revenue and caps would be placed on how much an individual track can earn from these set aside funds to ensure that it isn't all going to the superstar musicians who are already earning most of the streaming money.

None of this is meant to replace the way streaming royalties are currently paid, but instead to be an add-on.

“There is a lot of talk in the industry about how to ‘fix’ streaming – but the streaming platforms and major labels have already had their say for more than a decade, and they have failed musicians," UMAW organizer and musician Damon Krukowski, a long time strident critic of the industry said. "The Living Wage for Musicians Act presents a new, artist-centered solution to make streaming work for the many and not just the few. We need to return value to recordings by injecting more money into the system, and we need to pay artists and musicians directly for streaming their work."

I called up Zack Nestel-Patt, a musician and UMAW member, and Henderson Cole, an entertainment lawyer who helped work on the bill (and also the founder of the fine music site The Alterative) to talk about how it all came together, and how the bill will benefit working musicians.

If you like you can sign the petition for the bill here.

Tell me about how you came to be involved with UMAW, and what led to this legislation.

Nestel-Patt: As you know, musicians are always on tour, and when suddenly we were all not on tour with the pandemic, we had time and bandwidth to meet on Zooms and talk about a lot of our gripes and complaints, and the noticed injustices of the industry were the topic of our conversations. We were all out of work, making no money from streaming. It was pretty dark. Collectively talking, and pointing fingers, and realizing we were all sort of pointing at the same thing, we decided maybe we should try to do something about it. So we started this organization.

The first campaign was to get government subsidies for musicians as small business owners, which was successful. Obviously without touring, and with the onslaught of the pandemic ruining our only recourse for income, it became very apparent, not that we didn't know, but the felt effects of the wildly incongruous money we were getting from streaming felt very real in a way that felt like we should tackle it as the main priority. So we started the Justice at Spotify campaign. We focused on Spotify because they are the biggest and the baddest. They represent a hugely outsized portion of the industry and really control much of what's going on. And that was wildly successful. We had, I think now, close to 40,000 people who signed on. We held a day of action in front of 15 Spotify offices around the world where we delivered our demands and held a rally. I think it changed the conversation about focusing on artists and demanding more pay and more pay equity. I think it hopefully opened some minds to the fact that Spotify is not the savior of the industry like they’ve really billed themselves, but rather yet another great villain who's just taking all our money.

At the end of the Justice at Spotify campaign we were talking about what we could do to really effect change. What is our equivalence of Fight for 15? The very materially focused immediate action that we can do to change what's coming into our pockets. Through extended conversations with experts, and really smart people like Henderson, we landed on this legislation, which wants to bring more money directly to artists by bypassing everyone else. Here we are.

Henderson, you're an entertainment lawyer, if I recall correctly.

Cole: My main thing is that I'm a music lawyer and an entertainment lawyer doing contracts for all different artists and stuff like that. But then on the side, it's always kind of been, along with doing some music writing and stuff like that, it's also been working on streaming and different ideas for streaming royalties and projects like that. Kind of cooking up some schemes, how to help these artists that I'm representing, but through actual changes in how the U.S. government pays streaming. So that's where I kind of got wrapped in with this.

I had been a supporter of UMAW, but then once I found out that they were working on streaming royalty changes, I started talking with them, joining in meetings and kind of cooking up how this was going to work and how it would actually benefit artists. Because just raising the royalty rate a lot, we found, if it doesn't get to the right places, it doesn't really benefit us.

If it goes from 0.003 cents a stream to 0.004, it’s not really going to do much, right?

Cole: Yeah, exactly. And not even just that, but if it goes through the same record contracts that have already dictated all this and ends up in the hands of labels or whoever has bought your masters in the years in between, that's another problem. So that's where we got to this specific legislation. It was really crafting something that would actually end up in the hands of artists. I think that's also why it's been able to actually get to Congress so quickly. People saw that this will actually maybe work, you know?

How did it make its way to Bowman and Tlaib? How did they get involved?

Nestel-Patt: We started working on this maybe like two years ago, which feels insane to say. But we started essentially just knocking on congressional doors, being like, hey, we've got this issue. Do you want to help us try to find a fix? And Tlaib’s team got back to us and said, yeah, this is an important issue. You know, I think coming from Detroit, Motown, a pretty serious history of music being made and the artist being exploited, she felt that this was something that hit really close to a lot of her constituents. The beauty of this is, most music lobbying is like Nashville, LA, New York City, but musicians live everywhere. One of the things we were able to do successfully in talking to congresspeople was, you know, Asheville, North Carolina and Memphis, Tennessee, all these places have vibrant musical communities and congresspeople, and we can talk to them and that's sort of how our relationship started.

Let's talk about some of the major points that this bill wants to remedy. I understand it plans to bring rates up to something like a penny a stream. And again, when you say that, that sounds like a huge victory, but still we're talking about a penny a stream! It just goes to show how bad these streaming numbers are already. So tell me a little bit about what the meat of the thing is.

Nestel-Patt: The meat of the thing is really just that. It just creates more money and gives it to artists.

Cole: I think the key aspect of it is that it would charge an additional amount on top of whatever somebody pays to subscribe to a streaming service, your monthly subscription fee. And make sure that that money, instead of just being an increase in Spotify raising their rates, which we know is already gonna happen, but will just end up in the hands of Spotify, we would say this increase goes directly to the creators of this track. It goes around the whole label system and it would be delivered – we don't know exactly by who yet, but very similar to the SoundExchange system, if not through that system – directly to whoever created that track. What makes it key, is that even if it's only a penny per stream, if we can make sure that at least a third of that penny ends up in the actual band account, that's a lot more than we would expect out of a penny per stream under the current system.

That's really the key of the whole bill. And then added into it there, since it's only based on U.S. streaming, since that's the only thing we can affect at this point at least, is that after a certain amount of streams each month you would be capped out. The goal of that was that after a million streams in a month, we're mostly dealing with very large artists who don't particularly need this bonus royalty as much, and if we can cap out some of those bigger tracks that's what allows us to get a higher royalty for everyone else. That was a lot of the time that we spent, and still are spending, on how to know how much money we could collect and how much money we could pay out and where it would end up. Because the accounting on this is ridiculous. Even being a lawyer, and even working with the musician union, it's a lot. We think that if we can make this happen it would be delivered directly to the artist. Even if it's only a little bit of money per stream it would still make a big difference in a lot of lives I think.

Is that cap on on big artists just for this specific allotment of new money?

Nestel-Patt: It’s just for the new monies that we create through this mechanism. It should be said that one of the things that we decided really early on was that this is not going to touch anything that exists in music law copyright ownership contracts. This doesn't affect anything else that happens in an artist relationship in their life. This is like a brand new thing on top of everything else

So Beyonce and Taylor Swift are gonna still be doing okay if this goes through?

Cole: I mean they would get a raise too, it's just that they might not get as much on some of the biggest tracks that are making way more money, but they would still get a raise too. I think it would benefit everyone. And that's where we've gotten support already on this from artists that are small and then artists that are huge too. And even labels and other people in the music industry, and that's what we've been telling the congresspeople is like, if you give an artist an extra $10,000 a year, they're going to spend most of that money on music, video people, or their management, or equipment. It's not just going to sit. They're going to put that right back into the economy. So I think it encourages everyone involved.

Right. It's like when they run these experiments where they give people, you know, a thousand people in a city, a certain amount of money a month. And then it always turns out they go ahead and spend that money, and they circulate it back into the local economy as opposed to when you're giving money to rich people, they just sit on it and hoard it. I do like that idea that smaller bands, maybe they'll be able to pay for a van that they couldn't before, they'll get back on the road, or maybe they'll be able to go into a nicer studio than they could afford before.

Nestel-Patt: Exactly. In our pitch to labels, I spoke with a number of labels to try to get them on board early, it was essentially that. It was like, you know, right now, a lot of your artists are hampered by lack of access to funds, and even though your main job as the label is to do artist development, there's a limit to how much you can give an artist. I think a lot of labels are like, oh, yeah, that fourth music video they could do, or that tour that they should probably take, but we couldn’t front, they’ll be able to go do. Or to pay for the mastering engineer or the extra week to just take time off from their jobs to write the next record.

Also, and this is, I think, one of the most important things for me, is that more money into the industry, specifically targeted to people who are not runaway superstar successes, means more diverse music being made and more diverse people making music. There's a lot of generational wealth in the music industry because it's extremely expensive to make music and tour and not have income and play the tours that lose you money, and spend $10,000 on a record out of your own pocket. These are things that real people and bands are doing. And that means that some people are pushed out of the industry or can’t access the industry. I think putting a bunch more money into that sort of grassroots level of music makers means that more people will be able to do that, and they will look more diverse, and they'll make more diverse music, because they don't have to pander to the playlists of some Spotify editorial intern or whatever.

It really sounds like it's about, and I think it’s something we'd all agree on, is that that the working musician class has been really decimated in the past 10 or 20 years, whatever it is. There's always going to be DIY scrappy bands, there's always going to be superstars, but it feels like that there's a whole strata in there that's been knocked on its ass lately.

Nestel-Patt: Exactly. I think that is the exact target of this bill, and the exact constituents of UMAW, this organization built by and for working class musicians.

So what are the next steps? Where do things go from here?

Cole: Right now we're talking to more people, and spreading the word about this among artists, because a lot of people honestly didn't believe that even getting this far was possible. Like, affecting real change and changing royalties in a major way. But it is possible, and we've gotten this far, and now it's about getting big support both within the music industry and also among music fans, and then bringing that to congresspeople and getting more of them on this bill. Senators are especially important. There are a lot more supporters of this bill than we even expected among both parties. And even though the sponsors of this bill are Democrats, that doesn't mean that there aren't Republicans who are ready to support it. It's just, we have to gain that momentum first, because we're dealing with an election year coming up, and it's gonna depend on who's in office in 2025.

Nestel-Patt: In some of our conversations, specifically with Darrell Issa's office, this is a Republican who does a lot on IP protection, we pitched him on this idea, and his legislative director, she said, you know, we heard from local church groups who were selling CDs, and being able to invest in their church, and now with streaming, they can't do that anymore. And we're like, yeah, that's exactly it. Like a local community who has music to invest in the community shouldn't pay for that.

What can people who are hearing about this for the first time do?

Nestel-Patt: I think the easiest thing is to sign your name on as support. And write a letter. On our website we have an easy way to do that, where you can automatically send letters to your congressional members.

Cole: And one thing too that we found is that this is one of the issues that hasn't become like a left versus right issue. Even Donald Trump brags about passing the Music Modernization Act during his time. So it's one issue that even if you live in a Republican district or a Democrat one, if you approach them about it, they mostly are receptive. There's nobody who really hates music, or very few people, I think. So we've been able to just approach people and say this will benefit your district. And people don't think like, oh, is this right wing bill? Is this the left wing bill? It's just about music.

Well, I have no doubt that if it starts getting more attention, they'll figure out a way to make it, you know, sound like a “woke bill” or something like that. But hopefully you won't get to that.

Nestle-Platt: The biggest pushback I'm sure will be about burdening consumers with this amount, which I do understand. I definitely feel that as a consumer who doesn't like my prices going up. Our pitch to this is that's already the plan. The major labels and the digital service providers have literally said they're planning on raising subscription rates. We're just saying wouldn't you rather that go to artists who need it, who you like, rather than the CEOs of Universal and Apple? As a consumer, that's very clear. If during the streaming TV and film strikes I were able to add on a portion of my payment to help people who are working in the industry to reach a minimum wage and living wage I would happily do that. And I hope people feel the same.

For sure. Personally I use Spotify, and I feel badly about it, but I wish there was a way that I could do it and actually support the artists. I think a lot of people don't mind paying a little bit more if it's going to the people making the art, instead of these executives who aren't doing anything.

Nestle-Platt: It’s been nice to see. I was expecting a lot more pushback on consumers paying the amount that goes to artists. I was really happy to see that people were generally like, yeah, if we get to support artists I’m down. I would love to support working class musicians.

Cole: One of the main reasons why we went with this specific structure was because around the world there's all different structures to benefit artists, a lot more than in the United States. Canada has a funding program where they give artists money that's very famous. South Korea has a huge program. Even countries like Spain and France, they make sure that a portion of streaming goes to the artists or goes to the collective government music agency. But in the United States, it's really a Wild West. We're not going to try and rewrite the whole book. The U.S. has this streaming law that allows them to dictate royalties pretty much. And people in the United States like to stream music. That's pretty much where we're at, you know, we're not going to be able to put that back in the bottle. So it's like okay, how do we find a way to use this system to get money in the hands of artists, and through the formulation that we found – and we worked with Harvard students and Harvard law professors and stuff – and they found that... You know when they sold blank CDs, Luke, which you will remember, there was an added tax on that to pay creators, because they were like these blank CDs will be refilled with music. Through the precedent of that, the government has had these systems before that said a new technology has come around, we need to make sure this money goes back to artists. That's really the basis of the bill. And just using that system and the streaming system that the government already has, I think this is pretty much the best we can come up with, at least at the moment.

It’s time that bands stop being afraid

by Kim Kelly

When Maha Shami sat down to write the lyrics for her band’s third full-length record, Glitter and Spit, she had no way of knowing that it would be released amidst the violence and suffering of yet another U.S.-backed war – or that the rockets’ glare would be illuminating the destruction of her own homeland. The NØ MAN frontperson is the daughter of Palestinian refugees, and her artistic output is deeply informed by the ongoing cycle of systemic violence that stalks her family members with every breath. Like many marginalized people, she found comfort and community in punk and hardcore, and NØ MAN sees Shami collaborating with Matt Michel (guitar/vocals), Pat Broderick (drums) and Kevin Lamiell (bass), all of whom played together in the groundbreaking screamo band Majority Rule from 1996 to 2004.

After a successful string of Majority Rule reunion shows in 2017, it became clear to everyone involved that it would be a shame to waste all that renewed creative energy. It was time to start something new – and Shami, who had guested on Majority Rule’s final album, was the perfect person to join them. NØ MAN formed later that year, and immediately hurtled into the fray with a burst of furious modern hardcore.

Now, three records in, NØ MAN has zero interest in pulling punches – and Maha Shami has a lot to fucking say. If the acerbic “Can’t Kill Us All” is the album’s mission statement, each track on the album offers its own spin on melodic hardcore catharsis, and they’re all fucking lethal. Shami’s vocals erupt from her throat like a stream of volcanic fire, her every syllable a warning and a curse. Offstage, she is measured, passionate, and honest; hardcore may define her life in D.C., but Palestine is home, and she is fiercely devoted to the cause of freedom. Read our interview with her below, and catch NØ MAN on tour in May.

Kim Kelly: Your new album, Glitter and Spit is coming out at the end of the month; these songs were obviously written well before the current conflict, but it may as well have been made for this moment. What was running through your head as you were writing these songs, and how does it feel to be performing them live now?