An abundance of everything except for one single thing

A terrible thing is happening to you now

Ah crap my perceived in-group status didn't shield me from fascism. I was really counting on that.

I know this might come as a shock to you but The New York Times Editorial Board has published a bad piece about where the Democrats went wrong in 2024. Can you possibly guess what they think a major part of it was?

Second, Democrats should recognize that the party moved too far left on social issues after Barack Obama left office in 2017. The old video clips of Ms. Harris that the Trump campaign gleefully replayed last year — on decriminalizing the border and government-funded gender-transition surgery for prisoners — highlighted the problem. Yes, she tried to abandon these stances before the election, but she never spoke forthrightly to voters and acknowledged she had changed her position.

Even today, the party remains too focused on personal identity and on Americans’ differences — by race, gender, sexuality and religion — rather than our shared values. On these issues, progressives sometimes adopt a scolding, censorious posture.

What shared values exactly? Literally what is a shared value we all have as Americans that they expected Democrats to focus on if not acceptance of our differences? Uh... Going to the store? Fuckin...

Do you ever ask yourself why the Times is like this? Well I will tell you why it is because they are all Republicans.

Why are the elected Democrats always like this too you might also ask? You’re never gonna believe this...

A big part of why the elite media have been railing against the supposed power of the purple haired baristas with their frivolous concerns and moralistic hectoring for years now is the older and middle aged writers' struggle to reconcile the fact that – while they do actually have considerable power of their own – the lefty students protesting against war and for trans rights and so on have something that they will never have again which is youth.

There is an abundance of everything available to every human being on earth except for one single thing. And running out of it can drive a person insane.

To be fair it's driving me insane too but it is pushing my soul in the opposite direction. Life is supposed to be beautiful and everyone should get to live it without a gun – metaphorical or literal – pointed at their heads every second of every day.

I wrote something on this theme a while back:

What I'm saying is that there is a very long and storied tradition of trying to explain away young people's natural and instinctive horror at war and racism and segregation – and our desire to commiserate and organize collectively against them – as a fleeting and unserious dalliance of youth to make the adult warmongers and racists feel less bad about the faint tug of conscience they're struck by from time to time.

When some amoral loser tells you the kids are being brainwashed by TikTok into opposing genocide in Gaza they're basically some guy from decades ago blaming civil rights protests on the hula-hoop or whatever.

The contemporary liberal will say today retroactively that the civil rights protests were righteous of course because unlike then they have nothing at stake right now. Just like they will say the same thing about protests against Israel down the line. Sooner or later when they find the humanity they've tucked away somewhere deep in their hearts because they convinced themselves it was a silly thing – or too heavy a thing – to carry around every day.

Some related reading:

One of many moments in Omar El Akkad’s new book, “One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This,” that will stop you in your tracks.

— Andrew Simon (@simongandrew.bsky.social) 2025-03-29T20:31:52.375Z

A terrible thing is happening to you now.

The Washington Post had one of these interchangeable smug assholes take a few swipes at the left as well.

I don't know a single "left leaning" or even centrist person who were relieved Trump's reelection would let them share their "real thoughts" on trans people and race. It sounds like maybe you just hang out with awful people. www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/202...

— tom mckay (@catturd2.bsky.social) 2025-03-29T20:55:56.692Z

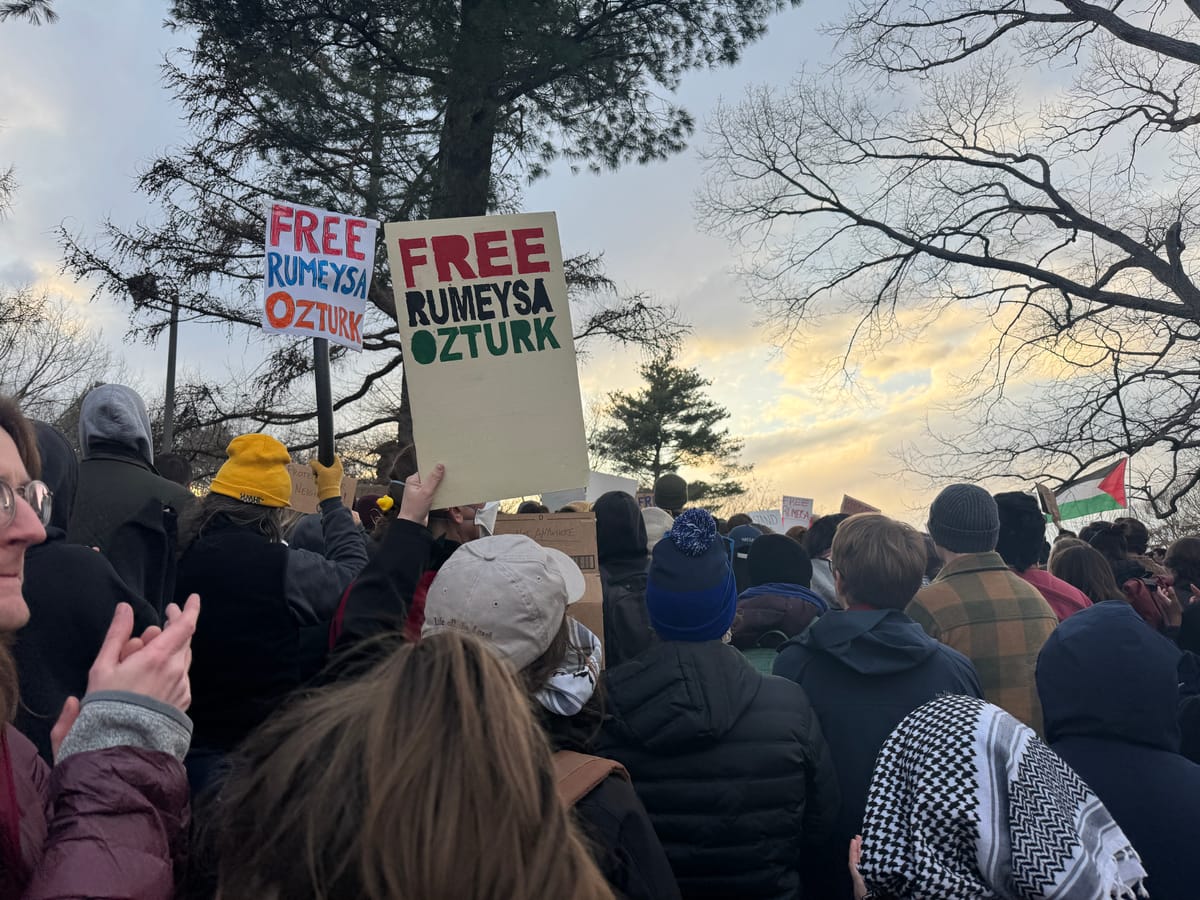

it's been years upon years of labored "campus culture" op-eds from salaried writers hectoring students about free speech, and now the state is kidnapping students for their speech in broad daylight

— JP (@jpbrammer.bsky.social) 2025-03-26T20:00:11.053Z

I'm holding two contrasting thoughts in my brain at once every second I'm awake and most when I'm asleep which are:

1) It is truly over.

2) They're too sloppy and too arrogant and it will not stand.

Which one do you reckon it is?

Did you miss this one the other day? A good one in my opinion.

I asked people in here last week to write in about what they are doing to stay sane or to fight back or build community or whatever else. Let's read a bunch of their responses below.

Chip in if you can to keep this hunk of junk floating. Here's a nice discount:

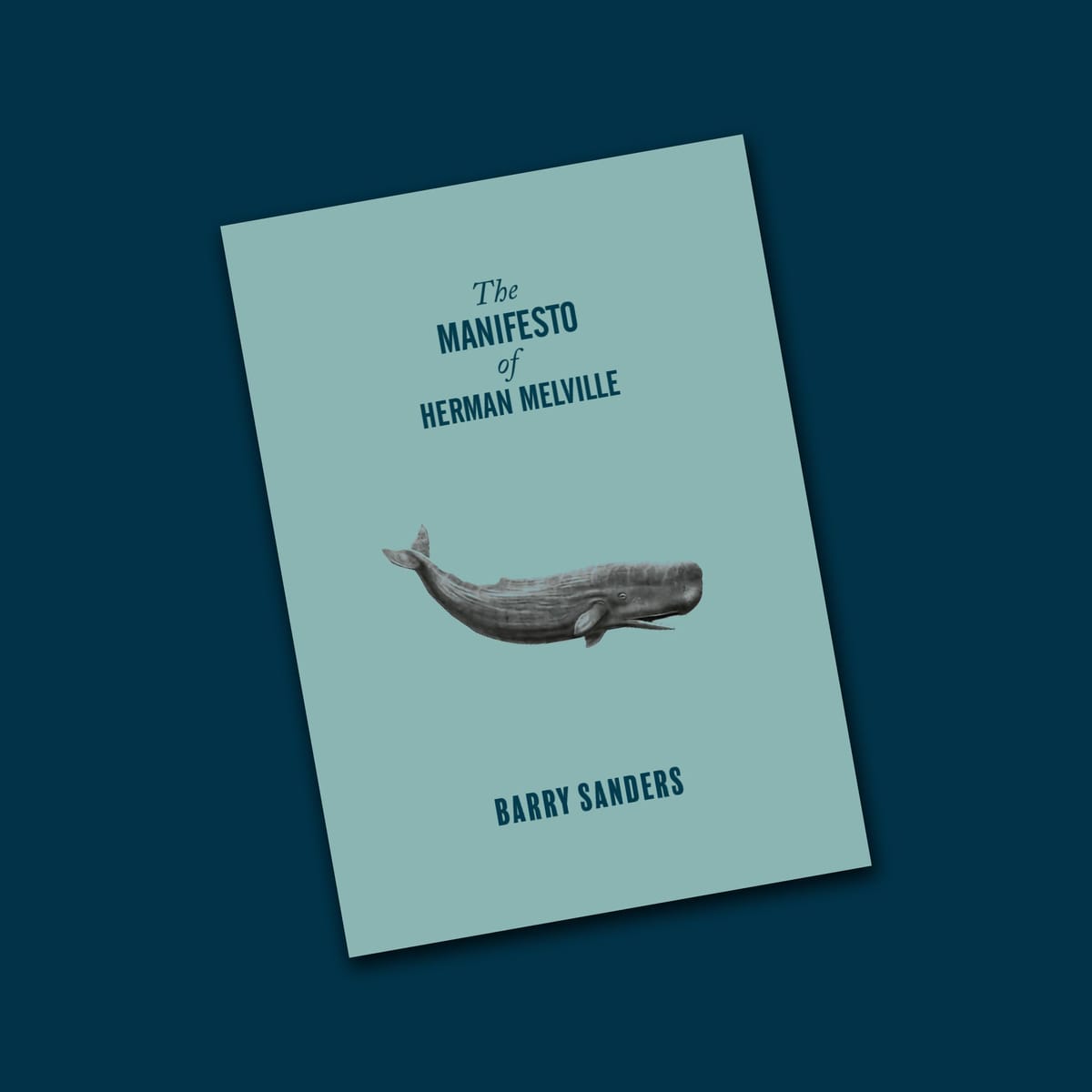

Before we get to that you might also check out this excerpt from the forthcoming The Manifesto of Herman Melville by Barry Sanders (not that one) that I'm honored to publish. Read it here or down below. (It's available for pre-order via OR Books). Sanders is the founding co-chair at the Oregon Institute for Creative Research-E4, a two time finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and the author of fourteen books.

"Moby Dick does not so much require reading as it demands tolerance—for the way it disorients readers and provokes them into reflecting," Sanders writes. "Moby Dick does not require readers as much as it demands thinkers and activists, those who can hear and overhear with a certain clarity. Which is to say, it aims for a slowed-down, contemplative rumination on the sorry state of nature, the crooked hearts that took it down, and an extrapolation into what might pass for a future."

"Moby Dick is America’s first manifesto, a tocsin sounded to warn us about the encroaching end of nature," OR explains. In the book he "argues that Moby Dick needs to be recognized as Melville's manifesto: a bold statement warning of the destruction of the natural world."

the Dunkin’ logo has never felt more accurate

— Tim Barnes (@timbarnes.bsky.social) 2025-03-29T16:06:37.267Z

In somewhat more heartening news the Great Grandpa album is finally out and it is gorgeous and pushes itself to places few other bands would think of to take these arrangements.

I wrote a bunch about them in my best songs of 2024 piece.

Here are some reader responses to "how it is now." Feel free to write in or comment below with one of your own. Surprising amount of divorce going on in here. Maybe not all that surprising actually.

I'm choosing to fight back hard and also, possibly, leave the country. I can do both at once, since leaving the country is a long process, and while I'm still here, I will fight. I am nonbinary so I am afraid for my safety, and the safety of people I love in my community. I've renewed my passport but could not change my gender marker to "X" because then I'd be denied a passport, which is straight-up oppression. Same with my partner's situation. I've been telling other people what's happening, like the deportations, the destruction of due process, the denial of passports to trans people, etc, since the news coverage is abysmal. Information is critical right now, so I've been reading a lot, mostly Timothy Snyder, so that I can educate myself about how this specific brand of fascism works and where it comes from. Information and education help to fight back more effectively. And while I'm here, I fight. I am planning to protest. I will try to flee if things get truly bad. After so many brutal years of American politics, I simply want a life of peace and if I can find it, I will take it and help as best I can from a safe country.

Sorry to hear you aren’t doing well, and I am right there with you. Depression and anxiety symptoms are really ramping up for me. People keep telling me that little actions matter, and to act locally, but I can’t help but feel insufficient.

So how am I keeping sane? Pretty sure I’m not. Fighting back? I yell into my Senators’ voicemails. Donate and subscribe when I can. Probably going to my first Tesla protest on 3/29. Building community? I try to stay in touch with people who agree with me. But we all have jobs and kids and are already full up on responsibilities. It’s hard to do much more in life.

Thank you for this newsletter. It always makes my day a little better to read a Hell World.

I moved to a region of the country I generally can’t stand and wanted no part of in the first place, but my wife was from here and she landed a really good gig, so we moved here three years ago — far, far away from my friends, family, favorite clubs to see bands at, and my team’s ballpark.

Well, that marriage fell apart. The signs were there all along but we trudged on hoping for progress that never came. Not a great course of action, it seems. If we didn’t have kids, I would have been on the literal first flight back to where I consider home to be. But we indeed do have kids, and I simply can’t/won't be away from them. So now I’m stuck in this place I don’t want to be, typing this from my Kirk Van Houten Divorced Dad apartment, where I’ll be living much, much leaner than I did when I was able to have my ex-wife’s six figure salary to tap into for groceries and such.

This is the perfect opportunity for my loneliness, resentment, and previously diagnosed depression to all go into ludicrous speed. In an effort to keep my mind and body from being stuck to my bed for days on end (I’ve had a few lately!), I’ve started volunteering at a food bank in the largest city near me on the weekends when I don't have the kids. It’s certainly early, but I can’t deny it’s already helping me a lot. From 8 am to noon on the last two Saturdays, I go to a part of the city so sad and broken down that it instantly reminds me just how delusional it is for me to ever complain about anything, and I help load cars with food, move boxes in/out of walk-in fridges, sweep floors, break down boxes, etc. The woman who runs the place is the kind of good-hearted person you always want to believe exists and you’re genuinely touched when you see one in real life. She looks very tired but she’s still polite and warm, and still trudges on helping people, regardless of the shortage of volunteers she has that week or what her budget has been slashed down to.

It makes me feel good knowing I’m taking a sad situation and turning it into something more positive, but I also have a part of my brain that won’t let me forget how easily I could have been doing this, literally, my entire life. I could have done infinitely more with it than the mindless shit I did do. But as part of my whole deal lately, I’m actively trying to maintain a more sympathetic inner dialogue with myself. “Yeah, you could have done more. For sure. But you’re doing something now and that’s all that should matter. Be kinder to yourself, you moron. And don’t get so upset at the lady who is taking selfies while she puts carrots and cabbage into brown paper bags for people.” (Oh yeah, that’s a thing. Did she come to help people or did she just come to SHOW people/internet strangers she came? I can’t think about it too much.)

I wish I was back home. I wish many other things were different. But they aren’t, and the first step in helping me make the best of the situation is realizing I’m in complete control of how this whole part of my life is going to go. I come from a long line of lazy men who didn’t get the life they thought they deserved so they became bitter and petulant toward everyone while letting jealousy completely replace their own ambition. And I see how it happens! But that’s not me. I’m not going out like that (thanks, B-Real). I might not be able to change all the parts of my life I want, but I do know helping the most vulnerable people around me is a good first step in trying to make an unfamiliar place begin to feel something more like home.

Look up volunteer efforts in your area. There are so, so many, and there are such good people who are devoting their lives to this stuff. Those people who are actively putting tangible good back into their own communities deserve the help as much as the vulnerable people they’re helping. Plus, the opportunities tend to only be like four hours long. I assure you that you have four hours in your week where you could do something to help this awful place be better. And it will keep you from sitting at home and thinking the kind of thoughts you know nothing good comes from. Everyone wins, I swear.

PS: I’m not the praying type, but I’ll just say I’m hoping for the best for your sister and your whole family. Your readers read you because they connect with the emotions you put out into the world. So when you’re happy, we’re happy for you. When you get awful fucking news, we feel awful for you, too. We care and I hope she gets the kind of medical care on par with the love she’ll be surrounded by.

I have been distributing 100s of free COVID-19 tests to my community, mostly to co-ops/stores, protests, other people distributing and organizations helping houseless people.

I have been helping Massachusetts Coalition for Health Equity with two "Right to Mask" bills in Massachusetts. Essentially, banning mask bans (Mann, wer hätte das gedacht Dass es einmal soweit kommt).

Bill S.1427 - An Act prohibiting municipal bans of face coverings for protective or medical use: https://malegislature.gov/Bills/194/SD245

Bill H.1981 - An Act relative to the right to wear personal protective medical equipment: https://malegislature.gov/Bills/194/HD2968

I'm supporting Willie Burnley Jr. running for mayor of Somerville against some very obviously real estate people: https://www.willieforsomerville.com/

I keep telling myself, fascists and the complacent cannot do anything worse to me they haven't already done, which I've already survived. I have never been sane and don't think that's happening anytime soon. It is very important, at least to me right now, to be entirely true to myself and protect myself, thwarting bullshit which takes introspection and sacrifice. I can't help other people if I am a shitshow myself, you know, which is the point to all of this.

How I'm coping: hiding out in another country, writing inane blog posts, sending pics of hilarious bathroom graffiti to unsuspecting recipients.

As they say around here (and they say it a lot lately): ELBOWS UP!

How am I doing? Feeling mystified at how even people who care need to have a fire lit underneath them to get them to take actions, but heartened that some people have after I asked them to, and I am buoyed by meeting other people who are trying to do something.

Listening on repeat to protest songs, anti-fascist songs, especially the old gravelly voice versions. Viva la Quinta Brigada. Bella Ciao. Hasta Siempre Comandante. The Boys Are Back In Town.

Enjoying nature...the turtles are back in town. The buffleheads are leaving town (sad).

Subscribing to a lot more newsletters than I used to, and reading books on anti-fascist fighters in different countries…how they endured, how they failed, how they kept the fight alive even when the fight was over.

Went to a few events, and it was surprising to see the old folks both in numbers and up in arms. Pondering how to get people I know to take more actions, the ones who are upset. This is the hardest thing, especially as the people I know my age aren't in jobs that are easy to unionize or they're looking for a job. Feeling frustrated at people I know who aren't taking action and the ones who just don't seem to get that it really is this bad.

I felt a strange sense of peace last night, in between bouts of despair while reading a Jeff Sharlet book; the peace was a realization that I will never be these people, neither the Christian nationalists nor the tech weirdos, and also, we will all be dead at some point, and there is no way that their version of God is real. Whatever my faults and future sins, I won’t be lauding the prosperity gospel or AI hype. Sometimes it feels freeing, because they are fully masks off, there is no covering up the stench of their rot at this point. It's like finding a strawberry collapsed into mold versus the too-soft strawberry without visible mold adjacent to it. One you can throw right out, the other you might feel obligated to try and eat.

I really appreciate this newsletter and the work journalists who are not in exclusive Signal group chats are doing. Thank you.

UNIONS, heck yes!! I'm a card-carrying Wobbly partly because my local (which operates as a woefully understaffed service-model union, even though they like to pretend they're a w2w organizing-model union) consistently fumbles the bag on a lot of things. My union leadership acts more like an employer than like fellow workers. But a lot of us actual fellow workers are quietly doing as much as we can to hold each other up in the workplace, including coalition building with other unions and workers' groups. Organizing is intensive work, and can be dispiriting because it doesn't pay off in a short (or sometimes even medium) time scale, but it's abso.fuckin.lutely critically important, now more than ever, so I keep putting my nose back to that grindstone. Though it sounds like my fellow organizers and I need to start adding some fun and prosocial stuff to our agenda.

Coping mechanism: I bought a turntable and started a vinyl collection. For every hour spent doom-scrolling, I log a couple of albums worth of no-phone musical contemplation. It's expensive, but the mental levees are holding, for now. Motown is keeping me sane.

The only thing keeping me sane right now is I left social media and therefore direct my anger where it rightfully belongs (in the inboxes of my representatives/senators, where they get weekly reminders they're fucking cowards for picking and choosing which folks get to enjoy constitutional rights based on their skin color and appetite for genocide). I get as a writer with some followers, social media is kind of required, but a regular asshole like me is a six pack ring in the ocean and every second I spent searching for an island was another day I was bombarded with ads. Plus I just visited my folks and my mom showed my dad a fuckin nightmare Facebook video of a big band playing Another Brick in the Wall Pt 2 but the musicians were cocker spaniels; like something the gen alpha version of David Lynch would make if David Lynch sucked shit. She says she can only watch content like that because everything else on there is too depressing (like the actual news). God forbid she did what she used to do pre-social media, which was read actual books. Since I can't do anything to make her stop, the least I can do is give the smallest middle finger to the billionaire shitheads by actively not participating. Oh and finally getting divorced, can't recommend that enough if you don't love your spouse/partner. Like removing a ten ton weighted blanket you thought was grafted to your skeleton. Most days I'm lighter than air. Sorry to brag, man, especially when your elbow hurts. Helluva Severance finale, though right?

Warning of the destruction of the natural world

by Barry Sanders

Melville’s injunction is mighty, huge, and distended—perhaps even impossible. Every suggestion and solution to the devastation of the Earth must be oversized, fueled by the intensity of Ahab’s rage and the distortions of Melville’s prose, from Ishmael’s demands on us, to Moby Dick’s percussive power against the Pequod, from the length of the book to the overwhelming injunction to halt killing now. In our catastrophic epoch, we cannot back away from the impossible, for the end is closing in fast. To cap global warming at that 1.5 degrees C. over pre-industrial times, we must reduce greenhouse gas emissions 45 percent by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050.

Because life on Earth is under threat of extinction, we must radically reinterpret our spirit and destiny. Intent on stopping eco-murder, Melville Shanghaied the reader out to sea—a practice popular in the 1850s—to a new horizon and perspective, to witness the killing of the mighty and the majestic. Melville reveals his revulsion by situating the name of the whaler, the Pequod, within one of the country’s most shameless acts of killing. The Pequot people lived on territory that would become Connecticut. In 1636, a coalition of colonists who needed more land for their crops attacked the Pequot village, burning down their homes and killing over 700 people.

The Pequod departed Nantucket on Christmas Day, turning its back on the birth of Christ in favor of the death of whales, and listing dangerously from its heavy cargo of hatred and rage. When the Pequod sinks, so does an era and an attitude, providing Melville the chance to revitalize language and literature. Dispensing with the familiar in storytelling, along with acceptable sentence structure, grammar, and at times, logic, Melville abandoned style, making both the power of the Manifesto and the wonder of the natural world to come fully alive.

Melville underscored his experiment, perhaps in homage to those sonic wonders, the whales, with a literary trope called Voice. Whereas style can be conscripted from any period and imposed on prose, voice takes its life from reactions in the moment. For style to be effective, some crisis must prompt people to speak out loud. Something shockingly elusive, and even frightening forces that shout into being. Voice makes people brazen, prompting both immediacy and intimacy, resonance in a single word that describes speaking and writing, lungs and language: volume. Voice makes itself most apparent in our first cry for life, our tiny crowning or breaching, akin to some water-based mammal, forgoing the amniotic bath for fresh air, announcing our arrival: I am here, a power as yet uncontained. Take heed and, quick, call me something.

And because Voice, above all else, relies on breath and breathing—sentences, too, must come up for air—vowels over consonants, assonance over alliteration, pitch over persuasion, the elegiac over the meditative. Such an emphasis on breath, oddly enough, favors consonantal languages, like Phoenician, Hebrew, and Arabic, as opposed to, say, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, French, or even English. Consonantal languages can only be read aloud, breath a living substitute for vowels—vowel and its variants, vow and avowal, provoke and invoke, share a root in voice—and, like God breathing into clay and bringing Adam to life, the speaker’s breath animates the consonants, bringing inert characters to life as words, and then bringing words to life as characters.

Voice is the Sh’ma of literature, the idea that, to understand, one must push beyond the sometimes-listless act of listening, to the intensity of hearing. Voice is a lure, or maybe merely alluring, with its promise of intimacy. As we set sail, propelled by its booming shouts and epithets of hate, unsettling prose rhythms, and more, Moby Dick seems freighted with voice and perhaps even overwhelmed by it: Everyone and everything speaks, from the waves to the terns, from the whales to the wind, and even to the listless creaking of the Pequod’s keel: The world is alive. We have sailed into the past, into a time when nature spoke.

From every direction, there comes noise and notes of discord—gulls screeching in maddening circles, whales blowing air and water, and a crew shouting demands that negate prior demands. The water-logged vessel moves at the will of the wind; each greenhand demanding a witness; nobody and nothing there does not yearn to be heard. Killing aboard a whaler is deafening and chaotic, a messy and clumsy spree of killing, a victory over life, sounded in huzzas of horror, in days freed from the usual twelve-hours of wakefulness.

We meet the sentences of that New England brooder at the depth of full-fathom five, those grave lines of Herman Melville, in his unmuzzled state—far from any trace of Boston Brahmin aloofness—breaking the bonds and boundaries of literature. As albino, even the whale betrays logic. On deck of the Pequod, there are a parade of people of different colors and countries—thirty or more crew members building their own towering babble.

Voice is much more than mere speaking. Voice is the expression of Melville, not just as an author with the volume turned up, but as an authority pitched to the whale’s ear with a warning; and here, voice is Melville at his most direct. To hear him requires more than listening, something closer to sacred hearing from the bible—again, the Sh’ma of understanding. We must pay strict attention, learning anew how to comprehend the word, for Melville is in charge certainly as author, but much more as authority and seer.

And so, voice is Herman Melville’s way of declaiming what he knows, an outspoken loudmouth waking and warning his readers; and voice is Herman Melville, as a character staring directly back at us, whose truth echoes with manifest immediacy. Finally, with a voice pitched so high and so loud, Melville’s words linger and hover, making certain we read him correctly. Herman Melville has crafted his own language of knowing: A voice of insistence in the might of the Manifesto.

The Industrial Revolution was looming, and people felt the change of rhythm in their daily lives, in their stride, in their speaking, and the rapidity with which they made their choices and their purchases, transactions suddenly stripped bare of barter and banter, and eventually of money, itself–demanding a different way of seeing and thus knowing, a new rhythm of breathing, and a new vocabulary able to apture those new and radical dislocations.

People needed to be informed of change in so-called real time, which meant stripping events of their complexities and subtleties of interpretation. The ticker tape, new in the 1860s, allowed stock brokers to transact in real time—profit in an instant. A grand robbery was taking place, and the precious object, stolen in plain view, was nothing less than reality, itself. Once the old pace of life had been supplanted, it would prove impossible to retrieve it, for dynamos grew more powerful, revolved more rapidly and more loudly—with few or nobody wanting them to slow down. People took comfort in the new power and its purported dependability. By 1851, the word horse-power had lost its hyphen and its animal connections, so that the catalog for the Great Exhibition could refer to “an oscillating steam-engine of ten horsepower.” And people knew it meant something other, something more than ten horses pulling a wagon. Horsepower meant engine capacity, measured in cubic inches, power made audible in a new measurement called revolutions-per-minute, or RPMs.

The wreckage of the Pequod symbolizes the end of a world but also the beginning of a new and protracted time, one that dismantled and destroyed the familiar—an incredibly brittle period, in which trust got replaced by the new-fangled promise to revolutionize people’s lives into something remarkable through the mechanization of the everyday.

This was true—as incredible as it sounds—even of language, which towards the end of the nineteenth century developed new words, like train, revolver, pulley, telegraph, camera, and new psychological terms, like agoraphobia, along with the repulsive Negrophobia and, in 1856, a near epidemic of fear and nervousness labelled neurasthenia. Reacting to the proliferation of the neologism, and to the many changes in meaning of old ones, in 1857, board members of the Philological Society of London called for a new dictionary. Close to thirty years later, in 1884, lexicographers produced the first fascicle of the Oxford English Dictionary.

Herman Melville disrupted our entrance into the corrupting, highly industrialized, thoroughly mechanized, and consumptive age, and made us pay attention: Smack in front of us lingered the wreck of our ship of state, the tale of ruin told by someone near drowning, bobbing haplessly in the vastness of the Atlantic. Something has gone terribly wrong, beyond the odd and amusing. In the new industrial age, people had become orphaned, displaced, in need of being called a name and in need of a calling. They were certainly in need of knowing, for even narration turned out to be unreliable, shedding rational, reliable telling for a drowning sailor in Melville, an illiterate adolescent in Twain, a madman in Poe, a Transparent Eyeball in Emerson, a so-called idiot in Faulkner, and “the most terrific liar you ever saw,” Holden Caulfield. The word abnormal entered the language in 1835, appearing first in Richard Hoblyn’s Dictionary of Medical Terms. Only a few years after the swamping of the Pequod, harpoons continued to pierce deep into the flesh of whales, but in the new machine age, human effort was replaced by cannons mounted on the bow of the ship’s deck. Powered by black powder, and fitted with scopes, men fired harpoons with uncanny accuracy, over great distances, each round a guaranteed kill, for as the harpoon pierced the whale’s flesh, a grenade exploded— instantaneous death.

Leave the deck of the Pequod, enter the town and look around: Handiwork of every kind was being scrapped to make way for some new, alluring machine that carried out routine work much more quickly, accurately, efficiently, and most importantly, more cheaply and without complaint.

Wherever people seemed to wander in that accelerated world, they came up against something new, startling, and mechanized: the sewing machine, the telephone, the trolley, the camera, the typewriter, the train, the escalator, the elevator, the safety bicycle, the time clock, the revolver, and the Gatling gun. One might even spot a helicopter or an airship crossing the sky.

Not only were people encountering new machines almost everywhere they turned, but with the introduction of the automobile, they actually sat on or in a machine and assumed the controls themselves, becoming truly auto-mobile. By 1890, an oddity appeared at key intersections, called the stop sign, which instructed drivers to halt their machines for those outmoded pedestrians. On May 12, 1901, Connecticut placed a limit on speed, the first in the country—ten miles-per hour on city streets, and twelve on country roads. Just after the turn of the century, in 1901, Ransom Eli Olds, the son of a blacksmith, introduced his stylish creation, the Oldsmobile.

By design, Moby Dick cannot be read in a single sitting. To be effective, a Manifesto must both agitate and arrest readers, slowing them down more and more until they come to a full stop. Melville’s critique of impending horror must be read as a document of extreme urgency and insistence, a demand to protect all of creation and to pause, think, and then to act. Its title has been ceded, not to a person, but to a mammal, a whale that should not be named. The Manifesto must present reality in such stark terms that its demand for a change in attitude, and then in policy, seems not only reasonable but inevitable. First must come that critical change in people’s own attitudes and then in their own vision.

Literature could no longer disregard the state of the natural world, but it needed a new form. By shedding the traditional outlines of the novel, Melville reached a level of critical independence that was most effectively delivered in a statement of revolutionary intent and will. Melville revealed how gratuitous killing could result in the total erasure of the natural world. He insisted that we listen; he demanded that we pay attention. He cast his eye on society and refused to shed a tear, to acquiesce, or to turn away, for he was, himself, far too outraged, far too much in the know about the consequences of a population under the sway of some unhinged, power-hungry dictator, who he hoisted up the main mast for us to see in all his bellowing and bluster. No one who cares about sanity can suffer a distortion like Ahab. No one who cares about sentient life can tolerate such a madman, his unpredictable eccentricity, or his explosive, destructive willpower.

For Melville, conciliation and compromise are simply not acceptable. As he moved farther and farther away from the expectations of the novel, he sailed off into the uncharted territory of seared and, at times, scorched emotions, under the sometimes-terrifying demands of a version of capitalism rushing full-speed into the unknown, the uncharted. Singularly possessed, he ignored harsh reviews and dismal sales.

Moby Dick does not so much require reading as it demands tolerance—for the way it disorients readers and provokes them into reflecting. Moby Dick does not require readers as much as it demands thinkers and activists, those who can hear and overhear with a certain clarity. Which is to say, it aims for a slowed-down, contemplative rumination on the sorry state of nature, the crooked hearts that took it down, and an extrapolation into what might pass for a future.

For Melville, in its full-blown, nineteenth-century iteration, the novel had been exhausted. The drawing room, the boardroom, the bedroom, commanded interest no longer. Now, it was the natural world and our callous treatment of it that called for serious attention. Even Walden, a meditation on the glories of nature, written but a mile from Concord, was too much of a retreat from the realities of a ravished Earth.

The new regime, fascinated by mechanical speed, efficiency, and power, chose industrialization over ethics and the protection of the natural world. Melville knew it would be impossible for people to back off from such undoing of the rational: “There is no folly of the beast of the earth that is not infinitely outdone by the madness of men.” Such a magnified tale of terror and madness could only be told on that grand Oceanica, on a voyage, up close and in the heart of chaos, madness, and killing, far out of range of eye and ear, beyond the horizon of noticing, in a place without borders or measure—the expanse of the sea—in a ship that may seem calm, but aboard which holds a crew who comes dangerously, dispassionately alive through killing, which comes to port as commerce and cosmetics.

On the ocean, everything normal turns odd and amplified. One remains, continuously, in the middle of its vastness, inside its weather, shouting to be heard, gesticulating to be seen, taking risks just to be acknowledged as a living being. Life gets enlarged and distorted into a caricature of the real and the actual. In the rush to kill, in the rendering of flesh, and in the cult of cash, life gets diminished—for both the killed and the killer. Men rearrange the idea of life by removing the largest, most noble of its creatures. Whales are determined to stay alive; whalers are determined to snuff out their lives.

In the end, Herman Melville left the library for the lectern. What will he deliver, one wonders—perhaps a sermon? More pointedly, Herman Melville will deliver his warning to every last person, in Manifestos of deep concern, of lofty indignation, underscored by a thunderous NO. He insisted that we do more than hear his word and that, in the most highly charged sense, we overhear. In the newly invigorated and recalibrated world, one inspirited by people trying to hang on to their own sense of being against the rapid takeover by dynamos, dynamite, and derricks, it falls not on the politician, and certainly not on the scientist/engineer to act as the people’s seer and the Earth’s savior: It is the artist who sees most clearly.

We will come to our senses only through the insistence of someone like Herman Melville, who takes us back to an earlier time and makes us witnesses to the wonder of everything that is, just as it is. How much mightier, more powerful, and courageous can a creature become than a whale, who will eventually best his foe, survive harpoon wounds, escape yards of encircling, thick ropes, and defeat its killers.

The converted, contrite, and half-dead Ishmael, who has been wronged, wrung out, and finished by the interminable lust for killing and commerce, comes closer to acting as our guide, to narrating our own condition, than anyone even remotely resembling Ahab, blinded, crippled, and deranged as he is, and no longer by rage but, finally, by his misplaced hatred. For Ishmael, the telling of his tale must make him feel that nothing matters much but salt and water, and beyond that, only more salt and much more water. Not even on shaky ground, Ishmael rests on something far less substantial, and yet he is handing us Melville’s will and testament for the Earth, his Manifesto delivered to so-called survivors, while spinning his yarn—in the lingo of the sea, looming it—far from shore. For Melville, the deepest of seas may be the right place for his narrator, for as he put it: “Yes, as everyone knows, meditation and water are wedded together.”

Barry Sanders is the Founding Co-chair at the Oregon Institute for Creative Research-E4. He has twice been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and is the author of fourteen books and over fifty essays and articles, including Sudden Glory, Alienable Rights (winner of the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award; with Francis Adams), ABC (with Ivan Illich), The Private Death of Public Discourse, and A Is for Ox.