A refusal to participate

Say Nothing and a history of hunger strikes

Earlier this year I interviewed John Oakes about his fascinating and extremely well-researched book The Fast: The History, Science, and Philosophy of Doing Without. In part the book investigates hunger strikes as a tool of resistance in cultures throughout world history including in Ireland during The Troubles. Considering a recent episode of the very well done FX series Say Nothing deals with the hunger strike – and brutal force-feeding – of IRA member Dolours Price I asked Oakes if he'd adapt some of his research into a piece with that period in mind.

Please consider a paid or free subscription to this newsletter if you appreciate our work. Thank you for reading.

The River of Kings

by John Oakes

“Power depended upon public obedience, a will to submit.” — Vladimir Bukovsky, To Build a Castle (1978)

Sometimes an activist’s best weapon is a refusal to participate: a hunger strike. When applied in certain situations, the simple act of not eating becomes jiu-jitsu politics that inverts the power structure and can undermine authority more effectively than a bomb. The hunger striker signals that she has been pushed into a situation where she is not being heard, or is being heard and ignored. She may not control how those who claim authority treat her: but she can assert agency over her own body.

The principle is ever-present, and has an ancient, cross-cultural pedigree that seems part of the human psyche. When a more physically powerful adversary pushes us to extremes, we still retain a weapon within the tiny realm of our bodies. I was reminded of this recently when watching the series “Say Nothing,” featuring the historical figure Dolours Price, a volunteer for the IRA who was imprisoned by the British in the 1970s. Together with her sister Marian, Price went on a hunger strike for more than 200 days and endured 165 days of force-feeding.

At any one time, there are dozens, perhaps hundreds of people undertaking hunger strikes around the world. Many of these strikes go unremarked, but the fasts are a binding agent within the groups that undertake them. The line between fasting-as-protest and a hunger strike is largely one of semantics. A hunger strike draws on the language of labor movements to evoke a work stoppage, an action by community members. A fast suggests a moral goal. But in reality, there is little difference between the two. More than a protest against conditions or a call for attention, fasting in protest can express solidarity, and solidarity means trouble for the powerful.

At this moment, sixty-eight year old mathematician Laila Soueif is entering the third month of a hunger strike on behalf of her son Alaa Abd el-Fattah, held in an Egyptian jail for his writing. After a five-year sentence, he was due to be released this past September—and when he was not, his mother began her fast. “I am willing to go as far as it takes. I don’t think the Egyptian authorities react to anything unless there is a real crisis,” she told The Guardian.

In the 1970s in the Soviet Union, the dissident writer Vladimir Bukovsky was repeatedly imprisoned for public outrages such as unsanctioned poetry readings. Prison authorities were alternately infuriated and baffled by his actions—they knew they had to respond, but weren’t sure how to do so. Several times Bukovsky protested unreasonable prison strictures with hunger strikes, which never failed to upset officials, who then resorted to more brutality. “The authorities always turn savage when you back them into a corner,” he wrote in his memoir. “But that is precisely the moment to break their backs.” Eventually, Bukovsky’s stubborn determination to undertake hunger strikes became known throughout the Russian penal system. The Soviets resolved the problem by exiling Bukovsky, his mother, and his nephew to Switzerland.

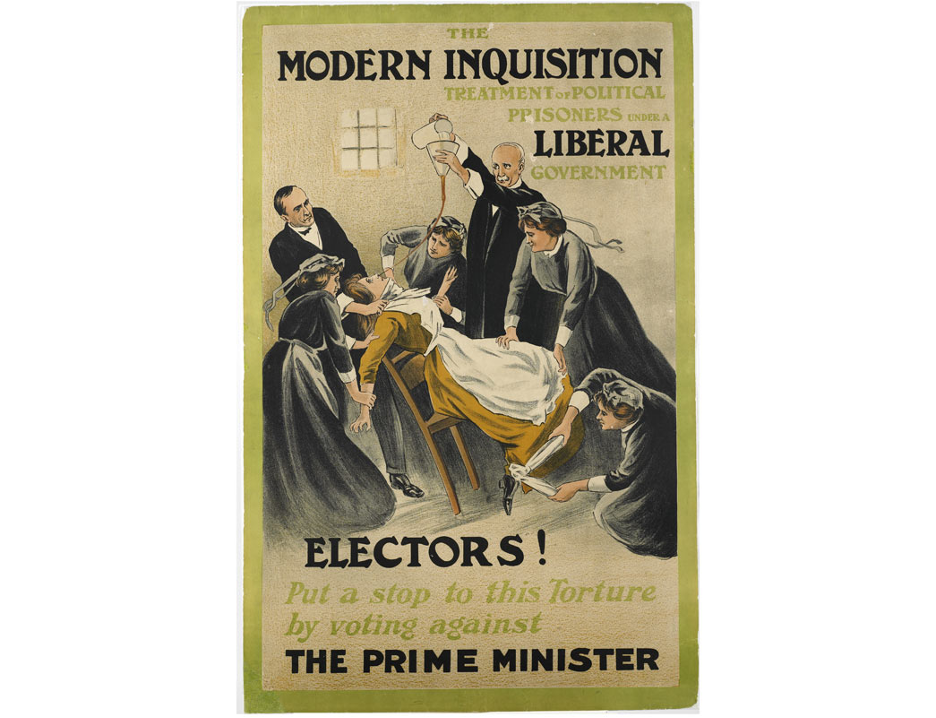

“Say Nothing” vividly depicts the horror of force-feeding. It may seem strange that a hunger strike often compels those in power to step in and try to stop it; a hunger strike is meant precisely to attract attention. But if prison authorities let a strike continue to its logical conclusion and rid themselves of an irritant, they cede control. To let a prisoner decide her own fate deprives the state of its object lesson.

Ironically, force-feeding was an innovation of the Enlightenment in late-eighteenth-century France. Philippe Pinel, a pioneering precursor of modern psychology, was the first to advocate force-feeding for mentally disturbed patients, arguing they needed sufficient nutrients to get well. At the time, the prevailing view was that the insane could not feel hunger and required little food. Then, a century later, German physician Adolf Kussmaul, after experimenting on a professional sword swallower, introduced the mercilessly direct antidote of the stomach tube. Asylum doctors quickly embraced the method as a way to curtail fasting and to break the resolve of their patients.

Force-feeding satisfies the requirements of any reasonable definition of torture. It can involve full-body restraints and an apparatus to force open the relevant orifice, a variant of the speculum oris, an instrument originally used by physicians and adapted by slavers to keep kidnapped Africans from starving themselves to death during the Middle Passage. If a tube is improperly inserted into the throat, food can enter the lungs, and suffocation or infection can result. Soft tissues can be damaged. Whatever the method employed, force-feeding requires utter physical subjugation of a prisoner. And yet it reinforces the impact of a hunger strike: the brutality proves the striker’s argument.

The River of Kings is a twelfth-century CE saga of the kings of Kashmir. Throughout the saga, the praiseworthy concept of prāya, fasting to the point of death, appears. In classical Sanskrit, prāya carries with it the connotation of a warrior’s action, of sallying forth to battle. While the act of fasting might seem at an opposite extreme to the behavior of a warrior, there is a recurring cultural link between the two: the yamabushi in Japan—famed for defeating samurai in single combat—and the sannyāsin in India—Hindu ascetics who developed martial arts—both valued extreme fasting. In the sixteenth century the sannyāsin fought the Mughals, and in the late eighteenth century, during the Sannyāsi Rebellion, they again rose up in opposition to the British East India Company. (They lost.) The routines of the Knights Templar, medieval Christian warriors, involved fasting on a regular basis. In biblical times, Jews fasted before going out to do battle with their enemies. For ancient warriors, fasting provided not only spiritual strength but martial vigor.

Prāya is normally cited in epic narratives as a means of coercing wrongdoers into correcting the error of their ways. That could include something as ordinary as refusing to acknowledge lingering debt, or a more serious crime against oneself, or a person in one’s own household. Self-harm or suicide from despair is a sin in Buddhism and Hinduism, disdained as a destructive act and “self-abandonment.” But as in Christian traditions, exceptions are made for holy men and women, ascetics, and martyrs.

In Ireland, the history of fasting in protest long pre-dates the arrival of Christianity on the island and is a powerful practice known as a troscead or cealachan that once had its own codified set of rules. Lawbreakers and in particular debtors were “fasted against” and would suffer the ignominy and supernatural peril of a hunger strike at their door. Crucially, fasting was only applied against a person in power, and involved a public shaming. As with the Indian institution of prāya, if the dispute continued, a kind of “stomach-duel” then ensued. If the debtor, whether chieftain or wealthy farmer, denied the claim, he was obligated also to take up a fast until he either offered food to his creditor and pledged to settle the debt or submitted to a third party’s ruling on the matter. According to the fifth century CE Senchus Mór, or “Great Book of Irish Law,” fasting was seen as evidence of moral rectitude. A failure to fast was not only anti-social; it revealed moral depravity. Fasting was so highly regarded and revered as a kind of mystic weapon that “fasting illegally” merited a fine.

When Christianity swept the island in the first part of the fifth century, obliterating almost every trace of druidic rites, the troscead remained and was elevated in status. Fasting was essential to early Christianity as evidence of ascetic commitment to the religion’s principles, and fasting’s centrality in Irish culture undoubtedly facilitated the conversion of the Celts. Fasting—and in particular fasting as a tool for change—was closely associated with no less an authority than St. Patrick himself. At the age of twenty-three, kidnapped from Wales by Irish pirates even before he had begun to proselytize, the saint claimed to have heard a voice praising him for his fasting. Tírechán, an Irish bishop writing in the seventh century, reported that the saint fasted for forty days while “being assaulted by large birds” on the summit of what is now Croagh Patrick.

In the modern era, the first to use a hunger strike as a political tool in Ireland was the English voting rights activist Elizabeth “Lizzie” Barker, who had come to Dublin to disrupt the 1912 visit of Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. (During his visit, Asquith narrowly missed having his head split open by a hatchet thrown by suffragist Mary Leigh.) Barker was freed within days after declaring her fast. From that point on, the hunger strike became an essential tool in the arsenal of Irish rebels, both women and men.

The Irish Volunteers, a paramilitary organization formed in 1913, revived the tradition of fasting-in-protest in the name of Irish independence. The Volunteers fully expected to be arrested and sentenced. One of their principles was “to hold drill parades in public in the presence” of the Royal Irish Constabulary, and when sentenced “to go on hunger strike for political prisoner status.” Between 1913 and 1923, approximately ten thousand Irish prisoners went on hunger strike.

A grim turning point both for Irish independence and for the role of the hunger strike came the following year, when Thomas Ashe, a thirty-five year old Dublin school principal, was arrested along with thirty-nine members of the Volunteers. Ashe, a founding member of the Volunteers and a participant in the Easter Rebellion, was imprisoned for a speech he had made. Charged with “attempting to cause disaffection among the general population,” he went on a hunger strike, demanding to be tried as a political prisoner or released. After a week of force-feeding, Ashe collapsed. He died within five hours of his hospitalization. His death in Dublin’s Mountjoy Prison on September 25, 1917 was barely noted outside Ireland, but three thousand uniformed members of the Irish Volunteers turned out to accompany the funeral procession and “tens of thousands” of mourners lined the streets. The revolutionary leader Michael Collins delivered the funeral oration, and Irish newspapers emphasized Ashe’s “strength and brute masculinity” to highlight force-feeding’s cruelty. The effect was to lead sympathizers to conclude that since Ashe was neither suicidal nor particularly vulnerable, the system had murdered him. With Ashe’s death, the prisoners arrested with him were released, and force-feeding was temporarily suspended. While hunger strikers didn’t need to die to be effective, their deaths amplified their message: as Yeats wrote in The King’s Threshold, “the man that dies has the chief part in the story.”

After Ashe and until the death of ten members of the IRA in 1981, the most notorious self-sacrifice in Ireland was that of the Lord Mayor of Cork, Terence MacSwiney, who died in October 1920. MacSwiney’s acceptance speech when he became mayor in April of the same year, shortly after the assassination of his predecessor, embodies the hunger striker ethos: “This contest of ours is not on our side a rivalry of vengeance but one of endurance—it is not they who can inflict the most but those who can endure the most who will conquer.” Arrested at Cork’s City Hall while presiding over a court of arbitration, MacSwiney was charged with sedition and sentenced to two years in prison. He died on the seventy-fourth day of a hunger strike. MacSwiney’s death by self-starvation was the first to be widely reported on outside Ireland, and inspired worldwide sympathy for the Irish cause, notably on the part of Gandhi. Also paying close attention to the news of MacSwiney was a certain Vietnamese immigrant to England—a dishwasher at the Carlton Hotel in London, who later changed his name to Ho Chi Minh. “A nation which has such citizens will never surrender,” he is reported to have written upon hearing of MacSwiney’s death.

As the unionists maintained their hold over Northern Ireland through voting restrictions and gerrymandering, and as police refused to protect peacefully protesting Catholics, tensions increased. By the early 1970s, close to a thousand prisoners were held without trial under the Special Powers Act at Long Kesh Detention Centre, a former airbase outside Belfast better known as The Maze or H-Blocks. A turning point came when British soldiers attacked a non-violent demonstration on January 30, 1972, resulting in a massacre of fourteen unarmed civilians that came to be known as “Bloody Sunday.” A hunger strike later that year resulted in IRA prisoners gaining “special category” status, giving them the right to be treated as political prisoners in everything but name. When special category status was withdrawn in 1976, an upsurge in hunger strikes occurred, culminating in the strikes of 1980-81.

At the time, the British government was well aware of the dangers that hunger strikers posed to its standing with the public. The British secretary of state for Northern Ireland had earlier warned Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher that a hunger strike was “a ruthlessly determined act.” The government needed to loudly proclaim its own determination, and so a few weeks later, Thatcher told a radio interviewer that “if these people continue with their hunger strike, it will have no effect whatsoever. It will just take their own lives, for which I will be profoundly sorry, because I think it’s a ridiculous thing to do.” On December 18, the first strike “ended in failure,” according to former IRA member Pat Sheehan, with the authorities conceding nothing. At the time I spoke with him, Sheehan was a Sinn Féin representative for Belfast West in the Irish Parliament, but in 1980 he was imprisoned along with a number of Irish fighters, among them Bobby Sands, then 27 years old.

As “Officer Commanding” of the IRA members being held in The Maze, Sands declared a second hunger strike over the objections of other IRA prisoners. The hunger strike and the subsequent death of Sands on May 5, 1981, after sixty-six days of fasting, brought worldwide recognition to the prisoners’ protests. Nine other strikers died around the same time, but it was the death of Sands that resonated. It became a kind of “post-mortem ventriloquism (literally: speaking out of their stomachs),” as one scholar put it. Were the prisoners suicidal? After all, a number of imprisoned Irish rebels had starved to death in relative obscurity (or achieved only local notoriety). Pat Sheehan reacted emphatically to the suggestion. “We were healthy young men, with life ahead of us,” he told me. “It was never our intention to die.”

In October 1988, the British government banned interviews on state-regulated media with not only the IRA but with its legal political wing, Sinn Féin. The government said it wanted to deny them the “oxygen of publicity.” What authorities gained in terms of order, however, they lost in terms of credibility, as human rights organizations, free speech advocates, and opposition politicians—many of whom disagreed with the Irish republicans—objected to the heavy-handed measures.

Adapted from The Fast: The History, Science, and Philosophy of Doing Without