A little ghost for the offering

The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman by Niko Stratis

I'll tell you one thing I'm going to do – and it's no small thing right now – and that's continue to stand with and hold up trans people and specifically support trans writers. And fuck you if you're not doing that too.

Today we have an excerpt from the forthcoming book The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman by Niko Stratis which you can and should pre-order!

It's something of a memoir in songs in which Stratis details her journey from a working class life as a closeted transwoman in the Yukon Territory to becoming the person and writer she is today with the help of Dad Rock favorites like Wilco, The Replacements, Bruce Springsteen, Radiohead, The National, Songs: Ohia and many more. Of course when I saw that there was a chapter about R.E.M. I figured I pretty much had to choose that one. Especially since Niko previously wrote about her 5 favorite songs by the band in this piece.

Speaking of Dad Rock maybe you missed this beautiful piece by Rax King from the other day on the passing of Garth Hudson of The Band.

I had four new short pieces go up at Flaming Hydra the other day. Here's one people really seem to like. Paid Hell World subscribers can read another down below and the others here.

The rules

I was fighting fascism with the power of love and kindness and just really getting my ass handed to me. A total bloodbath. The referee would have stepped in by now but they had knocked him out with a steel chair. The only others watching were either fascists themselves or the people trying to fight fascism with the power of love and kindness and they weren’t having a great go of it either. I kept trying to explain in between haymakers that we were better than this and on top of that it wasn’t likely to be ruled on favorably as far as the courts. None of it helped. I was on my knees now bleeding profusely from the mouth and nose. It spilled out of me onto the snow in a pattern that if you sort of squinted at it just so from the right vantage looked like a heart. See that I pointed. Look how beautiful the world can be I tried to say through my broken teeth. Alright well now he was pulling out a gun. I didn’t think we were allowed do that.

Since we're talking music today I finally somehow stumbled across an interview I did with Noel Gallagher all the way back in 2002 that I mentioned in this Hell World about the best of Oasis. God I must have been excited about that. Young shithead that I was who didn't know a single thing. I'll throw it down below for paid subscribers to read. He was obviously very funny.

Here's Niko introducing the chapter and the book:

The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman was a title before it was a book. When I wrote it down, it spoke to me in ways I wouldn’t fully understand until I worked through it. I know there will be issues with what I claim as Dad Rock, because we hold onto precious things with delicate care and it’s easy to imagine any label as a pejorative, but I use Dad Rock with love. I chose these bands and these songs because they saved me, and they tether me to memories that I had to make peace with to survive. It’s an exploration of transness hidden away in the Yukon, but it’s also about labour, death, loss, love, and awkward triumph and I think this chapter on “Man On The Moon” speaks to that.

Excerpted from The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman by Niko Stratis out May 6, 2025.

See you in heaven if you make the list

Man on the Moon - R.E.M.

In late June 1982 in a hospital in British Columbia, a nurse washed my newborn body in a basin under running water. She was, I’m certain, a lovely and kind and caring woman who loved her job most days but probably not all days, and I imagine every now and then she circled listings in the classifieds and wondered if she should get back into retail. Some days being a nurse must be exhausting and draining, and you do what you can to get through the work. Our days are not always perfect; we survive by learning to balance difficult memories with cherished ones.

The day I was born might have been a hard day. Whatever happened, she was there but not fully present in her work, and when she was cleaning me the water—meant to wash my newly delivered body in her hands—was running directly onto my face, covering my mouth and my nose and my eyes that had only just seen fluorescent lights and tile floors for the first time. I was drowning, and she was absent in attention while my mother fought exhaustion to raise her voice loud enough to say that I was looking a little blue.

Memories linger with open-ended questions. Maybe this is just my anxiety speaking, but I am preoccupied with all the what-ifs and maybes left behind as I age deeper into adulthood. This is an idea that floats to the surface of “Drive,” the opening song and central thesis for R.E.M.’s 1992 masterwork Automatic for the People, an album exploring nostalgia, trauma, loss, and moving forward all at once. An album about youth as it transitions to adulthood and what it means to carry the past with you into the future. Stories and half-truths that define a life. Lessons passed back from those who have managed to survive into the future of this world.

I don’t remember everything, and this is the most damning thing you can say in a collection of words rebuilding your own past. Some of it just isn’t there anymore. Some memories that were once a clear picture are faded images on a page, turned ashen grey with time. Some memories are just told back to me by those who only half remember ever being there themselves. Some memories are just stories to tell.

Evan Dando said it perfectly: “I’ve never been too good with names, but I remember faces.” A woman I dated in 2002 in Alberta who drove a Jetta and was obsessed with the burned CD she had with a bootleg of the first Maroon 5 album, a guy I worked with for eight months on a high-rise building, my supervisor who was divorced and wore the same sweater every single day. I remember them, but only just, their outlines and textures. Blurry faces and voices dancing in the wind of my mind. I remember how it hurt to be dumped over text by the woman with the Jetta. I remember that supervisor showing me how to play Golden Tee at a dive bar after we left the site early because of a bomb threat.

I didn’t die when that nurse nearly drowned me in a hospital in British Columbia, but water imprinted on me that day all the same, marked me with the terror of its sinister promise, and a phobia grew in me like an unchecked weed. I have always been afraid of the water, and I have always been afraid to die, and I have always been drawn to both.

When I was a kid, my mom would bathe me in the yellow and amber plaster tub in the old bathroom of my childhood home, and I would freak out every single time. Sitting in the water was fine, but when she washed my hair and the water had to run down my head and over my face, I would respond with cacophonous panic, screaming loud enough to shake the gold and yellow and brown tiles on the wall.

The neighbors called the cops more than once; they were worried something unspeakable and terrible was hiding in the darkness of our home, and it took a few times for all parties to learn that this was just what bath time was going to be like for a while. Eventually my mom got me a little shield, a green plastic and foam visor that stopped water from going over my face, and it helped bath time become something close to bearable, or at least quieter.

I don’t remember any of this, but I’ve been told the stories, and the truth of stories told doesn’t always matter as much as the dots they might connect to bridge lives together.

R.E.M. is a band of memories strung into a lifeline. Formed in 1980 in Athens Georgia, by Bill Berry (drums), Peter Buck (guitar), Mike Mills (bass), and Michael Stipe (vocals), R.E.M. is the progenitor of what we would start to classify as alternative rock. Everything needs a label, a genre, a category. How to classify that which doesn’t work in the mainstream, until the point that it does.

In the 1980s R.E.M. didn’t easily fit onto commercial streams, but they were rising steadily in popularity all the same. How do you define something that is beloved but markedly different?

R.E.M. was already popular by the time they entered my life. “Losing My Religion,” from 1991’s Out of Time, was in steady rotation on radio stations and MuchMusic. I loved them because Kurt Cobain loved them; he talked about them in magazines alongside bands like the Pixies as important to his own growth, and I was just the right age to absorb everything he passed on like a sacred truth. The prevailing rumor is that when he killed himself in a garden shed in 1995, he was listening to Automatic for the People. I bought a copy to help decipher the clues left behind in his wake. This was the last thing he wanted to hear before he left this world—what secrets are held in here?

I don’t remember being kicked out of swimming lessons as a child, but I know it happened. I know I stalled out at earning my blue badge, when you had to be able to put your head under the water with your eyes open, at the old Lions Pool down on Fourth Avenue right next to the High Country Inn. The rub was that you weren’t allowed to wear goggles, and I simply couldn’t do it. I was being tested on how adept I was at managing my trauma and I failed. I became good at failing but not always good at managing it.

My mom protested to the swimming instructor that I should be allowed to move on, that I had put my whole head under water but just kept my goggles on. “That isn’t good enough” is all she was told. I had to do it the same as everyone else or I couldn’t move on—find and follow the mainstream. My mom was told I would never get past the point I was frozen in and that she should just take me out of class. Give up on swimming. There was no getting better than this.

R.E.M. initially wanted to make a heavier record after the release of Out of Time, a mostly somber and soft record that found the band moving from cult favorite status to undeniable popularity driven by the success of “Losing My Religion.” I would imagine it’s hard to know where to go after you achieve success previously thought unattainable. How to hold on to your voice knowing that more people than ever will hear it? It was Peter Buck who suggested they explore something a bit more reflective and slowed down. With all eyes on them, they turned pensive, pulled out mandolins and pianos, and burrowed into their origins. Trading in influences of the past and looking at the struggle of young lives as they turn old.

Automatic for the People is a masterwork of lush arrangements, alluring chords and rhythms that lay a foundation for Stipe’s voice to build mazes of indecipherable poetry upon. A record of secrets, dead ends, and doubling back. Spend your life within its walls and you may never unlock all of its tightly held secrets. What is clear from the outset, as “Drive” comes slowly into focus, is that we are here to grapple with the weight of getting older. We must make peace with loss and trauma and difficult memories we can’t shake. “Drive” is both first communion and last rites, the sound of a tether between worlds. Leave youth behind but remember all the scars it leaves on the body.

For many years after I failed swimming lessons, I refused to go anywhere near a pool. I never liked being underwater, didn’t like how the water clung to my skin and held tight on my anxieties. I didn’t like the sensation of water, and I didn’t like the feeling of being exposed to the world. I also did not like the changing room.

Men change in the men’s changing room.

I didn’t like my body, a slow-rolling stone gathering far too much moss. I never went back to the public swimming pool, but there was a hot spring just outside of the city with an arcade in the lobby that had the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles game where four people could play at once, and that was enough to get me close to my greatest fear. To go into the pool, you had to first go into the changing room.

Men changed in there without any sense of fear or shame. Chests laid bare, asses and dicks hanging out for all to see. All shapes and sizes, hard angles and soft lines. As a young teenager I was growing and changing, shifting in my body and seeing the new limits it would find for itself. I’m told the first time I ever went into the changing room at the hot springs I cried and refused to get out of the bathroom stall. This, too, is a memory I don’t have; it’s just a story, the tale of a life half remembered.

R.E.M.’s lyrics have never traded in clarity at the best of times, and on Automatic for the People they only became more inscrutable. Michael Stipe’s poetic twists and turns of phrase are not here to lead us down a well-worn path. Rather, he invites the listener to sift through and find answers where you need them.

Automatic leaves itself intentionally vague. Where “Drive” is the central thesis of the record, it’s “Man on the Moon” that holds it together. On the surface a loving ode to deceased comedian Andy Kaufman, it’s a song that fills the void between choruses with references to the Game of Life, Mott the Hoople, and the horrible asp that plagued Egypt (it’s widely rumored that Cleopatra committed suicide by sneaking a venomous asp into her chambers in a basket of figs and letting it bite her). Stipe, in an interview, stated that the repeated use of “yeah yeah yeah yeah” is because he was delighted at how often Cobain used the word yeah in Nirvana songs and wanted to see if he could outdo him in a single track.

There were rumors, always rumors, about Michael Stipe’s sexuality. In 1994 he became the subject of endless sexual discourse that sought to make sense of him, this gaunt and striking figure who stood at odds with so much of what we expected a man in a rock band to be. There were no sharp edges or blunt corners to his form, every bit of the maze of questions found in his work. He wore a hat with the words “White House stop AIDS” in the midst of the ongoing AIDS crisis, and this, too, led people to ask questions as they did about any man who made public declarations of solidarity with those fighting a disease primarily afflicting LGBTQ+ people. There are always questions, and often they are not asked in good faith. Every time people wondered about Stipe, it made me wonder, and it made me lose myself in his work that much more. What secrets might be hidden there in his work?

“Man on the Moon” draws on the death of Kaufman as its central theme and with it looks at the world of possibility Kaufman chose to create around himself. That in all the darkness and unknowable dangers of a life, there is something magical to be found if we let ourselves look for it. Ask questions; there are always questions. Don’t always accept the answer. Believe the lies that may help you make peace with what might otherwise be a life of endless torment.

In high school, one afternoon when the sun was too hot and the air was too dry, my friends and I craved respite from the brief months of endless sun in the Yukon summer. We drove up the road that trailed off through the cliffs behind my house, up another winding road darting around the cliffs and walking trails, then down to the clearings by the river where day camps and picnic tables were set up. I pulled my 1988 Datsun Maxima into a day camp site, opened the doors, and let punk rock mixtapes drown out bird songs and the sound of the river. We drank cheap beers and wine coolers stolen from older siblings’ and parents’ hiding places and found a world in which to survive.

The Yukon is often dark, often cold, isolated and removed from the world and plagued by the dangers lurking in banality. There’s not often a whole lot to do other than develop habits that will come to haunt you in later years. But some days, like this one in the summertime, we could drive out to the water and pretend everything was always going to be just like this forever.

Andy Kaufman never wanted his story to be fully told. This is what we’re led to believe as Jim Carrey method acts his way through his life in Man on the Moon, a movie titled after the R.E.M. song, which also appears on the film’s soundtrack alongside “The Great Beyond,” a song R.E.M. wrote for the film that attempts to honor a life of devilish half-truths and secrets to tell. Kaufman delighted in subverting truth and reality in life, subterfuge that followed him into death as rumors persist that he faked even that last and final act. Stipe sings about the impossible task of writing about a life that was never about the end, only ever about the thrill of the journey.

I’m pushing an elephant up the stairs.

At the pullout where we drank and drowned out our voices with punk rock records, there was a tire swing that swung out over the cold water of the Yukon River. This afternoon in the early summer, everyone took a turn swinging out over the water and jumping in. Everyone but me. Everyone but me and the anxious fears that plagued me. The endless tears and failure of my childhood that created this lifelong fear of going under the water. My friends were in the water, floating and laughing and chanting and calling for me to jump in. I couldn’t tell them I was terrified of dying in the water like this.

R.E.M. worked on Automatic for the People in pieces. Peter Buck, Mike Mills, and Bill Berry created instrumental beds, and Michael Stipe came in after to populate the universe they had conjured with lives and love and loss and all the beautiful things that build the memory of a life. Lyrics were written in a panic as recording was winding down and Stipe just needed something, anything, that felt real. He couldn’t arrive at the answer. Writer’s block set in. The death of the artist. Days before the album needed to be finished, there were no words to fill in the blanks on what would be the second single from the album.

I took my glasses off out there in the campground by the river, my fear of water and death smothered just a little in stolen beer and skunk weed. Without glasses I am unable to see anything; the world becomes shapes and blotches, splatters of meaningless color. I heard the chants of my name and I couldn’t respond with my fears. Instead, I walked out to the tire swing. Held onto the rope to test its strength. Took my clothes off and felt the naked body I hated feel the warmth of the sun. I couldn’t see it, or anything, and suddenly none of this mattered anymore. I couldn’t see all the things I was afraid of, all the things I hated. I could see only shapes and possibilities.

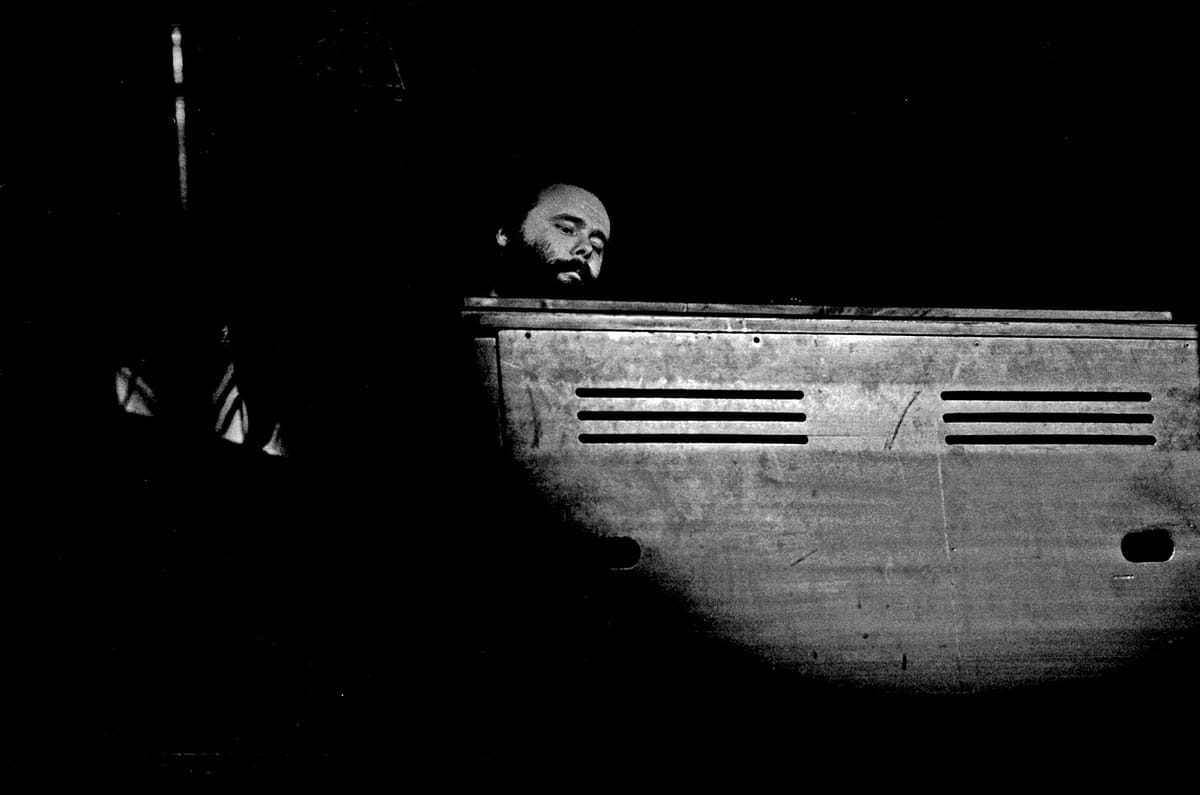

Michael Stipe went on walks with headphones on and the bed tracks of what would become “Man on the Moon” playing in his ears. Looking for something, desperate for it to appear while he was roaming the streets of Seattle, where they were recording. Reflecting on the album for its twenty-fifth anniversary in 2017 with NPR’s Robin Hilton, Stipe said of this song, “Andy Kaufman, somehow, became my Every Man. He became my Hero With a Thousand Faces. And these kinds of larger-than-life questions. Literally larger-than-life questions about existence and about what happens after we’re gone, and did the man really walk on the moon?”

Standing naked out in a campsite by the Yukon River so close to my fears, I grabbed onto the rope and felt its weight and heard voices calling me in from the great beyond I couldn’t see. The shapes and colors and blotches. I held on to the rope and felt my feet leave the ground and swung out past the ground and into the open air and felt freedom for a single second, and then immense and terrible panic as voices from below yelled in fear.

Stipe had been writing songs about death, because he was grappling with death at the time. His grandparents were aging, he had a dog falling deathly ill, he was dealing with the weight of the AIDS crisis. There was something in Kaufman that became the conduit through which Stipe wanted to process all of these things. These themes are present throughout Automatic for the People: death, loss, trauma, growing older, leaving youth behind. How to make sense of a life of sad and dark potholes on the road that led us here.

I couldn’t see the ground or the water and didn’t know when to let go. I could hear yelling but nothing clearly. I thought for sure I was going to die out there naked and half drunk and high on skunk weed in a campsite in the Yukon. It was the Kaufman influence that helped Stipe find the words to “Man on the Moon.” The references to Kaufman’s life and career: Mister Fred Blassie and goofing on Elvis.

Hey baby.

It’s Kaufman’s spirit more than anything that became this conduit. How to find the strength to still ask questions in the face of stark and difficult truths. How to believe that not everything is as it seems to be. How to let go.

I thought I would die out there in the Yukon and decided to just let go and allow death to claim me. I didn’t know if I was over the water or the land, but I just let go. Let go and dropped. My body in the air. I hated my body. Hated this life. Hated my fears. I fell in the air for seconds that felt like decades. I could hear voices yelling. I could hear the end rushing to me. And then my body hit the water with a loud splash and I sunk below the surface.

The story is that Stipe walked into the studio and laid down the vocals for “Man on the Moon” in a single take. They had taken so long to find him until suddenly they were there and ready and all he had to do was release them. Suddenly everything made sense and became clear. It is only in questioning everything, allowing yourself to believe that possibility exists in impossible places and that maybe not everything is as it appears, that it all becomes clear. Learning by failing, by not allowing the truth to interfere with our desire to make sense of the one life we are given. We can decide how our story will be told and how we might be remembered.

I was pulled up to the surface by hands and anxious shouts. I couldn’t see, and I splashed about wildly as my body broke the tension of the surface. Panic. I must have looked like a feral animal dunked in a bathtub. Friends tried to calm me but couldn’t. I hadn’t told anyone of my fears. And now I couldn’t even see to make sense of the world around me. I was floating in the water surrounded by shapes and colors and nothing and I wasn’t dead. I was panicking; I was alive enough to panic. Hands held onto me with concern and fear until I finally found my center and could relax for a second. And then I laughed, laughed hard from somewhere in my body that had been holding on to so much fear for so long.

“Drive” is the thesis of Automatic for the People, laying out this theme of anxious growth into adulthood. It’s haunting and dark and somber. It’s the act of looking up the road and seeing death reflected in the taillights ahead. “Man on the Moon” is the answer to this fear, that death is only part of this story, not the end or the ultimate fear. That there is room here to question and wonder and allow ourselves to let go. To commit to the difficult bits and choose how we live this life. We don’t know the truth of Kaufman’s life, but we know how Michael Stipe imagines it as he sings to the end of it all. We don’t know the secrets of death, and all we can do is find the right conduit to process our difficult feelings about the fear surrounding it. “Man on the Moon” sees the fear riding in “Drive” and begs you, you who are out swinging on a rope above what might be water or might be land, to just let go. Don’t worry about the truth of all these difficult memories; you can still choose how you want to remember the hardest parts.

Used with permission from the University of Texas Press, © 2025.

Lovely stuff right?

Paid subscribers stick around for another new poem and the interview with Noel Gallagher.