25 comics you should read

Something in here is for you personally

Every now and again I think I should really get back into reading comics. Reading anything besides posts come to think of it. Not too long ago I went back and re-read all the shit like Hellblazer, Swamp Thing, Sandman, Animal Man, Doom Patrol etc. and then I came up against a familiar problem: there's too much other stuff to choose from. I was paralyzed by an abundance of choice as it were. Kind of the opposite of trying to find something to stream on TV lately. As luck would have it I remembered that my buddy (and Flaming Hydra partner) Sam Thielman is something of an expert on all things comics so I asked him to put together a list of must-reads for me and for you. Hopefully we'll all find something we love in here.

This was previously for paid subscriber only but I've opened it up for a bit. Please consider helping to pay for our great contributors.

On Saturday we went back to Harvard Square for the first time in a while to have dinner with friends and go see The Sheila Divine at The Sinclair – still after all these years my favorite Boston band and favorite venue. For a good while the four of us walked around the Square remembering out loud to one another what different businesses used to be. That bank branch was a beloved dive bar. That shitty restaurant was a good restaurant. The long since abandoned movie theater was a movie theater.

I ducked into the Harvard COOP real quick to see if they had A Creature Wanting Form for sale and was happily surprised.

I also went into Charlie's for a drink and as I was walking upstairs I heard the sound of children squealing and thought hm that's odd. When I turned the corner by the jukebox I realized the entire room was filled with children. Like they were having a really big 10th birthday party in the shitty old punk space. I was emotionally prepared to be surrounded by people younger than me but this seemed a little on the nose.

I thought of this old piece from the first year of Covid:

It’s September and the list of beloved longstanding bars and restaurants closing down for good in Boston and Cambridge keeps growing.

But by the time I’d arrived twenty years ago I thought it was already over. That was the sense I had anyway. That the Boston I now inhabited was some imperfect and diminished version of what had come before. Shuttered clubs and bars and diners where matters of significant local folklore had transpired and defined life for the previous generation were lost to time they said.

This likely happened in whatever city you came of age in as well it’s the same story anywhere. Everything was always some degree better before in a time you no longer have access to. This is a lie in many ways and a story people tell themselves to mythologize their own youth but it can also be true. Things can and do very often get worse.

They can also get better though and so you nonetheless find your own places and make of them what you can and conspire in the erection of new monuments to joy and then twenty years on as the marriage of progress and entropy has its sour way with your life this time you pass on this sense of disappointment to your younger friends who listen but only so much. You know things but you don’t know everything. You know what happened but you don’t necessarily know what is happening.

A neighborhood’s soul is lost then rebuilt then lost again and it goes on and on but there is I think a potential end point where the predictions of a neighborhood’s demise can finally be fulfilled and maybe that’s here for Boston and for similar cities. Places with an abundance of soul can drag out the process for a long time but there are only so many blows they can take. My beloved Harvard Square has continued to be a cultural destination for all these years of loss simply because there was so much to lose in the first place. Now every other storefront is a bank branch.

And this new one that will probably go in the next book:

Boston, Massachusetts

We were back in the city for the first time in a good while and not recognizing many of the new businesses or even the skyline itself a melancholy overrode the initial excitement of it. The criteria for my melancholy is not especially rigorous to state the obvious but I mentioned it to some friends later and we talked a bit about nostalgia for our youth and the pain of that but it wasn’t quite getting it right. I'm not pining for something that is unattainable like the past I'm frustrated by not having access to something that still exists which is the city. It's all still right there just without me inside of it.

I thought of the old Bobcat Goldthwait joke:

"I lost my job. Well I didn't lose it. I know where it is. There's just some other guy doing it now."

The next day we walked around our perfectly nice suburban town and it was perfectly nice. I stopped to take a picture of a fire hydrant that’s in the process of being swallowed up by the overgrowth of brush on a quiet street by the river and thought of the end of the world. The criteria for me thinking about the end of the world is also not especially rigorous.

It's not the same of course. Out here. Nowhere. It does not nourish me in the way the city does. Did.

I need to be around people. Strangers.

I long for the camaraderie of our shared indifference to one another.

I wish for no one to care that I even exist.

The community in that.

25 comics you should read

by Sam Thielman

Luke asked me to do this and I’m not sure he knew what he was getting into. I have a list of over 100 of my favorite comics, just sort of hanging out on my phone. I add to it and prune it back regularly, because like every nerd I love making lists. I had a few rules for this version, since it’s for public consumption: No books no normal person will ever buy because they’re out of print, (so tearful farewells to MAD and Cages and Corto Maltese, among too many others.) No artist or writer more than once. Nothing that only exists digitally. Nothing currently ongoing. And nothing that requires prior knowledge of the artist or a particular genre, which is why there’s not much superhero stuff here. Beyond that, the sky is the limit, so here’s what I came up with. I have horribly neglected my responsibility to pick only a select few books, but that means there’s more for you to choose from. Everything is good. Something in here is for you, personally.

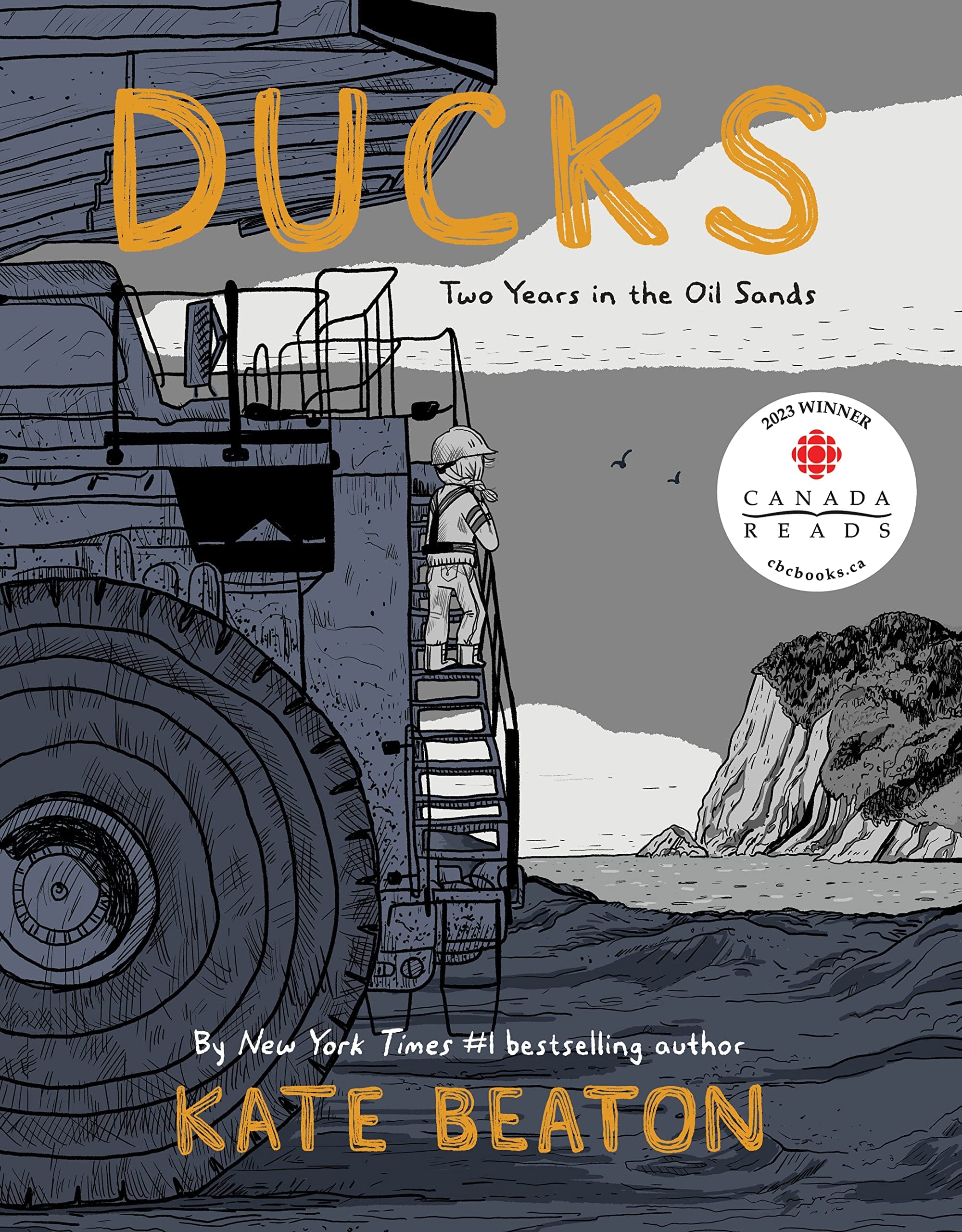

Ducks by Kate Beaton

If you like Luke’s newsletter and want to read something smart and funny and drawn from the deepest insides of a person who has had to compromise every part of herself to get by in a world that requires you to be of use to capital, you should probably read Ducks today. Tomorrow at the latest. That’s assuming you haven’t already read it. Kate Beaton is part of the original mid-aughts webcomic renaissance with Chris Onstad who did Achewood and David Malki (Wondermark) and Randall Munroe (xkcd). Beaton’s sister died and she said she couldn’t do funny comics about Jane Austen anymore, so she stopped drawing her wonderful gag strip Hark! A Vagrant, and then, after several years went by, she suddenly had this gigantic graphic novel about being a kid from the sticks in Nova Scotia whose only hope for the future she wants is to go take an incredibly dangerous job in the oil sands. It’s all true.

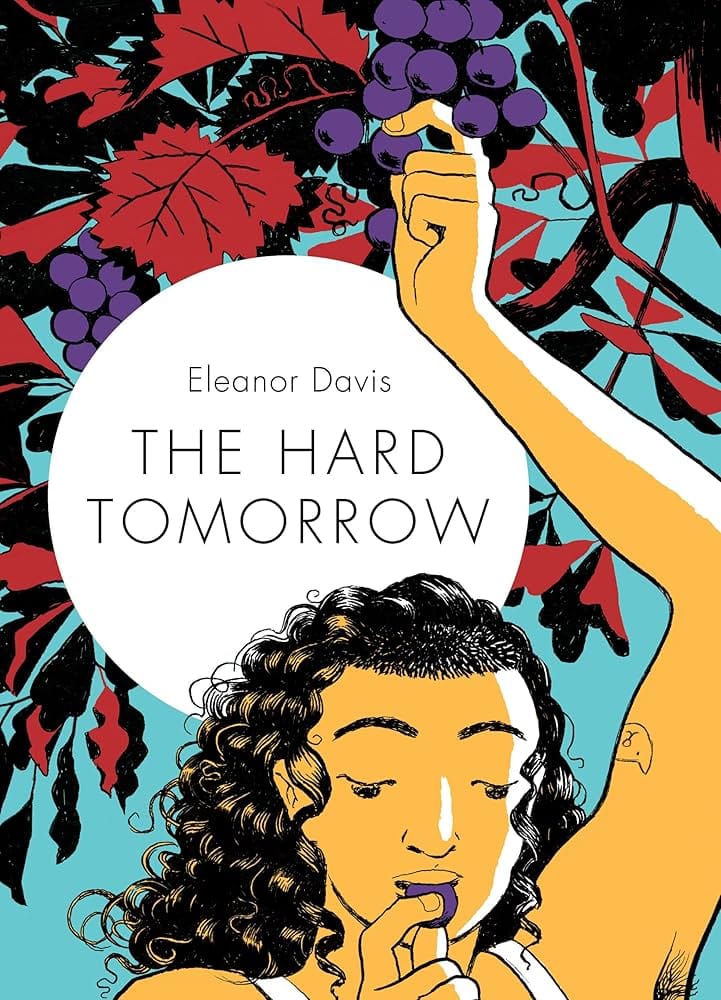

The Hard Tomorrow by Eleanor Davis

Just an extremely good book about The Way We Live Now. It gets right to the heart of why it feels futile to try to eke out a living when our entire society seems to want you to die, and what makes it worth doing anyway. Also the cartooning is awesome.

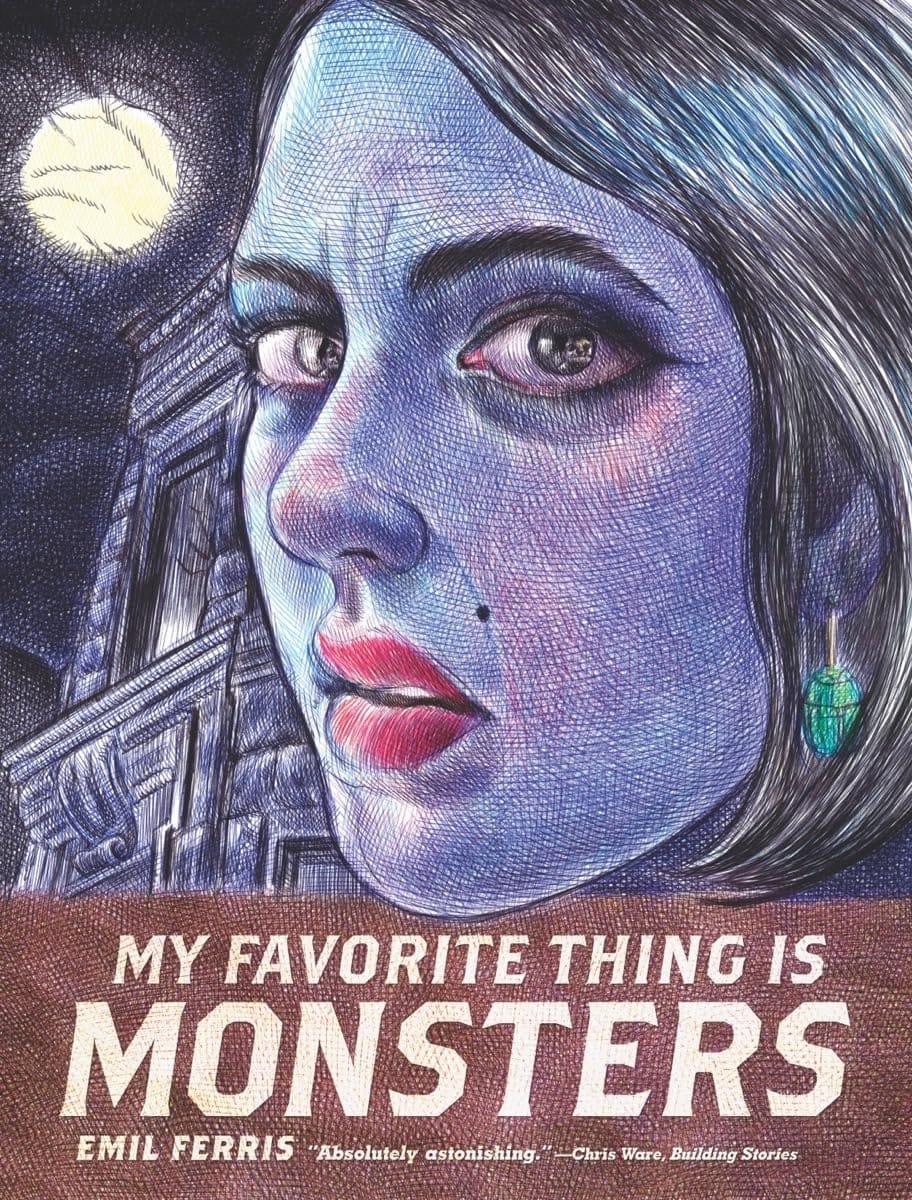

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters by Emil Ferris

Emil is a genius. I remember when I asked her publisher what was new and good from them and he tossed a gigantic proof of this book at me. At first I thought it was a new Robert Crumb book—it’s that technically accomplished. The renderings of classical paintings in multicolored ballpoint are just brain-destroying. It’s a murder mystery set in 1960’s Chicago, and both volumes are huge shaggy dog stories that can consume you for days when you’re reading them.

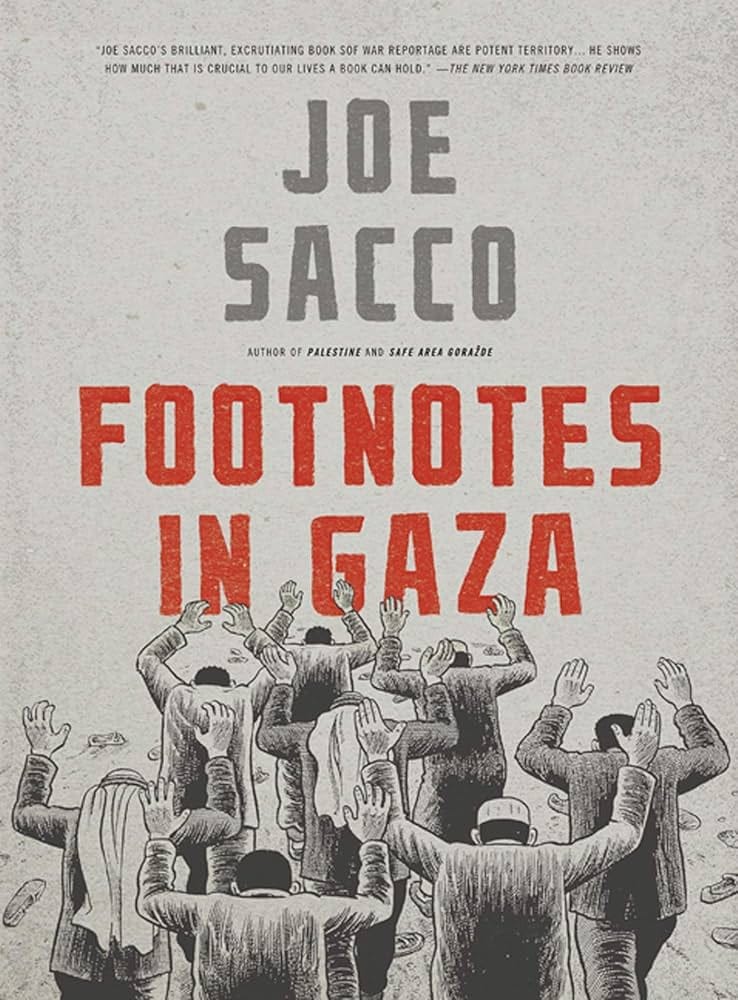

Footnotes in Gaza by Joe Sacco

Between this book, Palestine, and his new one, War on Gaza, Joe Sacco has probably produced the most accomplished body of general-interest journalism about Palestine in English. This is his masterpiece, a delicate book about the unreliability of memory and the necessity of record-keeping in the face of an especially cruel form of oppressive lying, where the IDF and the broader Israeli government conspire to pretend that they haven’t destroyed your home and family.

Sunday by Olivier Schrauwen

Rusty Brown by Chris Ware

Glenn Ganges in The River at Night by Kevin Huizenga

I’m grouping these three together because they’re the three best books I know that try to directly mimic how your imagination works. One reason I love comics is that I think their connection of static images linked by inference maps onto the nature of memory better than any other form. We impose linearity on collections of impressions and thoughts; a blue jacket, blond hair that needs cutting, glasses, shoes—these are the details we assemble into a person when we can’t see that person in front of us. Schrauwen, Ware, and Huizenga all try to tell us a story about this quality in different ways, and each book is virtuosic. Describing the plots of any of them is pointless so I’m not going to, but if you enjoy the kind of American literary maximalism that draws on Joyce and the Russian novelists, these are for you.

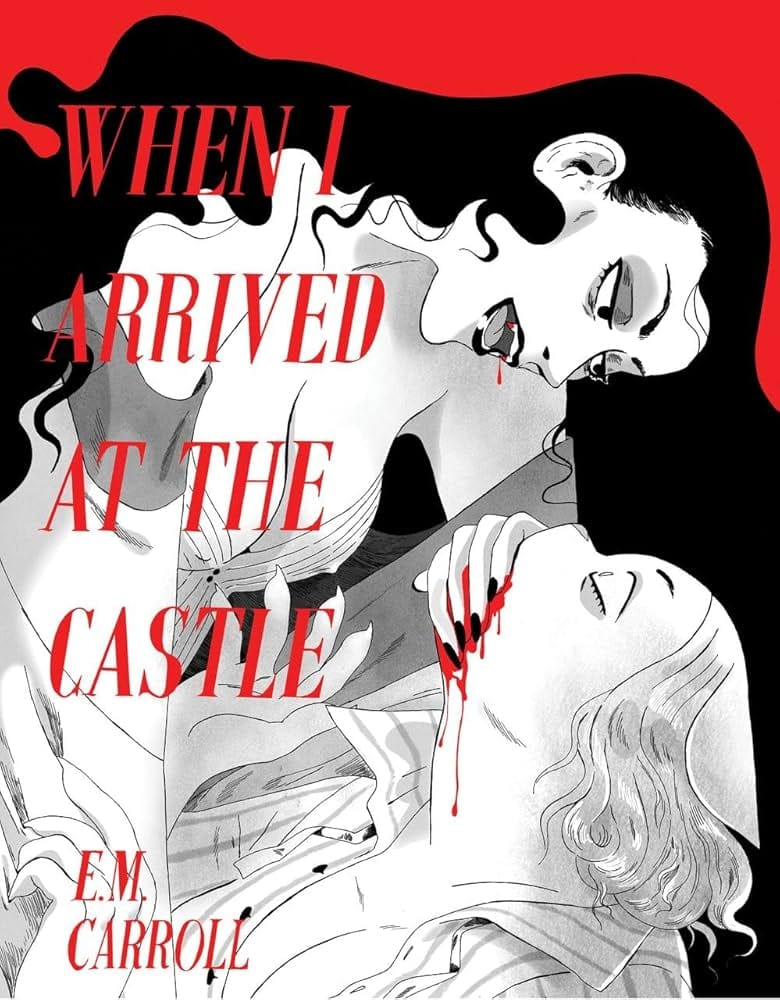

When I Arrived at the Castle by E. M. Carroll

Carroll is probably better known for their book of short stories Through the Woods, but this little novella is my favorite of their work so far. It’s a horror story fairy tale that seems like it’s going to work out in a sort of feminist-revisionist Angela Carter mode and then it goes absolutely crazy.

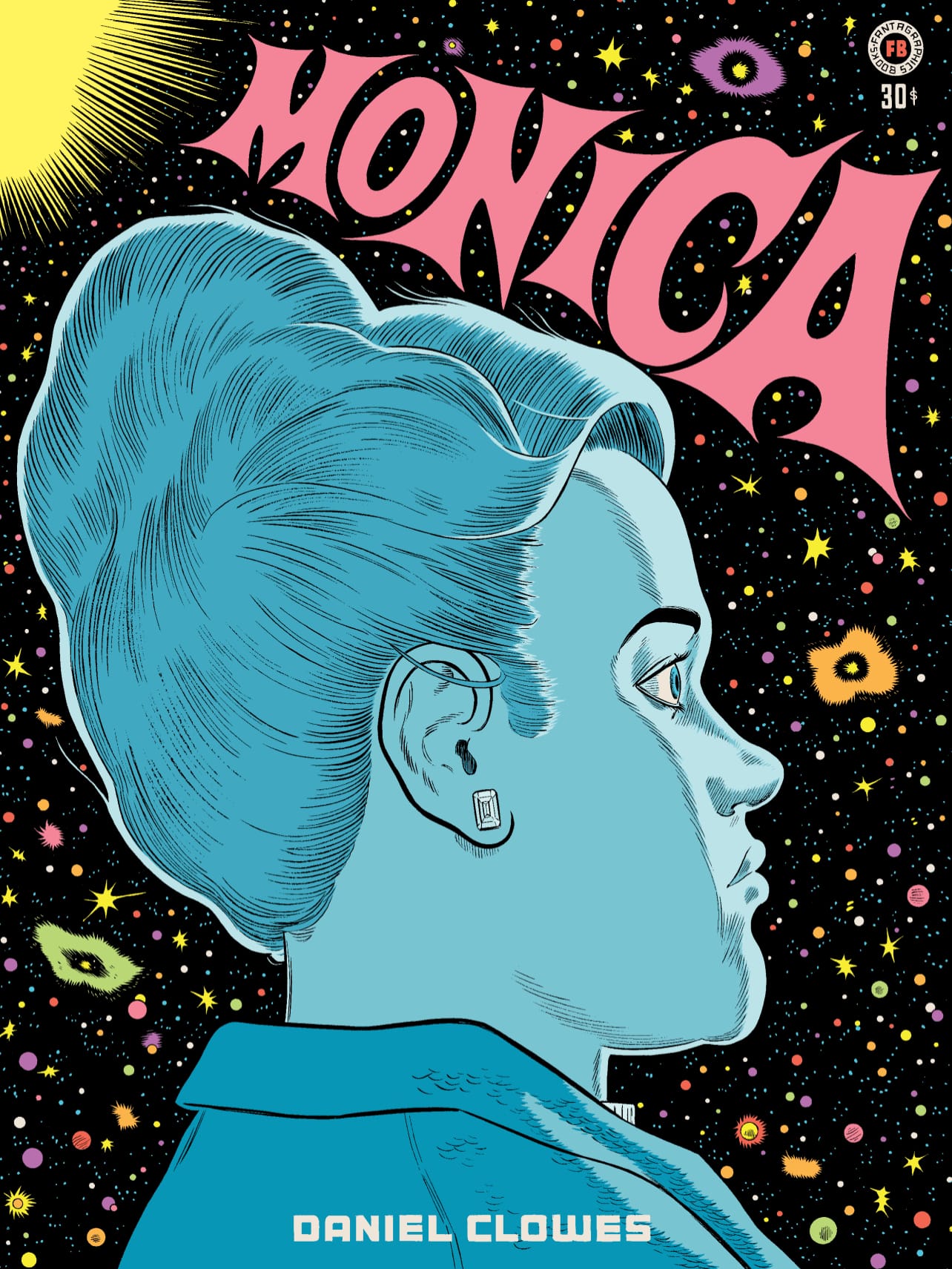

Monica by Daniel Clowes

This is a work of social-realist fiction about the woman who brings about the supernatural apocalypse. Some days it’s my favorite comic. Clowes is the alt-comix answer to Steve Ditko, the guy who created Spider-Man and Doctor Strange.

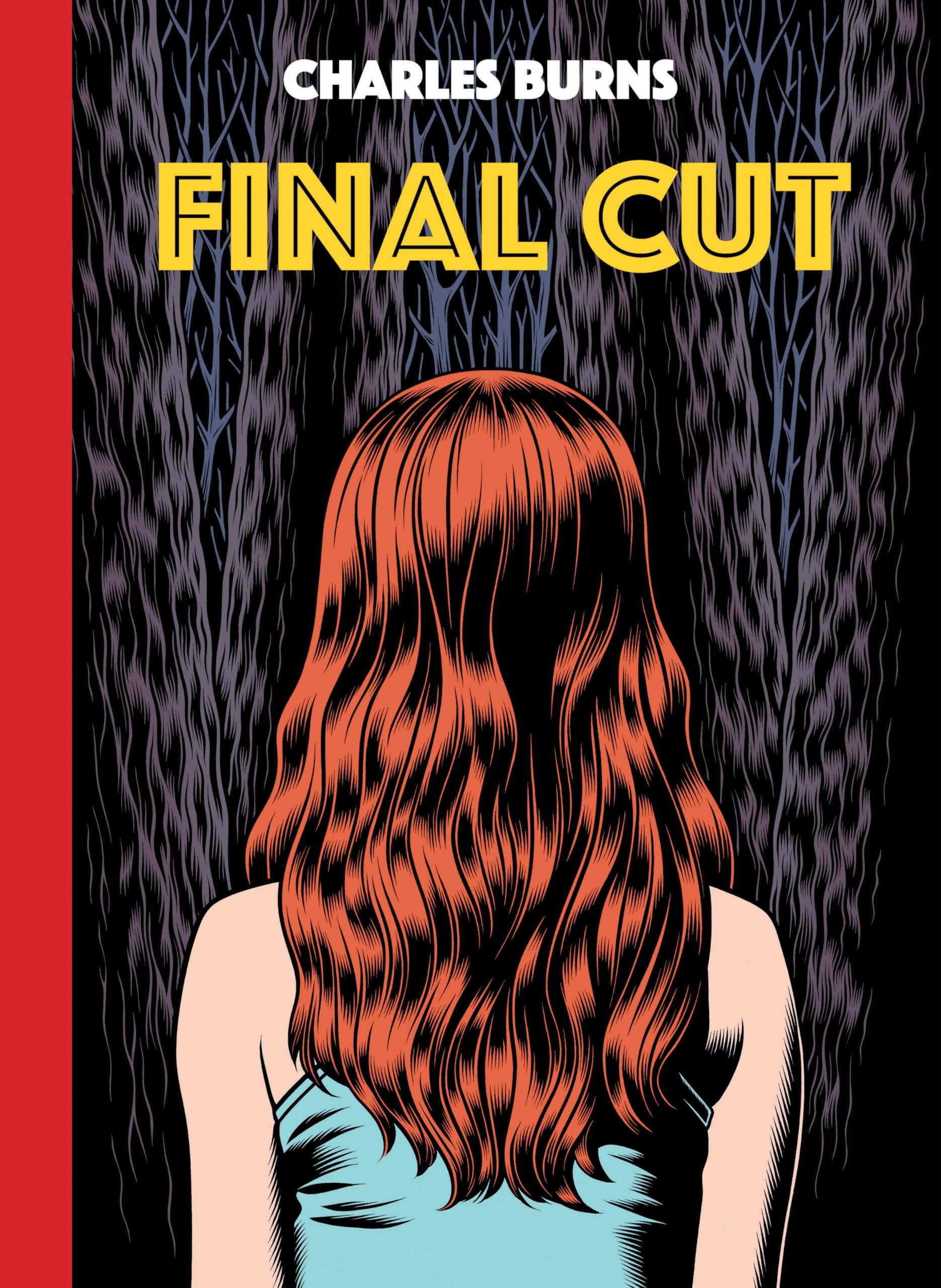

Final Cut by Charles Burns

There’s a long history of romance comics in pop art—you’ve seen the Roy Lichtenstein paintings riffing on them. This is a romance comic as pop art. If Clowes is Ditko, Burns is Jack Kirby.

Bone by Jeff Smith

This is both a loving homage to the old Duck Tales-inspiring Carl Barks Disney comics and a high fantasy story that aspires to be the Great American Novel. It’s hugely popular, and a great way to get kids into reading, but it’s also just terrific storytelling.

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen by Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill

There are like ten Alan Moore books you should probably read. Miracleman inspired every superhero comic for at least twenty years; his and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen is a classic sci-fi story that mostly came true; Moore and David Lloyd’s V for Vendetta is the utterly pure manifesto of a furious young anarchist. Top Ten and Swamp Thing and Tom Strong do pretty much everything superhero comics could ever be expected to do. But The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is the best one. Kevin O’Neill is Moore’s ideal collaborator— an impossibly literate artist absolutely obsessed with dirty little details. And the story, which borrows characters from Dracula and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, among literally hundreds of others, is about recovering from the horrors that made you hard enough to survive, and is genuinely beautiful.

Locas by Jaime Hernandez

The greatest comics series ever written; imagine Proust as a telenovela. Read it and ruin yourself for everything else.

Tintin by Hergé

Tintin is the original reporter-adventurer, before Clark Kent or Peter Parker. French-language comics work in very different modes from English-language comics; if you want to understand one of its main traditions—and you do, because it’s gorgeous and rich—you can get it pretty much immediately by reading a Tintin book. My favorite is The Calculus Affair. A lot of them are incredibly racist, which is true of other important comics like Will Eisner’s The Spirit, too. Another reason comics are interesting to me is because they’re a kind of unedited record of the past in a way that film and literary fiction simply aren’t—Georges Remi (GR/RG/Hergé) serialized the early Tintin stories in a right-wing Catholic newspaper in Belgium. Tintin’s first editor was tried at Nuremberg for collaborating with the Nazis. Remi went to work for a paper controlled by the Nazis during the war and was regularly accused of collaborating after the Nazis left power. His work is hugely influential on every kind of comics, and while it’s worth reading, it’s especially worth reading with that in mind. There’s a big-budget cartoon version made by the guy who directed Schindler’s List; I’m never sure what to do with that.

Maus by Art Spiegelman

Maus is more or less omnipresent and has been since its publication; it’s still at the center of book-ban debates and a regular feature in school curricula. Perversely, this makes it easy to forget what a good, compelling read it actually is. It’s not exactly a Holocaust memoir—it’s a memoir of generational trauma, drawn by a guy who can’t escape his dad, a pushy and self-absorbed old misanthrope who survived Auschwitz either because of the qualities that get on his son’s last nerve, or acquiring those qualities in the process.

We3 by Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely

Quitely is an unequaled spatial thinker; Morrison is a passionate animal rights guy with a great sci-fi imagination. This is their insane ultraviolent animal adventure book.

One Beautiful Spring Day by Jim Woodring

There’s a weird little dude named Frank who looks like he stepped out of a Betty Boop cartoon, who gets bullied and seduced and occasionally murdered by unknowable monsters in Jim Woodring’s wordless, peerless Frank books. This is the longest and wildest one; every page is like a woodcut rendering of a hallucination.

The System by Peter Kuper

Another wordless book, this one by Kuper, who founded the earnest antiwar magazine World War 3 Illustrated. It’s about the ballooning consequences of small actions within capitalism, a thing you’d think would need words.

Bttm Fdrs by Ezra Claytan Daniels and Ben Passmore

Speaking of capitalism, Ezra Claytan Daniels and Ben Passmore’s Bttm Fdrs is the only horror story I know of that deals directly with cruel landlords and the class divisions in housing. It’s paced like a good movie, its visuals are sparklingly clean, and god is it funny even when—especially when—it’s horrifying. In a just world it would have a readership of the same size as Saga or Batman.

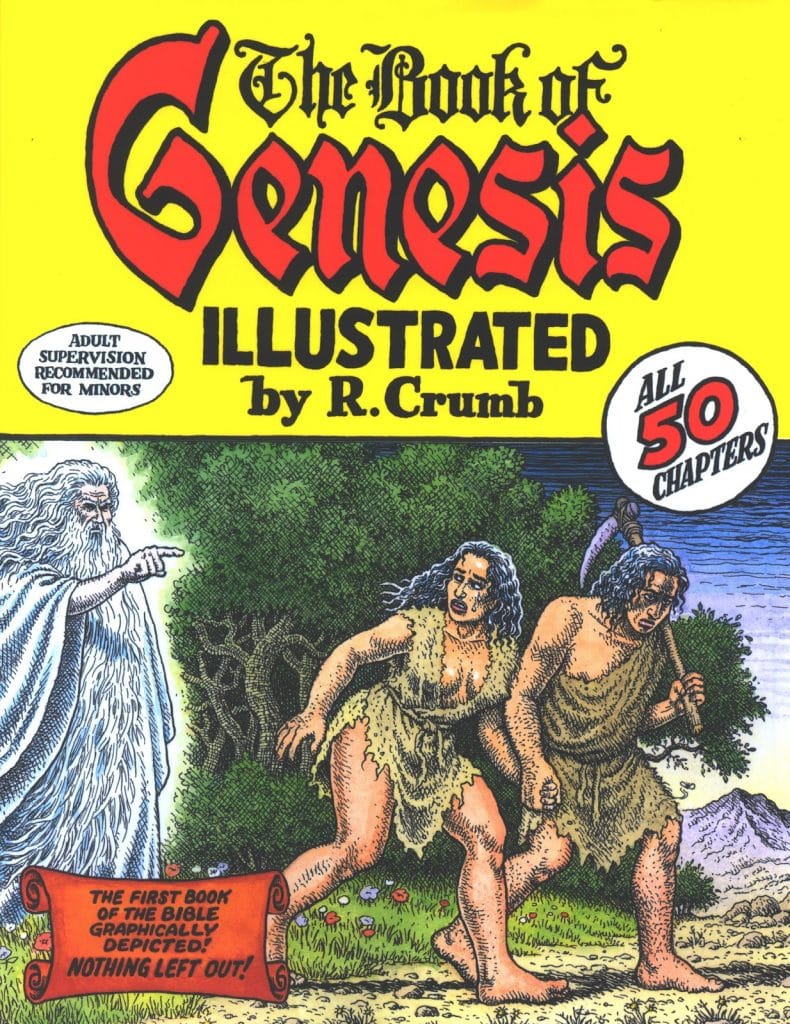

The Book of Genesis Illustrated by R. Crumb

I have a big collection of Bible comics; everybody from Alan Moore to Basil Wolverton (you know, this guy) has taken a whack at the Good Book at some point. Crumb’s is my favorite; it uses Robert Alter’s very literal 1996 translation of Genesis and renders every incident without irony, but also without pretense. Lot’s daughters definitely get him drunk and rape him. You realize about halfway through that a lot of Christian scripture is about women tricking men into having sex, and that these are the stories from which the rules and strictures of the Catholicism that contributed to Crumb’s psyche emerge. It’s one of the clearest interpretations of the Bible I know.

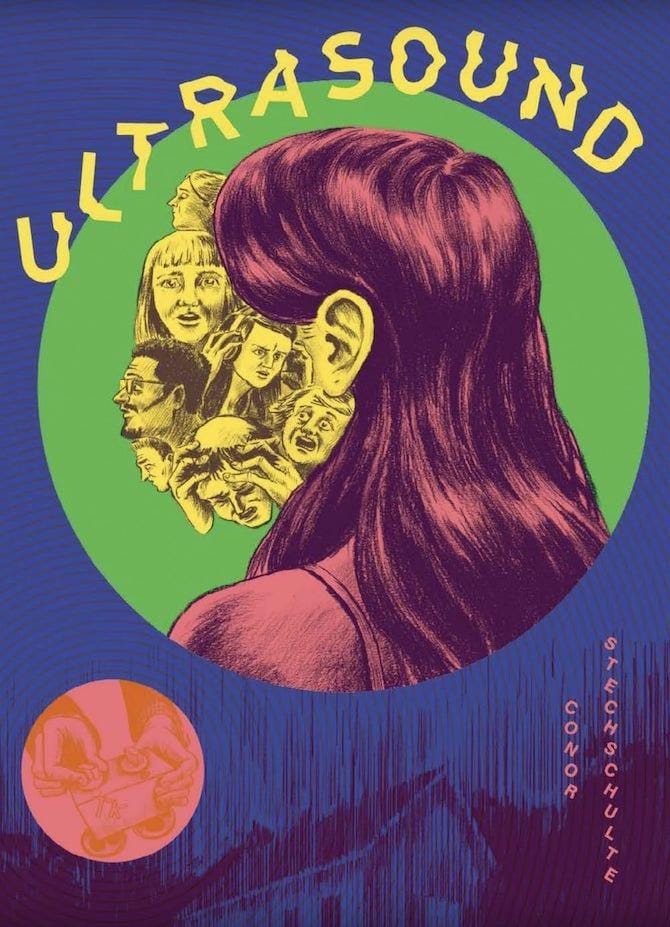

Ultrasound by Conor Stechschulte

I slept on this book for years,and can’t remember why I finally picked it up, but it’s incredible. It’s a very tense, weird story of mind control and espionage and it’s drawn in such a way as to add additional visual layers every time the story gets more complex. An underappreciated masterpiece.

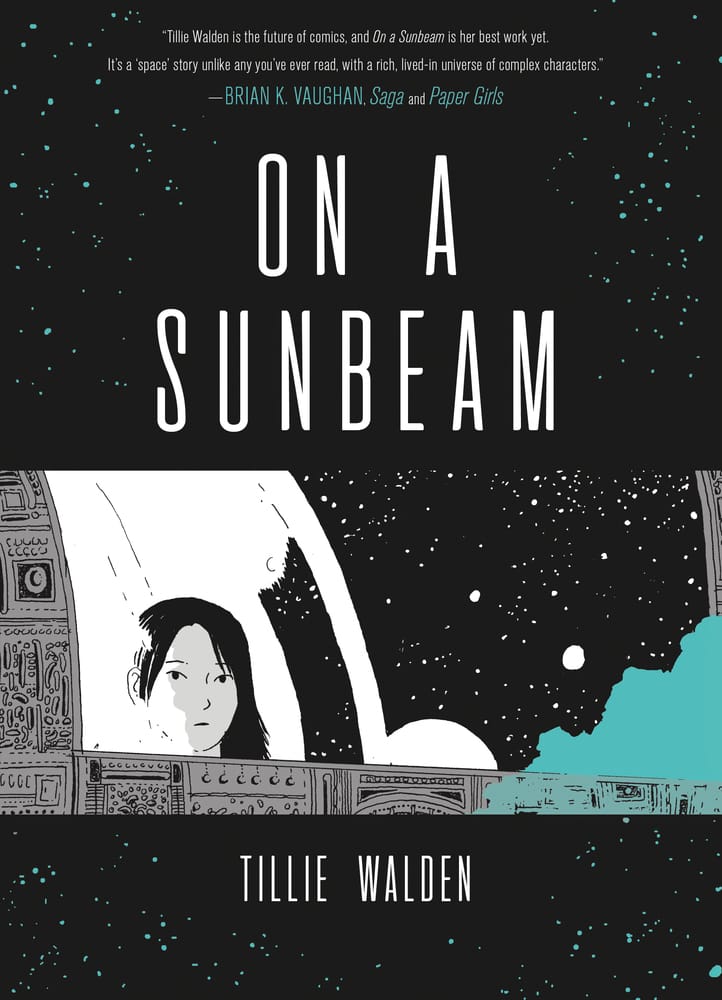

On a Sunbeam by Tillie Walden

Walden’s earnest, sweet sci-fi webcomic eventually turned into one of the thickest books on my shelf. It’s a subtle story about young people in love in a future where time itself is completely broken.

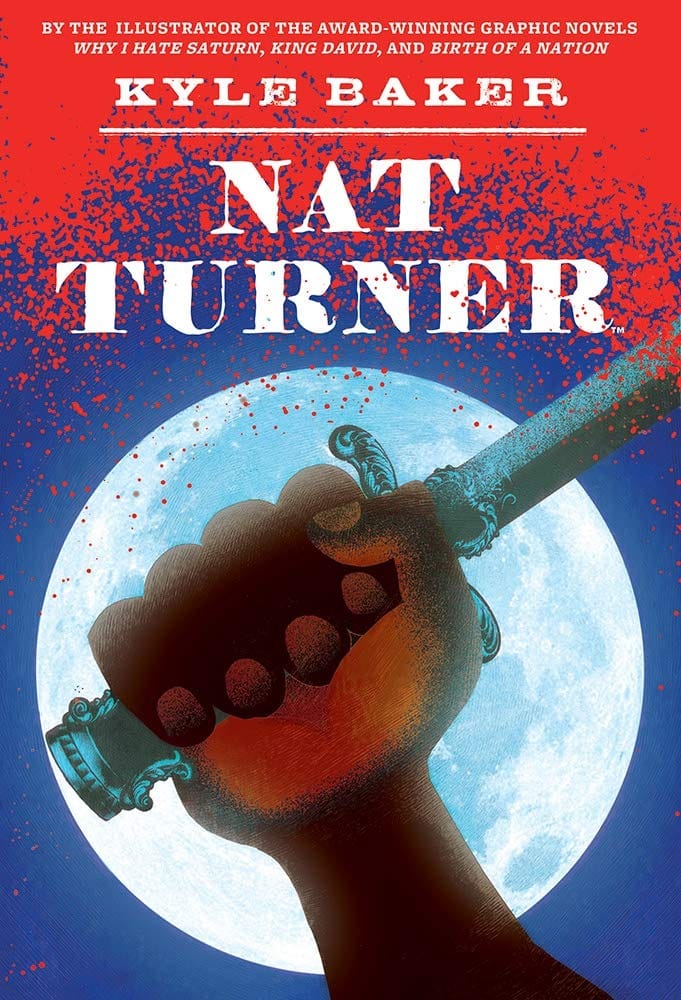

Nat Turner by Kyle Baker

This is another book, like Crumb’s Genesis, that takes a story most people think they know and reminds you of the details, which are almost diametrically opposed to the cultural sense of the thing. We think of Turner’s slave revolt as glorious because slavery was so evil; in fact the evils of slavery made the entire thing worse and bloodier. Baker has a history in animation as well as comics and he combines realistic figures with drawings that would look at home in a Looney Tunes short; the result is jarring in a very effective way.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind by Hayao Miyazaki

Miyazaki’s rightly beloved movie adaptation of his own comics covers about a third of the material in the books, which expand his dying future world into something as rich as the fantasies of Tolkien or Gene Wolfe. Nausicaä herself has all the righteousness of youth and Miyazaki refuses to undercut her or condescend to her; instead, he makes her strong enough to take on the challenge of living in harmony with a world that seems to be rejecting her whole species. It’s only gotten more timely.

Akira by Katsuhiro Otomo

If you’ll indulge me one last pick from the '80s, Akira, like Nausicaä, is so much bigger than the better-known film that the latter feels like a few sample chapters of a far richer narrative by comparison. It’s a story not just of the kind of Cold War fears that dominated American culture from the fifties until the end of the Reagan era, but of the actual aftermath of nuclear destruction, something that colored Otomo’s childhood in the way it could never have affected an American artist. It also ascends to incredible heights of scale and ambition. The tortured antagonist punches a hole in the moon!

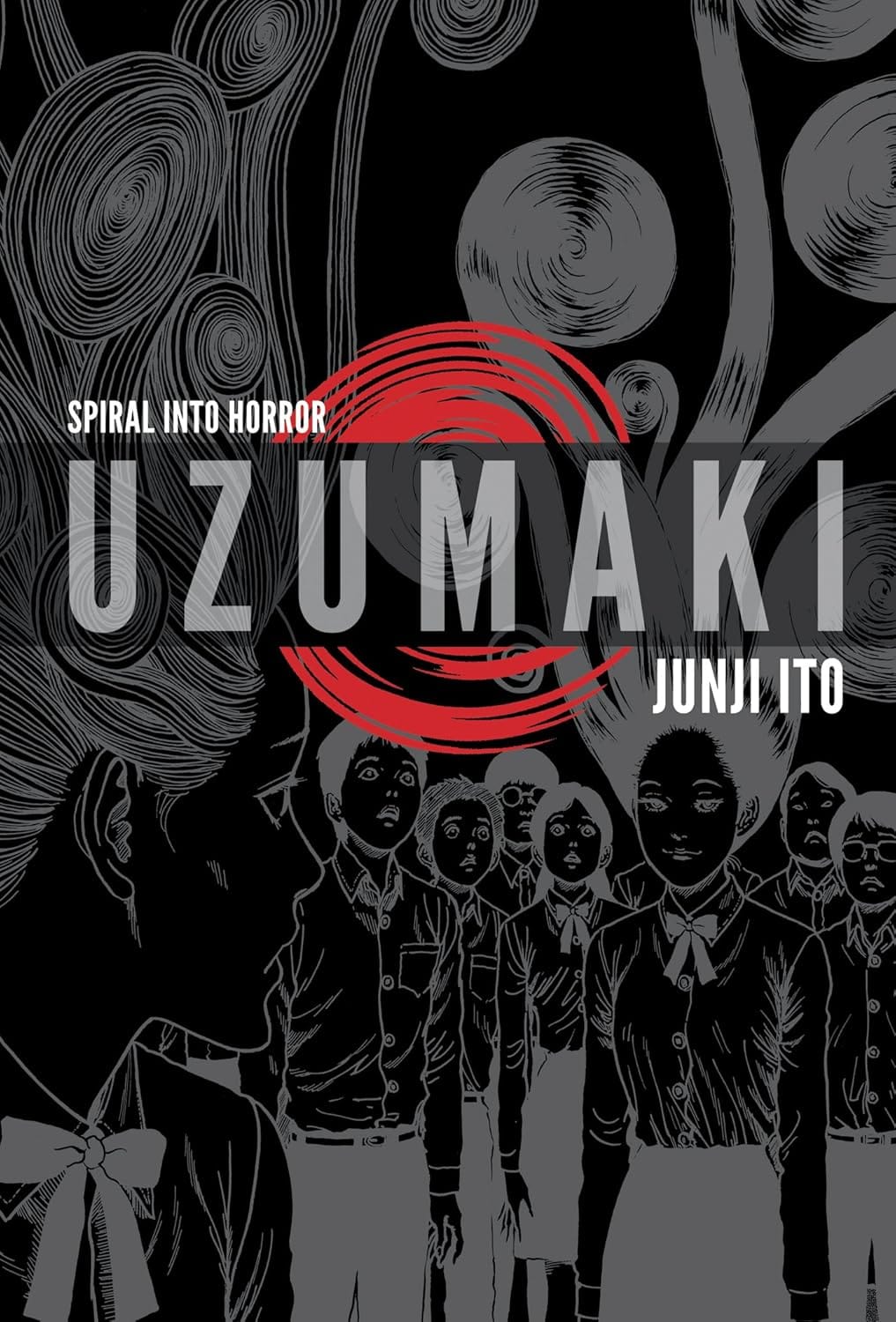

Uzumaki by Junji Ito

Ito’s big breakthrough is as good as everyone says it is. The title means “spiral” and the story structure is a gyre that widens until it swallows… well, everything.

Sam Thielman writes about comics for The New York Times Book Review and sometimes The New Yorker, and contributes essays and fiction to Flaming Hydra. He also edits Spencer Ackerman’s national security blog FOREVER WARS. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son and cat.