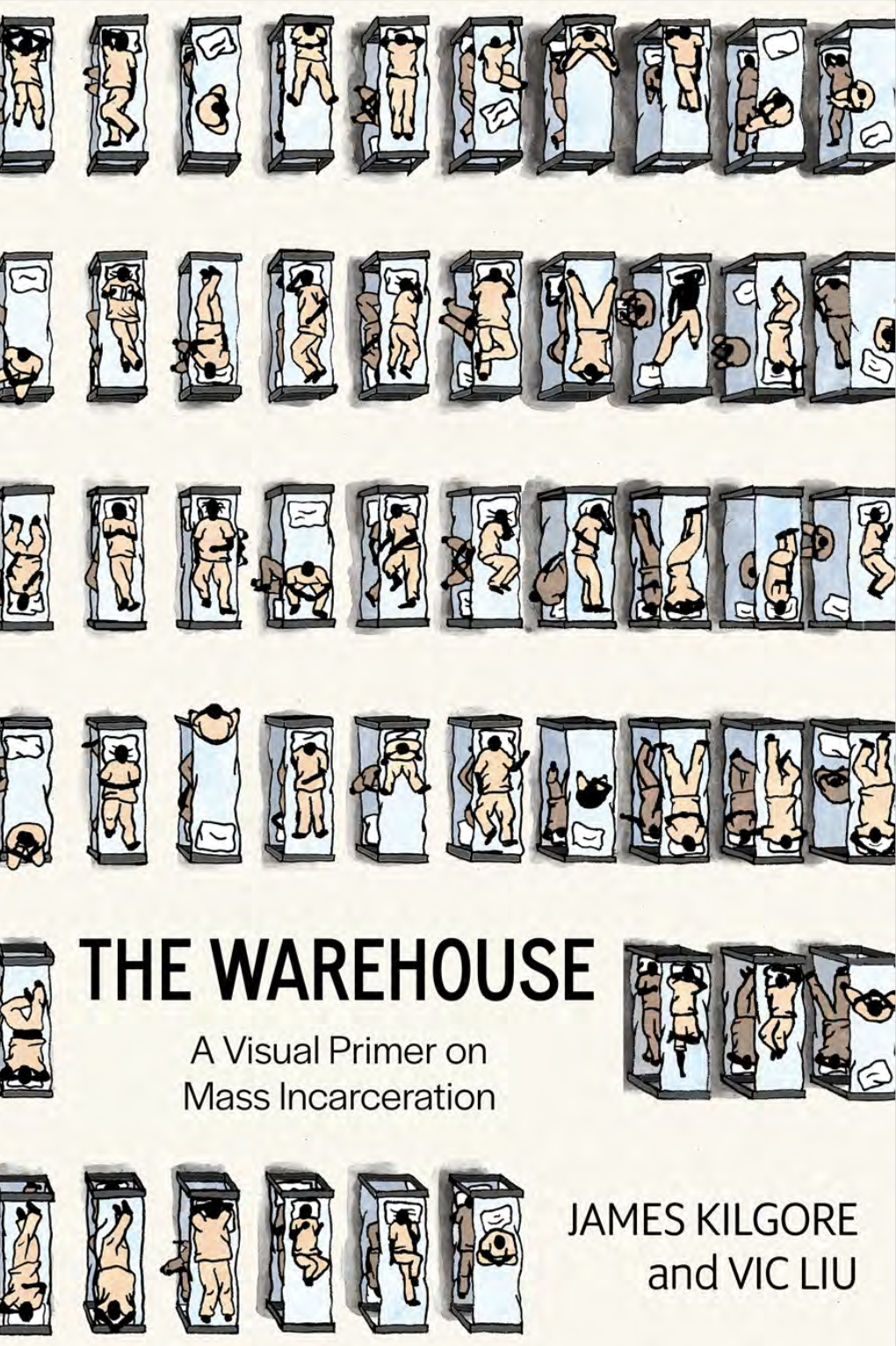

The Warehouse

The largest system of incarceration in human history

Today an excerpt from the new book The Warehouse: A Visual Primer on Mass Incarceration (PM Press) by anti-carceral author and activist James Kilgore and illustrator Vic Liu.

The book is a clear and concise overview and granular look at the sheer brutal scope of "the largest system of incarceration in human history," and the economic and political machinations that have gotten us to this low punishing point.

As it notes by way of introduction:

The US incarcerates more people than any other country, incarcerating roughly 20% of the entire global prison population. By contrast, the US population is only 4% of the global population. The US incarcerates 5 times more people than proportionate to its population.

As of 2022, this system held 1.9 million people in a total of 1,833 state prisons, 110 federal prisons, 1,772 juvenile detention facilities, 3,134 local jails, 218 immigration detention facilities, and 80 Indian Country jails. By comparison, in 1980 the combined prison and jail population was just over 500,000.

It also presents testimonials from people who have lived or are living inside of that oppressive structure, and a vision for a better possible future from activists and abolitionists working toward us getting there.

The excerpt below concerns the conditions for marginalized people in prison, including women, elders, LGBTQ+ individuals, and people with disabilities.

It also has a section on the nightmares of solitary confinement, with selections from the Photo Requests From Solitary project that I wrote a poem about in A Creature Wanting Form which went like this:

For recent writing in Hell World on incarceration see this piece on "pay to stay" rules, where inmates are charged $50-100s a day for room and board. Sometimes, like in Florida, they're charged for their full original sentence, not just the time they actually serve.

Or this piece on prison gerrymandering, which incentivizes state legislative districts to house as many prisoners as they can, usually transferring them from urban to rural areas, in order to inflate their local population, and thereby their political power.

I had another story go up at Flaming Hydra this week. I think it's my favorite I've done over there (or anywhere) in a while. As a change of pace I decided to write a melancholy piece about the passage of time and mortality and familial disfunction using the Maine coast as a metaphor.

It starts like this:

The first thought is dad sprinting back and forth across 95 somewhere north of Boston. Like an old tabletop video game. Salvaging as many items of our wind-strewn clothing as he could. One of those tubes they make you stand in and the air blows the cash around. He must not have secured the suitcases well enough to the roof of the station wagon. Mitt Romney with a dog. Ours was safely inside though. An Irish setter named Arlo crouching in the backseat panting and staring dumbly at things he didn’t understand and didn’t need to anyway.

It doesn’t seem worth it to me now. Risking all of that. But I’ve never had to pay to clothe children. Especially ones that aren’t technically my own.

My mother’s family had been coming summers to stay at a defunct cove-side motel in this no stoplight town since they were children. Then at a small house of their very own. Next door to one church and across the street from another. Imagine New England on a postcard. The one hundred year old general store. Lobster traps everywhere even on land. Fried clams and ice cream and cold sadness like the water a few inches beneath the parts the sun reaches.

OK now imagine it all slightly poorer than what you were thinking. Just a town. A town in Maine. Sunburnt men in overalls who knew how to do things and then died early for having done them.

Ok here's the excerpt.

Please chip in to help keep this newsletter going. Thanks as always for reading.

Marginalized in Prison

The overwhelming majority of the prison population is poor, with Black, Indigenous, and Latinx folks disproportionately targeted. Other marginalized groups are also overrepresented in the prison population and face their own particular challenges behind bars. Women often are denied adequate access to reproductive health, as exemplified by the struggle to access tampons or menstrual pads. Trans people are not only denied gender-affirming care and support but also face abuse and discrimination such as solitary confinement.

Though the Americans with Disabilities Act is supposed to guarantee equal treatment and accommodations, people with disabilities in prison face isolation, harassment, and especially poor medical treatment. Furthermore, as the population of people with long sentences meted out by mandatory minimums ages, more and more people are growing old in prisons without the equipment, support, or care they need.

Elders in Prison

Getting Old behind Bars

On average, more than 10% of people in state prison are 55 and older. This population grew by more than 400% from 1993 to 2013. By 2016, for the first time, those over 55 made up a larger share of the state prison population than those between 18 and 24. The growing number of elderly people in prison is largely a product of harsh sentencing legislation like mandatory minimums, enhancements, and truth in sentencing. The frequent imposition of life sentences played an important role as well. By 2019, more than 200,000 people were serving life sentences in state and federal prisons.

Keeping elders in prison creates many problems. For instance, elders have more health issues than younger people. This increases the costs to the state of keeping such individuals behind bars and impacts their lives if they are eventually released. The absence of effective health care in prison ultimately means that incarcerated people tend to age faster than the rest of the population. One study in Pennsylvania showed that the health of a group of men in prison who averaged 57 years of age had a health profile comparable to men in the community who were 72.

“A friend of mine once pushed me in my wheelchair while returning from our meal. He is 91 years old and calls me a kid; I recently turned 56. When I asked him when he would be released, he ignored my question. I don’t plan on asking again.”

-ERIC FINLEY, incarcerated in Florida

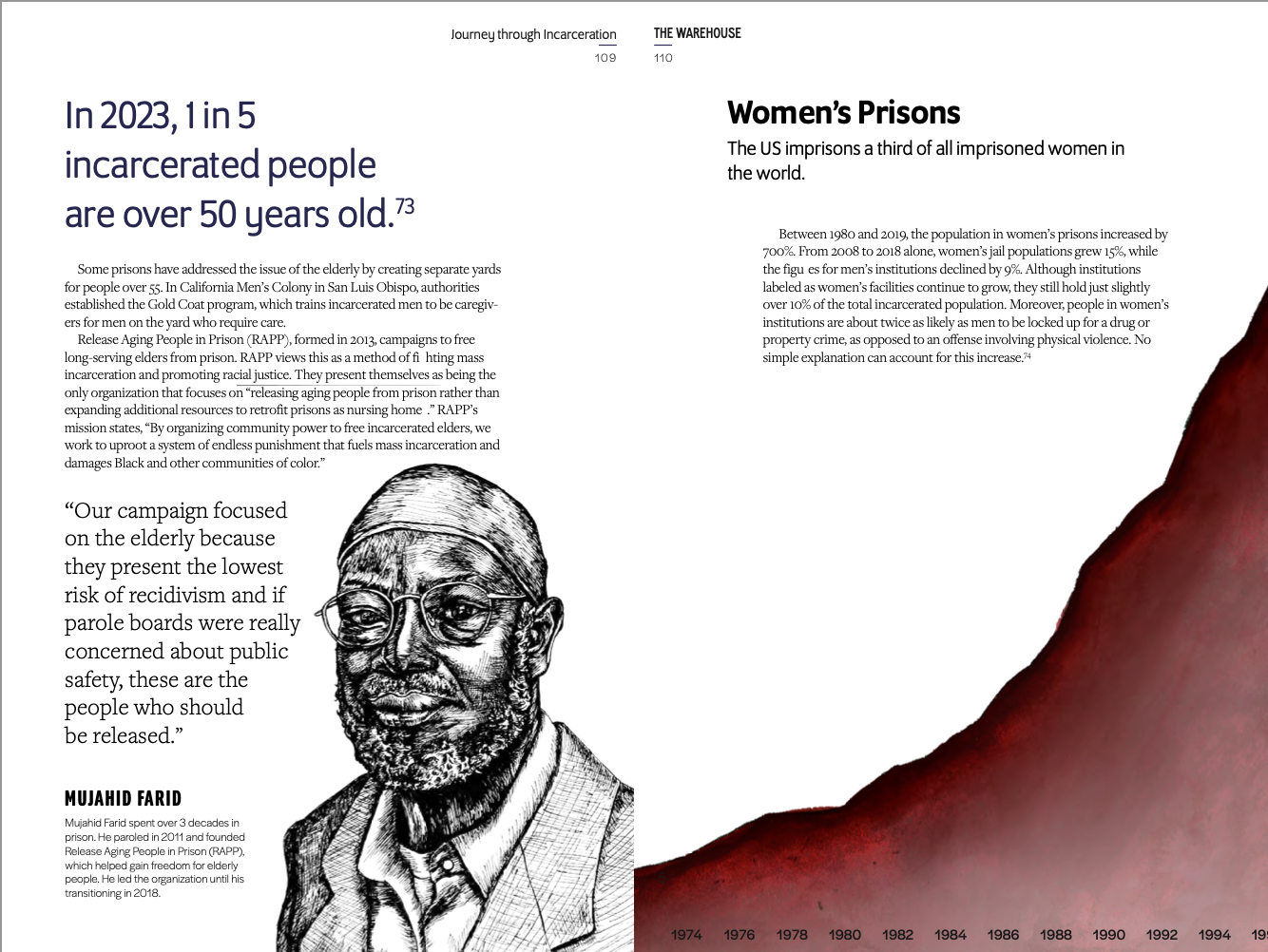

In 2023, 1 in 5 incarcerated people are over 50 years old.

Some prisons have addressed the issue of the elderly by creating separate yards for people over 55. In California Men’s Colony in San Luis Obispo, authorities established the Gold Coat program, which trains incarcerated men to be caregivers for men on the yard who require care.

Release Aging People in Prison (RAPP), formed in 2013, campaigns to free long-serving elders from prison. RAPP views this as a method of fighting mass incarceration and promoting racial justice. They present themselves as being the only organization that focuses on “releasing aging people from prison rather than expanding additional resources to retrofit prisons as nursing home.” RAPP’s mission states, “By organizing community power to free incarcerated elders, we work to uproot a system of endless punishment that fuels mass incarceration and damages Black and other communities of color.”

“Our campaign focused on the elderly because they present the lowest risk of recidivism and if parole boards were really concerned about public safety, these are the people who should be released.”

-MUJAHID FARID

Mujahid Farid spent over 3 decades in prison. He was paroled in 2011 and founded Release Aging People in Prison (RAPP), which helped gain freedom for elderly people. He led the organization until his transitioning in 2018.

Women’s Prisons

The US imprisons a third of all imprisoned women in the world.

Between 1980 and 2019, the population in women’s prisons increased by 700%. From 2008 to 2018 alone, women’s jail populations grew 15%, while the figures for men’s institutions declined by 9%. Although institutions labeled as women’s facilities continue to grow, they still hold just slightly over 10% of the total incarcerated population. Moreover, people in women’s institutions are about twice as likely as men to be locked up for a drug or property crime, as opposed to an offense involving physical violence. No simple explanation can account for this increase.

Who is incarcerated in women’s prisons?

In addition, people incarcerated in women’s prisons tend to have less serious charges than men. This means a much larger percentage of women are held in jails while awaiting trial as compared to men, the majority of whom are in state prisons. Even relatively minor charges that lead to a short jail stay can have a major impact on people in women’s jails, who are more likely than men to have childcare and other family responsibilities.

People often enter a women’s jail in an even more precarious situation than their male counterparts. They typically have lower incomes and are therefore less likely to be released on bail. Black women especially are targets for incarceration. At the turn of the century, statistics showed Black women were incarcerated at 6 times the rate of white women. By 2020, this ratio had fallen to 1.7 to 1.

Moreover, about a third of women admitted to jail have some form of serious mental illness, more than twice the rate of men. Much of this may be related to physical and sexual abuse, which an Illinois report showed was part of the life experience of at least 75% of women who entered prison. Incarceration is likely to exacerbate the trauma underlying that mental illness.

Crucially, around 80% of those held in women’s prisons are mothers, and most are primary caretakers of children. Their mental state can have ripple effects on children and other people for whom women have caregiving responsibilities.

There are particular ways in which mass incarceration impacts individuals held in women’s institutions. One report noted that 2/3 of reported sexual assaults by prison staff on the incarcerated come from women’s prisons. The report noted that people in women’s jails are more likely to leave having experienced additional harm, placing them back into the community in a situation in which they are more likely to end up back behind bars.

Several researchers have noted that prison and jail staff issue far more disciplinary “shots” against women than they do against men. These disciplinary actions often lead to the imposition of punishments like elimination of visits or phone calls, which are important lifelines for mothers and caregivers to children. A California study concluded that women got twice as many disciplinary write-ups as men for “disrespect.”

Provisions given to prison populations are often male-biased. For example, many prison or jail commissaries do not sell sanitary pads, grooming products, or any types of cosmetics. Medical services often overlook reproductive health needs or the special needs of people who may be pregnant.

Menstruation in Prison

Menstrual supplies in prison are frequently inaccessible, of poor quality, and withheld as a form of oppression and degradation. Because of the lack of supply as well as the poor quality of the pads, people often reuse pads past the point of medical safety or efficacy.

- In one jail in Michigan, people were regularly denied access to the products and were forced to rewear bloodied clothing for up to a full week. In one case, prison staff ordered 30 people to share a pack of 12 pads.

- The menstrual products for sale in prison commissaries are unaffordable for most incarcerated people. For example, while incarcerated people in Florida earn on average less than 50 cents every hour, tampons cost $4 for 4 tampons. In Colorado, a box of tampons can cost about 2 weeks of wages.

- Most facilities require incarcerated people to ask the correctional officers for menstrual supplies, resulting in an immense power imbalance. In Rikers Island jail, a prisoner reported that a guard once “threw a bag of tampons into the air and watched as inmates dived to the ground to retrieve them, because they did not know when they would next be able to get tampons.”

- The US Department of Justice investigation into the Julia Tutwiler Prison for Women reported that correctional staff regularly withheld menstrual supplies in order to coerce prisoners into sex. The report stated that “prisoners are compelled to submit to unlawful sexual advances to either obtain necessities, such as feminine hygiene products and laundry service, or to avoid punishment.

Giving Birth in Prison

Taisie Baldwin gave birth to her daughter, Elaine, while she was in prison. According to prison policy, a mother could only keep her baby for 24 hours before it would be taken away.

“My perfect baby was born on June 25, 1998, after seventy-two hours of labor... then they took me to a room on another floor. The guards were sitting next to my bed but they hadn’t cuffed me yet. And then the nurse brought my baby back... The nurse had taken a few snapshots... and she gave them to me. I was so happy I had the pictures. I knew I couldn’t take my baby with me so it was the best I could have....

“The nurse took the baby while I went to get searched; after that she gave her back to me. By then I was sobbing and begging the guards, ‘Please give me another minute.’ But they kept saying, ‘We have to leave, Baldwin.’ I took a breath and gave the baby back to the nurse.... For all I’d been through, leaving my baby at the hospital was the most painful thing I’d felt in my life...."

“When I got in the van, one of the guards had to sit in the back with me. She told me, ‘If you wanted to have children, you would have stayed out of prison.’ I wanted to hurt her so badly but there was nothing I could do.”

Being LGBTQ+ in Prison

People who self-identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or other gender-nonconforming identities (+) are often ignored in analyses of prison populations. Unbelievably, the most recent survey of this population took place in 2012. The survey concluded that 1 in 3 people in women’s prisons identify as LGBTQ+. In men’s prisons, 1 in 20 people identify as LGBTQ+. Nearly half of all Black trans people have experienced incarceration.

Several factors contribute to the criminalization of LGBTQ+ people, including: police bias, anti-trans laws, anti-LGBTQ attitudes, the failure of schools to offer safe space for LGBTQ+ students, and discrimination in setting bail. Some activists label these practices as a “discrimination-to-incarceration pipeline” that channels LGBTQ+ people into disproportionate levels of imprisonment, particularly among youth. Twenty percent of those in the juvenile legal system are LGBTQ+.

Many facilities respond to harassment and assault of LGBTQ+ people by placing those who have been harmed in solitary confinement, allegedly for their protection, but usually to the great detriment of their mental health.

Transgender people often require special hormone therapy or gender-affirming surgery. However, to receive these therapies requires an examination, which is usually denied. A survey by Black and Pink, an abolitionist organization that provides service and support to incarcerated LGBTQ+ folks, found that only 1 in 5 incarcerated LGBTQ+ people had access to underwear and cosmetics that matched their gender identity.

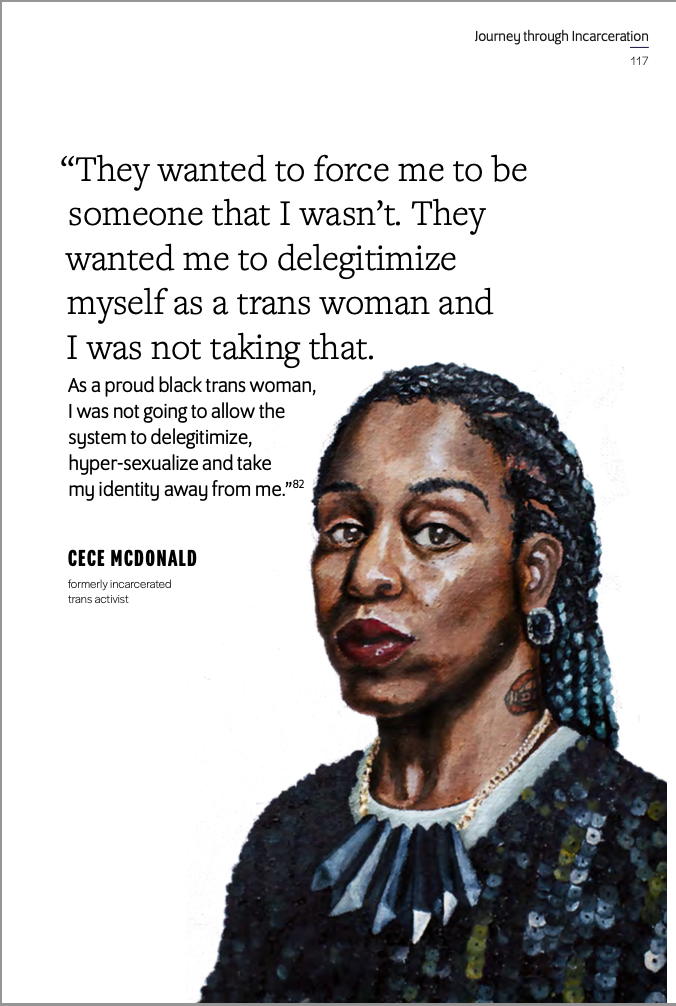

In 2013, CeCe McDonald, a Black transgender woman, killed a man who was harassing and threatening her and her friends outside a bar in Minneapolis. Originally charged with manslaughter, authorities reduced the charges to second-degree manslaughter. McDonald plead guilty and served 19 months in a men’s prison. Upon her release, she became a high-profile activist campaigning for the rights of transgender people and for reforms of the criminal legal system, including the right of an incarcerated person to define their gender.

Life as a trans person in prison is difficult and often traumatic.

The high incarceration rate of transgender people is directly related to the criminalization of survival activities. According to the Black and Pink survey, 1 in 5 transgender people had participated in the underground economy, including sex work and drug sales. Nine out of 10 of those who did sex work reported high levels of police harassment, sexual assault, or mistreatment by the police. Encounters with the police frequently led to conflict over gender identity, a conflict that persisted inside the prison.

About 1 in 10 trans people experience sexual assault from staff.

Almost a quarter of those reported sexual assault occurring 8 times or more. Nearly 1 in 5 trans people who were incarcerated had experienced physical assault from staff 8 or more times in the past year.

Other individuals among the incarcerated population also carried out verbal and sexual assaults against transgender people. Trans folks were 9 to 10 times more likely to experience sexual assault from other incarcerated individuals than the general population in the facility.

Transgender people in immigration detention facilities experienced similar rates of assault by staff and other incarcerated individuals, with 23% having survived sexual or physical assault while being locked up.

About 1 in 20 people in prison identify as trans.

Disability and Prison

People in prison are 3x more likely than people outside of prison to have at least one disability.

People categorized as disabled are disproportionately incarcerated. For example, nearly 4 in 10 state prisoners and 3 in 10 federal prisoners reported having a disability; 50% of female state prisoners and 39% of male state prisoners reported having a disability. The Bureau of Justice Statistics reported that fully 1 in 5 people in prison have a serious mental illness.

The high rate of incarceration of people with disabilities is largely a result of the closure of facilities that previously housed people with mental health issues. In 1955, state mental health institutions held 559,000 people in the US—roughly the same population as prisons. By 2000, it had fallen to less than 100,000—about 7% of the prison population at that time.

These problems are particularly evident in jails, which typically have even fewer services than prisons. According to research by the Oregon Criminal Justice Commission, “Jails have become the default case management system for repeat, low-level offenders who are often houseless, often have substance abuse disorders, and often have mental health issues, traumatic brain injuries, or other chronic health issues.”

People with disabilities are subject to greater abuse and mistreatment in prison.

A report by the Center for American Progress noted that in 4 out of 12 of the California prisons studied, 84 to 94% of all incidents of state use of force were directed towards inmates with cognitive disabilities.

In Colorado, individuals with cognitive disabilities were 10 times more likely to have the state use force against them than those without. Incarcerated individuals with cognitive disabilities also experience a higher prevalence of sexual assault.

And the impact of incarceration on mental health can be long term. As a team of psychiatrists from the University of Pennsylvania concluded, “Incarceration is related to subsequent mood disorders, related to feeling ‘down,’ including major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and dysthymia. These disorders, in turn, are strongly related to disability, more strongly than substance abuse disorders and impulse control disorders.”

People with disabilities are denied accommodations in prison and jail.

Many prisons implement the dehumanizing practice of placing people with disabilities in solitary confinement, simply because they have no idea what to do with them.

1. Lack of screening, academic accommodations, or social accommodations for people with cognitive disabilities or who are neurodivergent

The lack of screening or up-to-date screening of people arriving in prison with cognitive disabilities means that many people, especially people of color, go undiagnosed, and therefore do not receive the accommodations they need. Furthermore, there is a lack of social or academic accommodations for neurodivergent people, which often leads to social exploitation, higher rates of sexual abuse, much higher rates of violence from prison guards, and a lack of access to programs that could reduce their time. This is painfully represented in the education requirements for release or parole.

- 25% of state prisoners reported a cognitive disability;

- 12% reported an ambulatory disability;

- 12% reported a vision disability;

- 10% reported a hearing disability

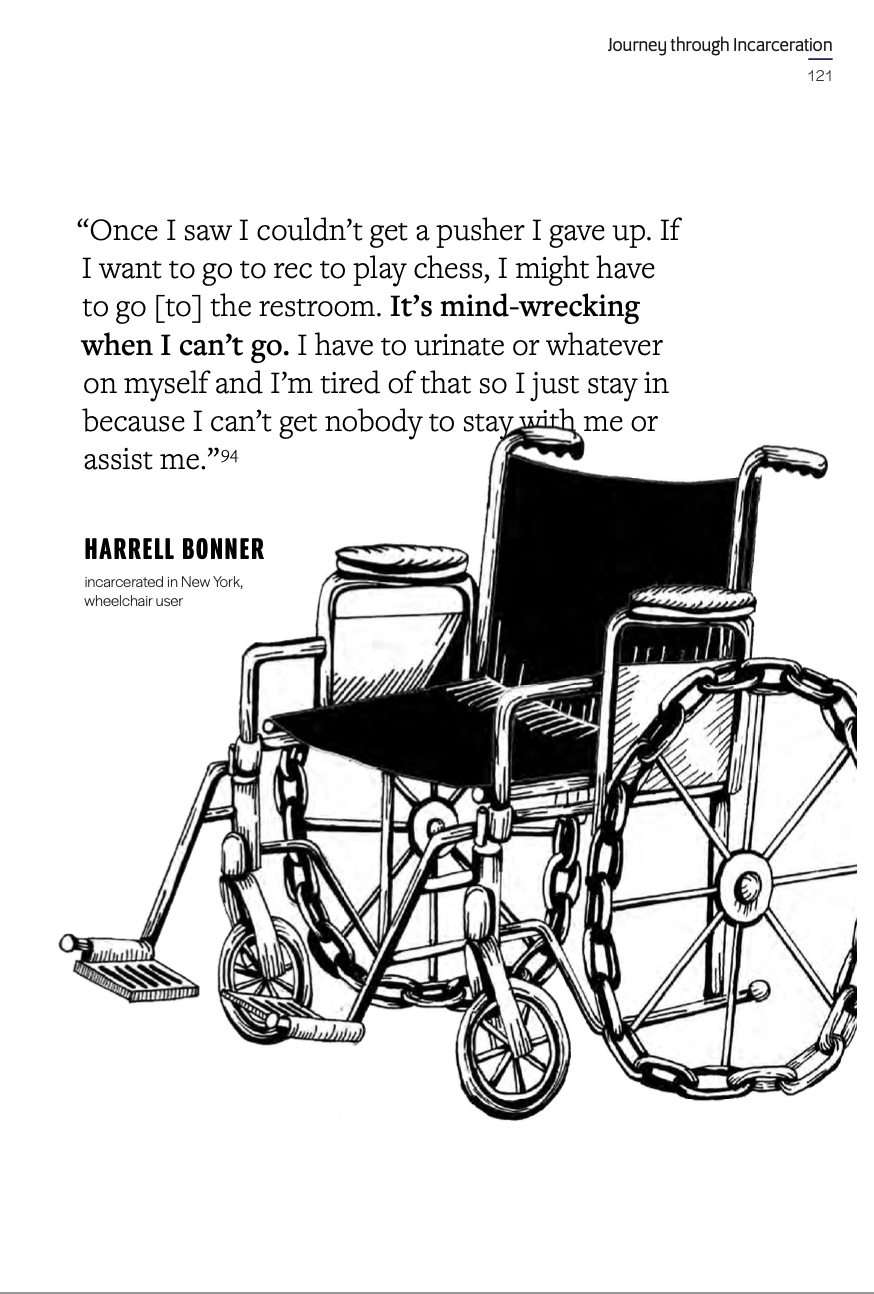

2. Lack of wheelchairs or wheelchair accessibility, crutches, walkers, or canes

The lack of wheelchairs or wheelchair accessibility for people who are wheelchair dependent is inhumane. Robert Dinkins reported that when he was in solitary confinement, his wheelchair was confiscated, forcing him to crawl around on the ground.

3. Lack of hearing aids, videophones, or sign language interpreters

Prisons often lack videophones, which are the most commonly used technology for deaf people to call each other. The existing technology in prisons tends to be either broken or unusable, leaving deaf people cut off from their family and friends. The lack of availability of hearing aids or sign language interpreters means that incarcerated people who are hard of hearing or deaf can become extremely isolated and unable to access programs, and sometimes they are even punished for their inability to obey orders they cannot hear.

The Warehouse: A Visual Primer on Mass Incarceration is available via PM Press.